The Tri-State Area Remembers 9/11 More Than Most

On my daily morning run, I pass through the Rose Hill campus garden, between Murray-Weigel and Thebaud Hall, right across from Finlay. In the madness of Fordham mornings — students going to class, getting breakfast, meeting with friends — the garden is a brief respite from the chaos, an unusually peaceful place. It is a small garden and, most mornings, it takes only a few seconds to run through.

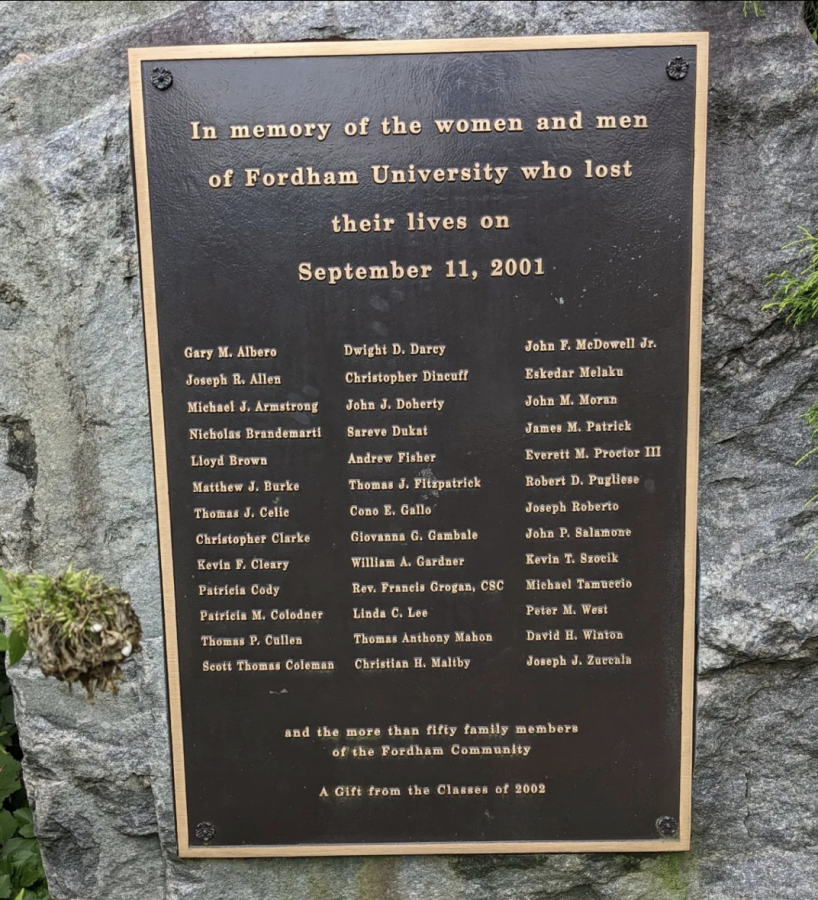

This Sunday, however, I stopped short in the garden, as is my habit every year. In the center of the green, surrounded by an array of bushes, there is a stone with 39 names written on it. On the top is a dedication: “In memory of the women and men of Fordham who lost their lives on September 11, 2001.” This dedication is something many Fordham students walk past everyday without ever sparing it a glance. To many students, especially those who come from outside the New York Metropolitan area, the significance of the stone is lost completely.

The monument isn’t an unusual sight in the Tri-State Area. Where I am from, New Jersey, my town and every town surrounding it has a similar monument somewhere. On it is a list of names of firefighters, police officers and ordinary workers. It’s a list of people who, on the morning of Sept. 11, kissed their spouses goodbye, told their children to have a good day at school and told their parents they loved them. It’s a list of people who had books they were reading, movies they were excited to see and favorite songs they couldn’t stop listening to. It’s a list of people who never came home.

I’ve talked to Fordham faculty who were present on campus on 9/11 and the chaos that followed over the ensuing weeks. Remember, this was a time before everyone had cellular devices. People were lined up for phones. The school was trying to locate students who had been working in the city and students tried to contact their parents who worked in Manhattan.

My generation — and more specifically, the class of 2024 — is the first to be born almost entirely in a post-9/11 world. We have never lived in a world where we don’t have to go through added security at airports. We have never lived in a world where the Twin Towers were a part of the New York City skyline.

I have heard that the events of Sept. 11, 2001 shattered the myth of American invincibility, the notion that no foreign group or power could cause us any real harm. The class of 2024 has never felt that unquestioned safety. The world we know is a fearful one. The black smoke that poured from the Towers still hangs over us.

One of the strange things about coming to college is encountering people who were raised in different parts of the country and realizing that things you assumed were a part of the universal experience are actually quite unique to your town, state or region. In New Jersey, 9/11 is always a solemn day in schools. There is a moment of silence in the morning, and teachers tell stories about their 9/11 experiences. Everyone remembers where they were that day and what they were doing when they first heard about the attacks. Everyone knows someone who was in Manhattan that day. Almost everyone is at least one degree away from someone who perished during the attack.

I always assumed that the trauma associated with 9/11 was a national experience. Coming to Fordham University, I realized that for a lot of people in other states, 9/11 was never as big of a deal. It was a tragedy, to be sure, but one that happened far away to other people. But in the Tri-State Area, stories about 9/11 were always about us: our families, our friends, our neighbors and our city.

Unlike similar traumatic moments, such as Pearl Harbor or the Kennedy assassination, the national trauma of 9/11 has become more complex and politicized over the past two decades. It is difficult to talk about 9/11 without also mentioning in the same breath the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the consequences of American imperialism or the Patriot Act. Mentioning 9/11 in our present atmosphere often feels more like an excuse to showcase fervent patriotism or an excuse to criticize the failures of America’s past more than it feels like a national tragedy.

Some historians say that it takes 20 years for an event to become history; if that’s the case, then 9/11 officially joined the history books last year in 2021. Much like other national tragedies, it has begun to sink into the annals of memory. Fordham’s current undergraduate students have no memory of 9/11, either because they were too young or had not yet been born. For many across the country and the world, it’s a relic of the past, something to be learned about but not mourned.

But not in the Tri-State Area. Every year, on Sept. 11, thousands of people visit the 9/11 Memorial and Museum to pay their respects and to remember the ones that were lost. For all Fordham students, if you find yourself in the city on the 11th of September next year remember that, here, we will never forget. Here, there are scars from that day that have still not healed. Take a moment, in your own way, to shut out the hustle and bustle of New York City, and remember that horrible, horrible day, and all the people who never got to come home.

On Sunday morning, I stopped in the garden and read the 39 names listed on the stone. I said a prayer. And I continued my run.

Michael Sluck, FCRH ’24, is a political science and computer science major from Verona, N.J.

Michael Sluck is a senior from New Jersey majoring in political science and computer science. He has been copy editing for The Fordham Ram for the entirety...