Fordham Sophomore Researches Women in Early Modern Colonialism

Catherine Williams, FCRH ’25, is currently working on a research article about landed class women in positions of authority as a symptom of early modern colonialism.

Williams originally came up with the idea for this research topic during this past spring semester in a course on Modern U.S. Women’s History. In July, Williams drafted the research article and sent it to a journal. She has since received corrections and hopes to get published sometime in 2023.

Williams’ article focuses specifically on the colonial southern United States and the colonial Caribbean. The purpose of the article is to use examples of landed class women in these settings to challenge the belief that all women are victims of patriarchy.

“There’s this common assumption in our society and culture that women are, always have been and always will be victims of patriarchy,” said Williams. “But it is important to understand how they overcame barriers to authority and challenged patriarchy.”

One example Williams describes is how landed class women found loopholes in patriarchal traditions.

“Primogeniture, the practice of giving everything to the oldest son, was designed to prevent women from occupying positions of authority. But women overcame those barriers because of the loose interpretations of traditionally male-dominated practices,” said Williams.

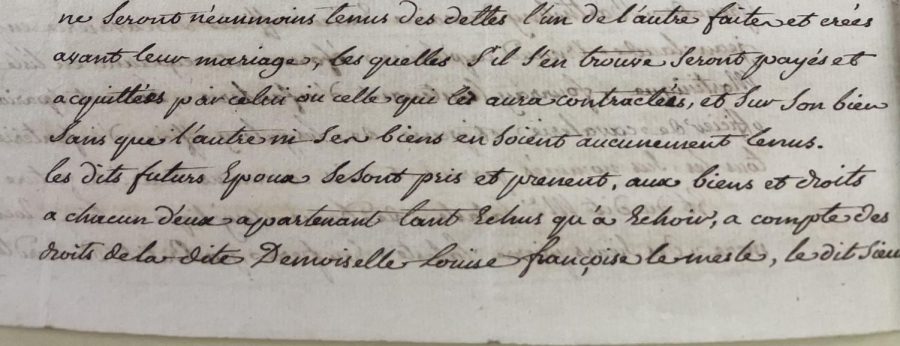

Williams uses many sources from the colonial era including runaway slave advertisements, marriage contracts and wills written by women to show how women controlled property and wealth.

“In the colonial south, a lot of landed class women placed those runaway slave advertisements, and they directly stated themselves as the planter, claiming ‘I own this plantation, bring back my property’ which definitely challenges the idea that women couldn’t own property in their name,” said Williams.

The concept of women owning property was very normal at the time, according to Williams. “In the colonial south, men were very ambivalent to women occupying positions of authority, and a lot of women even employed low class white men to do all their dirty work.”

In both sections of her research, Williams explores women’s authority in relation to marriage.

She describes how “unmarried women in the southern U.S. exercised authority as delegates, working alongside wealthy white men,” and how in the Caribbean “women made marriage contracts with strict criteria for husbands.” Williams then discusses how, in both the southern U.S. and the Caribbean, husbands and wives hold equal authority as plantation owners.

“Women subverted patriarchy to occupy and assert positions of authority on plantations. But in this day in age, women subvert patriarchy to claim agency and gain rights or regain agency and regain rights that were previously denied,” said Williams.

Williams said that she researches women of the past to better understand the obstacles women face today.

“In addition to challenging the notion that all women were victims of patriarchy, it is increasingly important to understand how women assumed their own agency when they were systemically denied from having it in the first place,” said Williams. “With recent events in the United States and in other countries with barriers to female agency, it is important to understand how women rose above pro-male institutions to claim it in the past. That way, we can learn from landed-class women in the Colonial Era so that women can reclaim their lost agency or gain agency they never had.”

Williams’ research on landed class women during early modern colonialism will help to promote forgotten female history and subsequently help women now.