“Motherless Brooklyn” Stumbles to Success

“Motherless Brooklyn” is really two movies in one. The first, a character-drama of private eyes and high-powered robbers, an assortment of colorful city-dwellers. The second, an almost documentary-like take on the political and economic life of a 1950s New York, a slight fictionalization of the famous faceoff between plucky tennis shoe-wearing old-lady activists and the authoritarian construction regime of Robert Moses and his automotive dreams.

Director Edward Norton stars in this sprawling two and a half hour adaptation of Jonathan Lethem’s 1999 novel of the same name. Norton plays Lionel Essrog, a middle-aged partner of a small private detective firm, and an orphan since age six who was taken under the wing of his current boss and the firm’s top detective, Frank Minna, played by a beefy Bruce Willis.

Lionel is a classic case of the mentally disturbed genius: he has an inhuman skill for memory and recall, his eyes and ears functioning as human security cameras, but at the price of uncontrollable physical and verbal tics and a deep-seated obsession over details. He blows out matches when lighting a cigarette until he gets the sound of the flame right and he shouts out swears and half-formed thoughts like a man with Tourette’s syndrome.

The film begins with Lionel and his partner Gil Coney (Ethan Supplee) on assignment in upper Manhattan, sitting in a car together, working on a job that Minna lined up. Norton immediately pipes in as a narrator, setting the scene for the audience: between this and some acrobatics with the adapted screenplay (written by Norton), the choicest lines from the novel are squeezed into the film, to a satisfying-if-hammy effect.

After overacting through the first five minutes to drive home the strangeness of Essrog’s broken mind, Norton gets the action rolling. Four men show up to meet with Minna, unaware of the presence of Lionel and Gil backing him up.

Minna had declined to tell his underlings anything about this latest assignment that he’d been working on, but whatever it was, things go south quick. One car-chase later and Lionel and his detective friends are left with a dead Bruce Willis and a jig-saw whodunit puzzle which Essrog, with his photographic memory, is conveniently well-equipped to solve.

This actor-directed film begins with a relentless emphasis on characterization that manifests itself clearest through a lot of put-on Brooklyn accents and angry shouting, revolving around the core of spastic Norton’s antics.

This drive continues throughout the film, partly thanks to its star-studded cast, but nevertheless cedes ground to a muddy political question that serves as the lynchpin of the initial murder mystery.

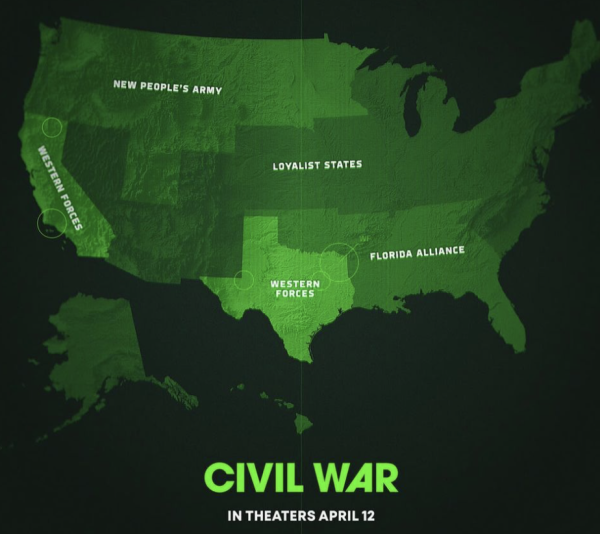

Some quick sleuthing turns Essrog and the remainder of his firm onto a cluster of activists working under a Jane Jacobs-esque Gabby Horowitz (Cherry Jones) to fight menacing Moses Randolph (Baldwin), the unelected and uncrowned shadow king of New York City construction.

Randolph’s plans, like the real life Robert Moses, involve systematically evicting lower-income and minority residents in an effort to pave the way for an automobile-friendly New York — an all-white metropolis of highways and bridges built through quasi-legal “slum renovation.”

It’s a vision of racial strife and total greed that barely exists in the movie outside of the speeches the political characters make. The racism common to the film’s 1950s setting is concentrated in the Trump-like figure of Randolph-Baldwin, giving the impression of a whole city’s worth of boiling racial hatred as product of one nasty supervillain, rather than the reality of an inherent structural inequality that enabled Moses to play God over the city’s highways in the first place. The resulting political drama thus ends up as unconvincing as it is uninteresting.

There’s a similar confusion over the time-period of the movie-image. The cinematographers equivocate between present-day and the ‘50s, in which the film is supposed to be set.

The cast dresses for their part, and the props are there, but the video itself is too glossy and realistic. The film manages a noirish sheen, but only by virtue of a jazz-choked soundtrack and copious VFX: dark mist-filled angular shots of the Brooklyn Bridge; dimly-colored drug-induced hallucinatory dreams of Essrog as he fitfully sleeps through the Long Island night.

It’s thanks to both these kind of nostalgic shots and — despite a schmaltzy love affair thrown in there at the end — the classic thrill of a detective putting the pieces together that the film ends up being pleasurable.