“The Wire” Complicates the World of Cop Dramas

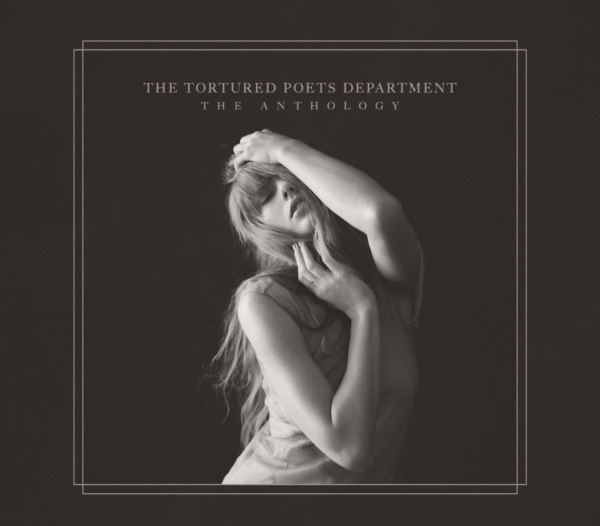

Over the past two decades, the quality of television has exploded, allowing creators to tell complex narratives over several seasons. Nowhere is this better exemplified, however, than in “The Wire.” (courtesy of Twitter)

In 2001, former Baltimore Sun reporter David Simon was fed up with the system.

Simon spent most of the 15 years he worked as a reporter covering the crime beat. In 1988, he shadowed the homicide unit of the Baltimore Police Department for an entire year and wrote a book about the experience, detailing the real process behind attempting to solve murders in one of the homicide capitals of the country. In 1993, he spent the year on the other side of the street, observing a single corner in Baltimore where drugs were regularly sold. Throughout the course of the project, he became friends with a drug addict named Gary McCullough, whose subsequent death emotionally devastated Simon.

In 1995, frustrated by the bureaucracy and problems that plagued the Sun, Simon left the paper to work on an NBC television adaptation of his first book entitled “Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets.” While the show did well, garnering critical acclaim, Simon came into conflict with NBC executives, many of whom were unhappy with the bleak way Simon chose to display many of the show’s issues. In 2001, he approached HBO with a new television pitch: a police show, set in Baltimore.

But not just any police show. Rather than the typical “good vs. evil” archetype that plagues so many police procedurals, Simon wanted to create a show that depicted the realities he had observed as a reporter. He wanted to show that there were bad cops and sympathetic criminals, corrupt politicians and honest drug dealers, and that society rigs the game so that the only ones who can ever win are those who refuse to play. He wanted to show Baltimore (and, by extension, the United States) as it really was.

But before he could begin, Simon needed help. To that end, he recruited his friend Ed Burns, a former Baltimore homicide detective who had worked with the FBI on an operation to bring down one of the city’s biggest drug lords. Much like Simon, Burns had gotten fed up with the bureaucracy and incompetency of the department for which he had worked, and had chosen instead to work as a public school teacher teacher at an inner-city middle school.

The two men proceeded to create what is, in my opinion, the greatest television show ever made. They called it “The Wire.”

Told over the course of five seasons, “The Wire” has often been described as more of a 60-hour long movie rather than a television show. Each season highlights a different area of Baltimore society: the police, the unions, the government, the schools and the press. It follows the path of a dozen different characters, of different backgrounds, careers and statuses, and the institutional dysfunction that often leads to problems. There are very few happy endings in “The Wire,” very few heroes, very few triumphant moments. There is only the bleak realism that Simon witnessed in his day-to-day beat. “The Wire” confronts its viewers with the complex, often unanswerable questions that plague American society and forces watchers to confront how they see the world.

Not wanting to distract from the show’s message, Simon made it a priority to hire little-known actors. The modern viewer, however, will be amazed at the number of talents who got their start on “The Wire:” everyone from Idris Elba, to Michael B. Jordan, to Aiden Gillen (Littlefinger from “Game of Thrones”), got their big break here. Cameos from real Baltimore figures (including both a former mayor, and the drug kingpin that was brought down by Burns’ investigation) are featured. The show was praised for the diversity of cast, featuring a predominantly Black group of characters, as well as having characters representing the LGBTQ+ community.

Despite never winning an Emmy (in what is surely one of the greatest awards show failures in history), the show received strong critical reviews and garnered an enormous following. Former President Barack Obama called it his favorite show, and the show has been ranked on the top ten list of best TV shows by Rolling Stone, IMDb and the Guardian.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I tried to watch what were considered some of the best dramas of all time. Over the course of the past few years, I have seen “The Sopranos,” “Game of Thrones,” “Breaking Bad,” “Mad Men” and “Better Call Saul.” Nothing, however, comes close to “The Wire.” It is television on a different level entirely: what Shakespeare is to the stage, Simon is to the small screen.

Over the past two decades, the quality of television has exploded, allowing creators to tell complex narratives over several seasons. Nowhere is this better exemplified, however, than in “The Wire.” It’s not an easy watch; the show is dark and complex, and isn’t the show one can enjoy just by having it on in the background. But, like any great piece of art, the challenge is worth it. Watching “The Wire” doesn’t just give you the opportunity to experience one of the greatest television shows of all time, it challenges you as a person, to see the world around you in a different light.

Michael Sluck is a senior from New Jersey majoring in political science and computer science. He has been copy editing for The Fordham Ram for the entirety...