The French Dispatch Charms, Despite its Heavy Handed Romanticization

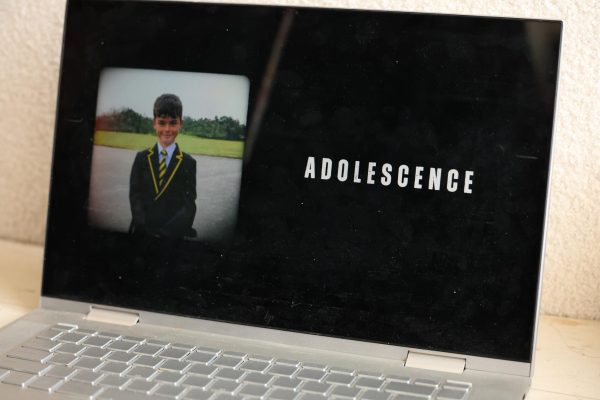

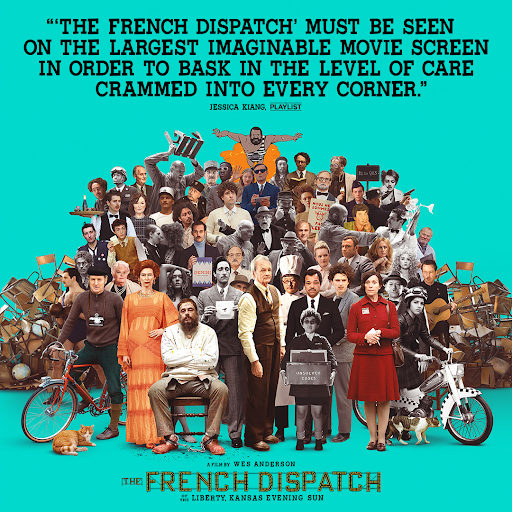

Wes Anderson’s latest film “The French Dispatch” features a host of familiar faces, all of whom lend vibrancy to his carefully crafted art film. (courtesy of Twitter)

Walking into the Lincoln Center AMC on Saturday Night — the day after acclaimed art house filmmaker Wes Anderson’s “The French Dispatch” was released to theaters — something funny catches my eye. As per usual, the theater is packed with fans of the unique director’s aesthetic: hipster undergrads with wire rimmed glasses mingle with the older, seasoned film aficionados; there are visual art students, there are laid-back literature professors; a woman in a red beret takes her seat beside me. All seems normal.

I notice, however, a strange — though not unwelcome — addition amid the room of “wes-heads”: all sorts of moviegoers, action flick fans, and teens excited about “Dispatch” star Timothee Chalamet populate the well intentioned gaggle of “Grand Budapest Hotel” and “Moonrise Kingdom” fans.

It is perhaps the uniting of the art-house film collective with casual action-comedy fans that stands out as the largest achievement of Anderson’s 10th film, which raked in a record $1.3 million dollars over its opening weekend. His films, most of which have featured the same star-studded cast (Bill Murray, Owen Wilson and Tilda Swinton are regulars by this point) and pastel-paletted, meticulously shot scenes, have finally broken out into the mainstream — at least, the most mainstream an anthology film about the final production of a Kansas-born France-based newspaper can get.

If that sounds like a lot, that’s because it is. The French Dispatch (full name “The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun”) takes the form of four vignettes, each representing one of the paper’s cherished articles. The first is a tour of the French town the movie is set in, “Ennui-sur-Blase” (definitely tongue-in-cheek, definitely fictional), led by Owen Wilson. The second is the tale of an unhinged, insane asylum artist, played by Benicio del Toro and narrated by Tilda Swinton, and his relationship with his guard (Lea Seydoucx). The third encompasses a Dispatch journalist’s (Frances McDormand) coverage and subsequent affair with a young French revolutionary (Timothee Chalamet). The fourth and last installment follows a journalist’s (Jeffrey Wright) dinner night with a famous police chief, which is interrupted with a kidnapping and a chase around town.

The four sections, different as they are from one another in content, are expertly tied together through Anderson’s heavy-handed filmmaking approach. All the telltale signs of a Wes Anderson film are present: huge, vibrant set pieces; center frame monologues; dolly shots that follow a character through a hallway or across a street; hilarious and extremely dense narration about scandals and the inner workings of a fictional town; on-screen text; cardboard cutout miniatures and melodramatic orchestral songs about rain and unrequited love.

Anderson even provides new visual techniques, relatively original filmmaking choices that blur genre boundaries. The movie contains several comic-book animation sections, for example. Portions of the movie in black and white don’t limit themselves to era or even scene, switching between noir and neon lit faces several times within the span of a conversation. Even after decades of filmmaking, Anderson’s mise-en-scene remains impeccable. He strays close to repetition during some moments, but overcomes it by adding fresh elements to the film just when the viewer thinks they might have seen it all before.

However, beyond the visual aesthetic lies the core of Wes Anderson’s filmmaking. His films — this one especially — contain a clear and unbridled idealism. His French town of Ennui, though fake, is buzzing with stray cats and cheeky choirboys; its streets twist and turn, the traffic frenetic and boutique; coffee and pastries are carefully arranged on a gleaming platter, carried smugly and surreptitiously up a flight of stairs. It is not French, but it feels French, and it is supposed to be French, even though it also isn’t.

Similarly, his conceptions of journalism skew towards earnestness, and even when satirized are satirized with a soft touch. Wright, McDormand and Chalamet wax poetic about journalistic integrity; Murray and the other editors scrutinize each dangling modifier, scraping redundant sentences off the page. In other words, and at the risk of repeating myself: it is journalism, but also isn’t.

It’s clear Anderson means for “The French Dispatch” to quite literally be an ode to France and newspaper dispatches. A careful, loving ode at that. He intends for the message and the subject of his film to be true to nature, even if the settings and characters aren’t. Despite this, the message and subject don’t connect with reality.

Many critics see this overt and maladroit romanticization as a setback. They argue the tribute borders on starry-eyed and generalizing, a misleading and naive approach to filmmaking. New York Times writer A. O. Scott accurately states that for a film about the supposed best work of a group of journalists, the movie certainly disregards “humbly dressed reporters heroically [taking] on power, injustice and corruption” in favor of a light-hearted story about travel diaries and culinary reviews gone wrong.

I’m not sure where I stand in regards to Wes Anderson’s delicately layered film, which draws so much from so much — whether that be film, literary works or small-town drama. A film of this scale, which contains more split-screened content than a standard how-to Youtube video, deserves to be rewatched multiple times. Not in a “TENET” way, where I can’t wrap my mind around how the work of art was accomplished, but in a, “The French Dispatch” way, where I want to appreciate what was accomplished.

However, there is value in having art in which we can find inspiration and look up to, even if it feels too good to be true. An escape to a serene and charming European town, in which enthusiastic writers dine on riverbanks and art dealers shake hands post-fistfight, is certainly idealized. But it also sounds like exactly that: an escape. Something to seek out, enjoy for a while, and return from. So, while Anderson’s film might be somewhat idealized and naive in its execution, there is no doubt it is a spectacle and, to put it plainly, is nice while it lasts.

Hanif Amanullah is a junior from Austin, Tex., majoring in international studies, whose passion for news writing and multimedia led him to the Ram. Hanif...