The Passing of Dean Tyler Stovall

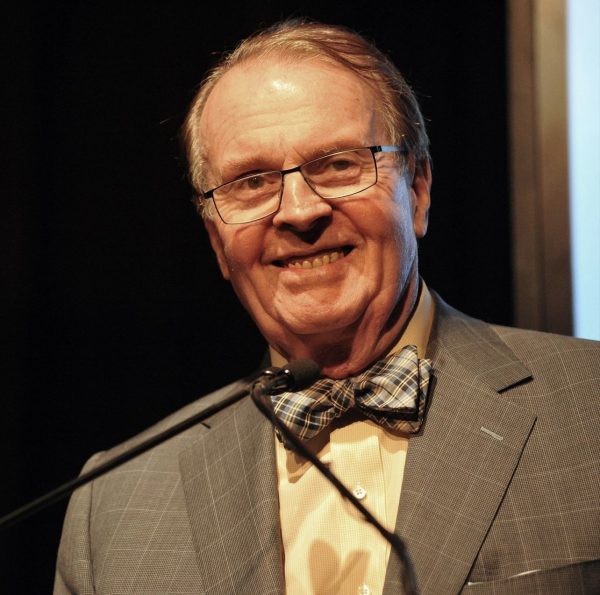

Tyler Stovall, Ph.D., was serving as dean of Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

On Dec. 10, the Fordham community suffered the unexpected loss of Tyler Stovall, Ph.D. When he passed, Stovall was serving as dean of Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS). Stovall joined the Fordham community during the fall semester of 2020.

“Dean Stovall started at Fordham in the fall of 2020, which meant that he had the incredibly difficult task of getting to know this community in the midst of the pandemic,” said interim Dean of Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Patrick Hornbeck.

Entering the Fordham community when the world was dealing with COVID-19 and dealing with the first semester back on campus came with its own sets of challenges.

“[Stovall] came to GSAS in the throes of the pandemic and immediately focused on student needs, particularly working on funding opportunities for students who were experiencing food insecurity and income scarcity during this very difficult time,” said Joanne Schwind, assistant dean of the office of academic programs and support in GSAS.

Stovall was born in Gallipolis, Ohio, in 1954. He studied history at Harvard University. After Harvard, Stovall eventually received his graduate degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. There he became interested in European history. Stovall had a particular interest in France and French studies. After receiving his graduate degree, he traveled to France to work in the Paris suburbs. There, he spent his time working with the community and turning what was once a disgruntled community whose issues felt ignored into a flourishing electoral base. Stovall eventually went on to earn his Ph.D. in French and European history in 1984. Stovall was primarily a French historian; however, he also worked in education, administration and became an author.

Stovall wrote six books in his lifetime. His first book, “The Rise of the Paris Red Belt,” was published in 1990. It came from his time working in the Parisian suburbs. The book was a revised version of his dissertation, “The Urbanization of Bobigny,” written in 1984.

Throughout his career, Stovall was an educator. He taught Université de Polynésie Française in Tahiti, Ohio State University and UC Berkeley. Stovall served as dean of humanities at UC Santa Cruz for six years before eventually coming to Fordham.

One of the hallmarks of Stovall’s character was his ability and priority to see people for who they truly were. This was expressed through how he treated those around him and his continued work and advocacy for diversity, antiracism and inclusion.

“His own background and his own academic interests led him to prioritize anti-racism, diversity, equity and inclusion. And to do so not just on the level of how we take care of each other, which is obviously super important, but also thinking about what social, political and cultural forces that led to systems of exclusion and marginalization,” said Hornbeck.

Stovall’s final book, “White Freedom,” came out just before his death. The book looks at how the Western idea of freedom — specifically those of the U.S. and France — only embodies freedom for white people. Stovall’s career focus on equity seemed to translate into how he interacted with his colleagues and students. He was passionate about getting to know students and connecting to them on a deeper level through both his life experiences and learning things about them.

“My observations were that Tyler related to other graduate students using the lens he developed during his own training. A native of Gallipolis, Ohio, he knew what it meant to be a minority in graduate school and in less-inclusive circles, which afforded him an empathetic ear,” said Marc Arteaga, GSAS ’23, vice president of the graduate student government.

Arteaga said he thought of Stovall as a mentor. While he did not get to know Stovall’s capacity as a scholar, Arteaga developed a relationship with him through personal dialogues.

“I will share the last lesson he imparted before his passing, one that speaks to truth. I mentioned to him about a large degree of anxiety that I suffer from and, in a way to assuage my fears, reflected on the way he felt as he stared down the barrel of the latter half of his own twenties. ‘Most importantly,’ he said, ‘you have to understand what your convictions and beliefs are in moving forward. Only then can you discern between the choices you will be faced with,’” said Arteaga.

Arteaga said he remembers that interaction distinctly because of the profound effect it left on him. He said that this memory helps define Stovall’s mentorship style.

To his staff, Stovall also expressed interest in getting to know them as people and beyond just their job title.

Lauren Grizzaffi, director of marketing and communications at GSAS, recounted bonding with Stovall about their children. “I have a young daughter. She’s nine months old now, but early on in his tenure with us, I had to have some conversations [with Dean Stovall] of ‘I’m now pregnant,’ ‘what does my maternity leave look like,’ as well as some additional personal conversations,” said Grizzaffi.

Grizzaffi remembered that her interaction with Stovall about her child continued when she met him in person.

“The first time I physically met him, already having worked with him for over a year, we went to his office for a meeting, and he said, ‘let me start off by saying, here’s my baby.’ He [showed me] a picture of his son, who I know is in college now. It was a double-sided picture of his son when he [was about] four years old, and another when he was a little bit older,” said Grizzaffi. “Just the fact that he started the conversation that way was such a standout. What we had to talk about was a heavier topic, but I remember the way he started the conversation from the meeting, not the stuff that I had to share or what I needed to inform him about.”

Hornbeck also shared that Stovall was passionate about interacting with people and getting to know them. “At first, I got to know Dean Stovall through Zoom; he was in a number of meetings I was in. At that time, I was working part-time in the Provost Office in addition to teaching, and so we would see each other with some regularity through these meetings,” said Hornbeck. “What I remember of him is that he had a really infectious smile. He had a deep excitement for wanting to get to know the people he was getting to meet.”

Stovall’s death was unexpected. He passed the day after the GSAS holiday party. Many people recount that he was full of light and life at the party. According to Hornbeck, people have forwarded him emails that Stovall sent them the morning of his death.

“At the holiday party, people told me that they had seen him just beaming about the fact that he and his family were about to take their son to Paris for his study abroad program, and, of course, for Dean Stovall, Paris and France, in general, was such a place that formed his imagination and formed his own understanding of himself and concepts like race and racism,” said Hornbeck.

Stovall left his legacy not just on the university but on the world through his work and influence. American author Gloria Jean Watkins, better known by her pen name, bell hooks, wrote about many social issues in the U.S. and grew to prominence in the African American community. She unfortunately passed away a few days before Stovall.

“So many people commented on Twitter to something of the effects of ‘this was a really cruel week for the Black Academy to lose both bell hooks and Tyler Stovall in the same week.’ And because bell hooks was such a world-transforming figure as well, I thought it just spoke volumes about how people thought of Dean Stovall’s work, that they were mentioned in the same sentences,” said Hornbeck.

Stovall’s memory lives on at Fordham through the people that worked closely with him, as well as his family.

“He inspired me to pursue my goals with a focus on equity and inclusion, and a vision toward the future of GSAS and its students. Even though his time with GSAS was brief, Dean Stovall’s kindness and compassion toward his colleagues, staff and students will have a long-lasting impact on us all,” said Schwind.

Grizzaffi shared those sentiments with Schwind.

“I know he was probably working on so much behind the scenes, and it seems like it just stopped, which it did. As a school, I hope in whatever way we can [carry on] his name, legacy and whatever his vision was,” said Grizzaffi. “I don’t think anyone could have a bad thing to say about him. He was just a good person, and it didn’t take long to figure that out. I wish Fordham and GSAS got to know him more and for longer.”

Isabel Danzis is a senior from Bethesda, Md. She is double majoring in journalism and digital technologies and emerging media. The Ram has been a very...