Obama Portraits are Extraordinary Yet Accessible

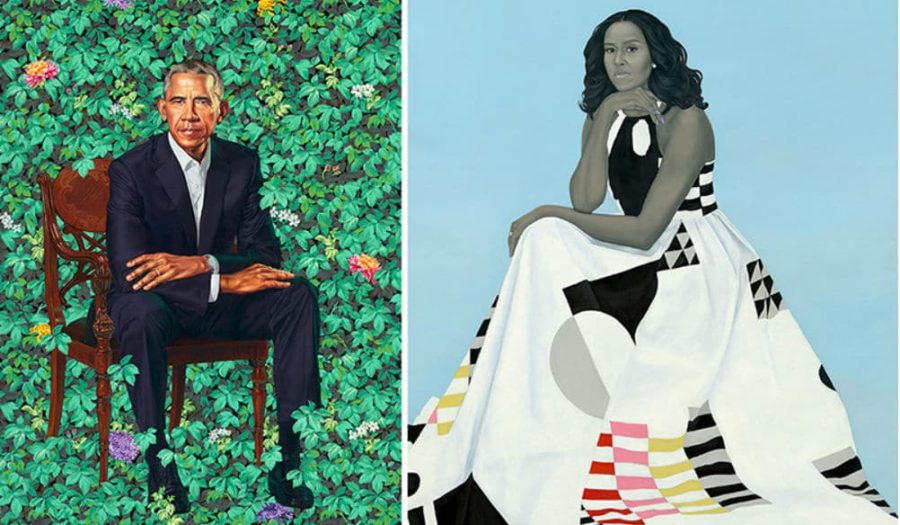

The historic Obama portraits arrived in New York City for a two month residency at the Brooklyn Museum. (Courtesy of Twitter).

Since their unveiling in 2018 at the National Portrait Gallery, the portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama have served as a destination for visitors across the country and around the globe. After donning the walls of Chicago’s Art Institute—the site of the couple’s first date—they have now made their way to New York, settling from Aug. 27 until Oct. 24 within the charming confines of the Brooklyn Museum, the second stop of a five-part tour of the country. They will travel to Los Angeles, Atlanta and Houston before returning to Washington D.C.; accessible to millions who did not have the chance to visit them previously.

Not only is the pair of portraits historic because they depict the first Black American president and first lady, but the artists themselves—Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald—are the first African Americans to be commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery to create any official presidential portrait.

According to the exhibit’s walls, Wiley, the New York-based portraitist of the former president, is known for depicting “everyday Black sitters.” This mimics the subjects of traditional paintings in Europe, made to look grand, bold, and valiant. In a short clip on display, Wiley states that he “paints the powerless,” glorifying his subjects like heroes while simultaneously underlining the fact that “Brown and Black people have been written out of mainstream history.”

“I was always struck,” the former president said in an interview regarding Wiley, “by the degree to which [the portraits] challenged our conventional rules of power and privilege.” The latest presidential portrait does just that. While Wiley depicts Obama as the powerful and influential man he is, he slouches forward in his chair, his wedding ring is on full display and he abandons a tie. Two of the buttons on his shirt are even undone. He is approachable and compassionate, but it is also clear he holds great accomplishments. Wiley’s expertise highlights that, even in art, the former president is a man of the people.

Obama is engulfed in a backdrop of lush foliage. The colorful flowers behind him symbolize different aspects of his background, subtly telling a story of his life. The white jasmine references Hawai’i, Obama’s birthplace and childhood home; the African blue lilies are an homage to his Kenyan father, who died when he was 21 years old; and the bright chrysanthemums are the official flower of Chicago, the city where his political career commenced, as well as where he met Michelle.

Sherald, the artist chosen for Michelle, is known for painting Black subjects from her community. Her work is usually done on solid backgrounds in order to accentuate the subjects. Sherald paints skin tones in greyscale, inspired by historic black and white photographs, which, according to the Art Institute, she remembers as the first time she had seen Black Americans highly represented in art. Upon their first meeting, the former first lady immediately knew that she wanted Sherald to complete her portrait.

“There was an instant connection,” she said during an interview on display at the exhibit, “that kind of sister-girl connection,” a bond that lasted throughout the entire process.

Michelle’s portrait is drastically different from her husband’s but is just as powerful. She is placed on a solid pale blue backdrop, sitting confidently with a hand thoughtfully beneath her chin. The lower portion of the painting is filled by the skirt of her dress, abstract and geometrically patterned, mimicking the quiltmaking traditions belonging to Black women in Gee’s Bend, AL. Her wedding ring, just like her husband’s, is also visible to the viewer. The billowing folds of the dress, delicate pose and soothing tones depict the former first lady as a political Aphrodite, making clear that femininity is no barrier for American influence.

“We see our best selves in her,” Sherald claimed. It is clear she is someone “women can relate to—no matter what shape, size, race or color.”

It is necessary for young boys and girls, specifically young boys and girls of color, to be able to gaze at the walls of a museum and see somebody who looks like them, which is exactly what the tour of these portraits—portraits that so beautifully depict Black excellence—allows, opening the door for so many young people to behold. “One visit, one performance, one touch” Michelle observed, “and who knows how you could spark a child’s imagination.”