By Tim Mountain and Kevin O’Malley

Welcome to the fifth edition of “Is It Better Than Good Will Hunting?,” the weekly culture review column where Kevin O’Malley and Tim Mountain compare food, media, experiences and more against the world of art that produced Oscar-winning film Good Will Hunting.

Good Will Hunting (GWH) is a 1997 coming-of-age drama starring Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, Minnie Driver and Robin Williams. It was directed by Gus Van Sant and written by Damon and Affleck. It currently holds a 97 percent approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

This week, we compare GWH to Brutalism, a post-modernist style of architecture popular from the 1950s until the mid-1970s.

Tim: Kevin, before we start our article, I want to apologize to our devoted fans. We haven’t cooked up a single article in this first month of school.

Kevin: Well, Tim, there’s good reason for that, and it’s not you. I wouldn’t even say it’s me. I would have to chalk it up to my diagnosis of mononucleosis.

Tim: Mononucleosis? You mean the kissing disease? Why haven’t I read about that in The Ram until now?

Kevin: I would give a limb to be in the writer’s room for even five minutes to find out myself, Tim.

Tim: Maybe we should make your diagnosis public by writing “Good Will Hunting vs. Mono.”

Kevin: No, we all know how that one would end. I want a fight here. An actual challenge for our favorite flick.

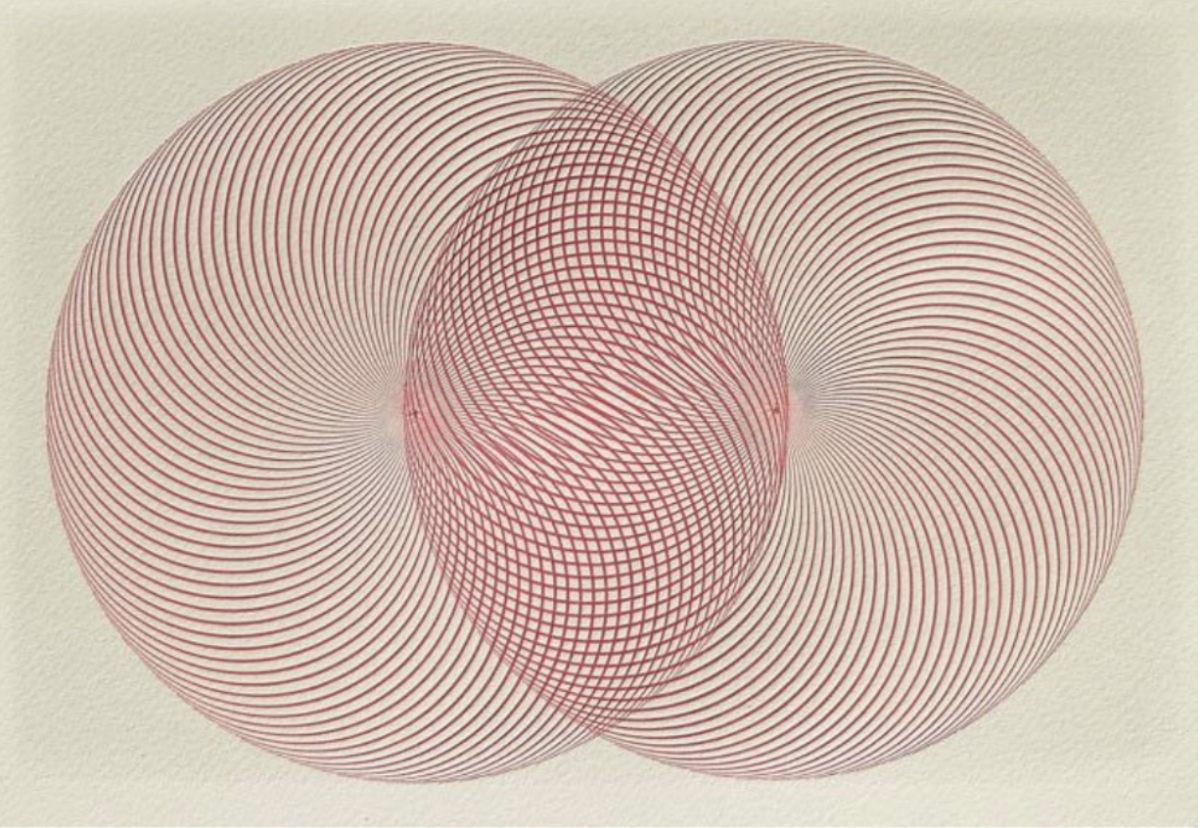

Tim: I think there are few challenges tougher than the one Brutalism presents. This mid-century architectural style is one of the most controversial since neoclassicism.

Kevin: Brutalism wrecked its way into our architectural universe by way of France (who would’a thunk) and relentlessly walled up its tall, repetitive elements of basic, functional design. And for better or worse, it has found itself a spot in popular architecture all over the U.S and U.K.

Tim: Brutalism is, like the name implies, brutal. It’s hard, tough and simple, not unlike the Boston working class. It gets the job done, it’s practical and it’s not always pretty.

Kevin: You’ve hit the mark again, Tim. The Boston working class and Brutalism are a lot like a black coffee and glazed donut from Dunkin Donuts. Its function, purpose and taste are laid right out on the table. Come and eat it.

Tim: I think there’s a good reason why Boston chose this style when erecting its city hall in 1968. We’re talking about a city that doesn’t need anything fancy. A Sam Adams lager, a lobstah roll and a swift punch to the gut are all you need to get by around here.

n, this is not unlike the movie at hand today. Good Will Hunting is too a what-you-see-is-what-you-get type of scenario. It’s Good, it stars Will Hunting and it features the helpful pro-bono work of a hard working Boston therapist.

Tim: Right you are, Kev-o. And, for all the hate Brutalism and, for that matter, Boston receives, there’s something beautiful about it. It holds promise. Both GWH and Brutalism were forged in the postmodern hellscape that was 20th-century America, but they both point at new beginnings. A new century. A new sincerity.

Kevin: Also on Brutalism: I think it’s sexy. The boldness. The intimidation. It doesn’t care what you think about it. Beautiful indeed. I think we are acting a bit like Karamo Brown here, able to find the top and shining qualities in a normally outcasted brand of structures.

Tim: You’re absolutely right, Kevin. But does this building stay standing after the hurricane that is GWH blows through?

Kevin: Let’s kick off this battle by mentioning the obvious: critical acclaim. The public absolutely hates Brutalist architecture. The story goes that when Boston City Hall was being built, the public was calling for it to be torn down before it was even finished. I don’t know about you, but I’ve never heard anybody call for GWH to be un-made.

Tim: Totally.

Kevin: I look at GWH and I feel comforted; I feel like everything is in its right place; I feel like they did a good job stacking humor and the roughness of friendship up top with the lovingness and trueness of friendship at the end. With Brutalism, I’m just not sure I’m convinced of its order.

Tim: I see what you’re getting at. Brutalism doesn’t have a narrative or a resolution. Sure, Good Will Hunting’s plot doesn’t follow the typical, linear structure that we’re used to seeing in “big-shot” Hollywood. But Brutalism doesn’t have a happy ending. It gives you reality on a rusted metal platter; “Here, this is what you get.”

Kevin: I don’t want it to seem like we’re judging on which item can “give us a happy ending,” but we are judging on the overall experience. With this, GWH just has more to offer. I’m going with the movie this time, Tim.

Tim: I agree, Kevin. This is a hard-fought battle, but at the end of the day, Brutalism just can’t keep you engaged. It doesn’t ask for the same emotional investment — an investment GWH pays dividends on. GWH surgically removes your heart, and then, when you think you’re going to have to live life without it, the movie surgically places it back in your chest. Brutalism is brutal, but it’s not that brutal.

Kevin: And if you’re going to call yourself “Brutalist Architecture,” then you BETTER be that brutal. Case closed.