Fordham Senior Studies Rare Disease, HCM, on Fruit Flies

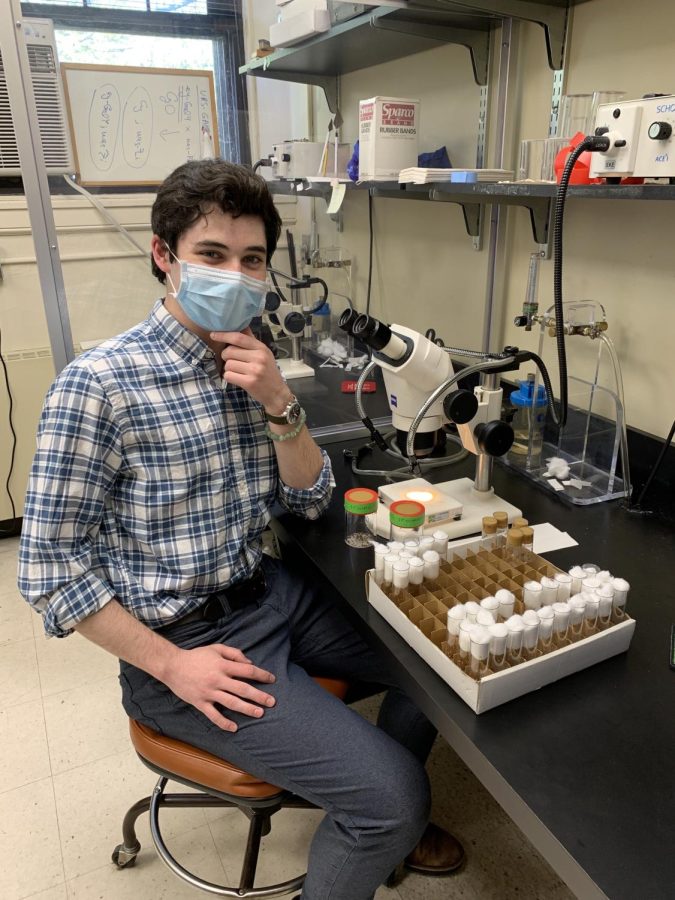

Jacob Bartz, FCRH ’22, a biology and anthropology major and bioethics and environmental studies minor, is currently participating in a genetics lab researching fruit flies. Bartz tests fruit flies to gain a better understanding of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) disease, a cardiac disease that affects 600,000-1.5 million Americans. HCM causes the heart walls to thicken, making it harder to pump blood. However, there is a rarer type of the disease that is more extreme; when found in human infants, they generally die within a year.

The lab run by Dr. Dubrovsky of Fordham’s biological sciences department, previously has incorporated the genes that cause this mutation in humans into the genome of fruit flies in order to gain more insight into the workings of the disease.

“It’s a gene that’s found in both human and flies, and so they incorporated the same mutation that causes the disease in humans into the flies, and so I study that gene and how it presents itself in the flies to look for maybe the mechanism of action of how the disease presents itself,” Bartz said.

Scientists already understand how the disease works in humans, however, there is a lack of knowledge concerning exactly how the disease is caused. “I worked with a graduate student and Dr. Dubrovsky … we found together that there are actually extra nuclei in the mutant fly heart cells,” Bartz said. After these findings came to light last spring, Bartz applied for, and ultimately received, a research grant to study how these nuclei present themselves. By using different stains, Bartz discovers that extra nuclei can be found both within a single cell and in new cells.

Following this discovery, Bartz moved on to trying to figure out when the new nuclei form during larval development. “This then led us to the question of when are we going to see DNA synthesis taking place, because that generally is a precursor to mitosis … the heart in a fruit fly is not supposed to be creating new cells; it’s supposed to have a set number,” Bartz said. Eager to learn more about this question, Bartz applied for another research grant last fall, and this is the topic that he’s been working on since.

Currently, Bartz works with a population of fruit flies, which he then breeds to get larvae. This allows him to feed the larvae a chemical that is then incorporated into their genome. “If it’s incorporated, that means that DNA synthesis is taking place, which would give us an indication of how larval development functions with the heart.” Bartz feeds the larvae this chemical at specific times for specific durations and then dissects them to look at their hearts and other organs for incorporation.

As a senior, Bartz’s goal is to pinpoint a specific time in which DNA synthesis takes place during the larval period before he graduates; he has confirmed that within the 96-hour larval period, DNA synthesis takes place, but continues to search for an exact time. There are certain limitations with the research, as the chemical Bartz feeds the flies is toxic if they are too much, and their death results in their inability to be studied.

In the future, Bartz hopes that finding the mechanisms in which the mutation functions in fruit flies will help researchers understand the human form of the disease and help target treatments for the disease in humans.

Last summer, Bartz had an internship doing clinical research with HCM patients. “It was really cool to see from a clinical perspective how they’re trying to help people that have it.”

In terms of his future, Bartz enjoyed this project and delving into the field of research. He knows that he wants to continue working in research for his career path. “It’s been really great that I’ve been able to go from basic research on fruit fly cardiology to clinical research where I’ve been able to see it in human patients with the same disease.”