Fordham Professor Mark Naison Describes a Lifetime of Radical Activism

Dr. Mark Naison of Fordham University has a crucial piece of advice for his students: “You’re a much happier person if you’re working for justice.”

Born and raised in Brooklyn by two first-generation college-educated school teachers, Naison’s parents had high ambitions for him. “[They] wanted me to excel in school and go on to bigger things than were marked for other kids in the neighborhood,” he said.

Mark Naison is now a professor of African American studies at Fordham University and runs the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP), one of the largest oral history projects in the country. He is also a prominent social activist and scholar, both in New York City and nationwide.

For a young Naison, race was never an issue, he explained. He was always exposed to diverse groups. But his parents didn’t feel the same way. Naison recalled how they would switch to Yiddish when talking about race-related issues and used the Yiddish slang word “schvartzes” to describe Black people.

Later on in his life, Naison fell in love with a Black woman, something almost unheard of in the 1960s. “When I told my parents that I was in love with a Black woman, my mother threatened suicide,” he said, mirroring the exasperation he felt in that moment.

Reading became Naison’s escape from the pressures he felt from his parents. “One way I would block out the world was reading,” he said. “My parents would leave me alone when I had a book.”

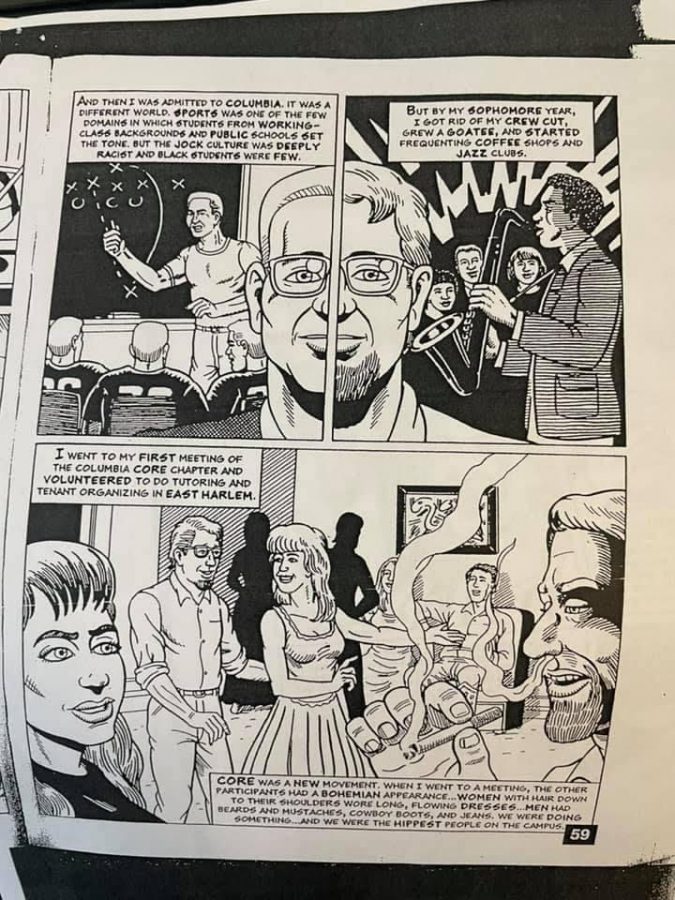

When Naison entered the undergraduate program at Columbia University, he was just a 16-year-old boy who was socially insecure and “academically, getting his ass kicked.” His college years were some of the most formative in his journey for social justice, Naison explained.

His epiphany on racism came when he read “Another Country” by James Baldwin. “It opened my eyes that being Black was a totally different experience than being white in America,” he explained. “All these Black kids I’d grown up with were going through something that they never talked to anybody about, certainly not to me.”

Naison knew he had to get involved, so he joined Columbia’s chapter of the civil rights group, CORE. His activism thrived in college, and despite growing into himself and finding his place at Columbia, his self-described tough streak from his childhood didn’t end. Naison was arrested twice and almost expelled for fighting a counter-protestor during a strike on campus.

“There were 30 seconds of this on CBS News,” he said with a chuckle. “The disciplinary officer said, ‘Mark, with that, we have to kick you out. You beat up another student on national television.’”

But Naison wouldn’t go down without a fight. He wrangled up a group of professors, teammates and fellow students to write letters to the administration on his behalf. Now, his Columbia transcript is stamped with the word “censure.”

“They created a special category for me called permanent censure, which means that I would be automatically expelled for the next violation of university rules,” he said. He then joked about his application to work at Fordham: “I don’t know if anyone has even seen my transcript.”

Naison applied to Fordham’s Afro Studies program in the early 1970s with a cover letter that began, “First of all, I’m white.” Now in his 50th year of teaching, his spirit has not been diminished.

“[He has] so much energy and passion for whatever he’s doing,” said former student Melissa Castillo Planas, GSAS ’11, recalling the many debates they had in class. “It’s a very infectious energy.”

Dr. Mark Chapman, Naison’s friend and colleague from Fordham’s African American studies department, can attest to this energy, describing how Naison leaves his office door open and plays music for the rest of the department to enjoy. “Everybody knows when they get off the elevator and hear music blasting from down the hall that Dr. Naison is in his office,” said Chapman.

As for Naison’s activism, it has only grown stronger. In addition to the BAAHP, Naison is part of the residential assistant training program for Fordham dorms and recently raised money to fund a mural at the local Boys and Girls Club.

When asked about Naison’s passion for activism, Chapman launched into a story about a campaign that Naison helped organize against a slumlord in the neighborhood where Chapman’s church is located. Naison connected Chapman’s group with other activists in the area and partook in protests and campaigns over the course of multiple years.

“It was a huge victory, and he came and did that just out of friendship,” Dr. Chapman said.

It is clear that Naison has left quite the legacy on Fordham, its students and faculty and the surrounding community. And even at age 75, Naison is still grateful for all the experiences that got him to this point. “The day I joined the civil rights group at Columbia and started working against discrimination is the day my life opened up to a lot of experiences that had been closed off to me,” he said. “Every day, I wake up and say, ‘Damn, this has been a great ride.’”