Safiya Sinclair’s “Cannibal” Threatens to Swallow You Whole

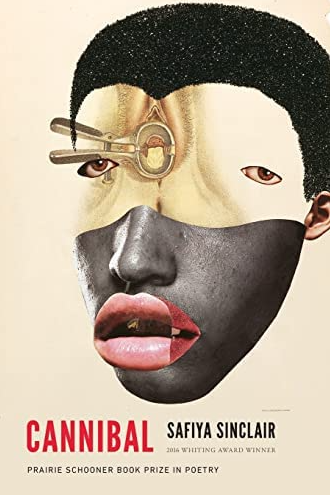

“Cannibal,” Sinclair’s debut collection, was published in 2016. (Courtesy of Twitter)

With a “wild conch-shell dialect” and “black apostrophe curled tight” on her tongue, Safiya Sinclair is a poetic Rastafarian magician — conjuring up diction that is nearly spell-like, she builds an altar in which “cannibal masters the colonial/curse.” Colliding like waves on the shores of Montego Bay, the poems in her debut collection, “Cannibal,” merge feverishness with reclamation in order to explore her Jamaican childhood, history, race relations in America, black womanhood, tenderness, otherness, emancipation and exile.

“Cannibal,” an English variant of the Spanish word “canibal,” is derived from the word “caribal” in reference to the native Carib people in the West Indies. Upon encountering the Caribs, Christopher Columbus described them as “mythical beings with the snouts of dogs” possessing the murderous appetites of “Caniba” for human flesh, a word borrowed from the Arawaks. It is from this that the word “Caribbean” originated. Thus, “by virtue of being Caribbean,” Sinclair writes, “all ‘West Indian’ people are already in a purely linguistic sense born savage.”

It is from this rich history, the trauma of the African diaspora, that Sinclair draws her inspiration. The English language will always be the language of the colonizer, whereas the page gives her a sense of belonging. Effectively, she weaponizes Columbus’ “canibal,” a misconstrued sign for the savage indigene, and turns it on its brute head. In a melodic frenzy, she consumes its sadistic roots and spits it back out as her own. Forged from Shakespeare’s antagonistic Caliban, Sinclair unsheathes the rebirthed visage of the “Monstrous” as testament to the hypocrisy, hubris and trauma that form colonial institutions of anatomical domination and emotional subjugation.

Island-born, Rasta-girl and a “dark landscape” among corn-fed strangers, Sinclair’s identity as both woman and immigrant interloper is not just a duality but a sphere — its points constantly intersecting and brushing up against one another. Carved in her own language of the macabre, her words burn with the pain of womanhood and the fury of her history. The book itself is separated into five parts, a nod to five Shakespearean acts, that map out her mission to turn the language of the colonist inside out and against the oppressor. Through epigraph, allusion and quotation — most notably “The Tempest,” Thomas Jefferson’s “Notes on the State of Virginia” and Samuel George Morton’s pseudoscientific “Crania Americana” — Sinclair creates haunting conclusions that interrogate these colonial literary brandings.

“Cannibal” is a poised Venus fly-trap, a ravishing reclamation of Eve’s image that pales both Adam and God in comparison. Wild with iambic trimeter and clusters of vowels, the prosodic elements of Sinclair’s poetry pulsate with the verdant oasis of her home. The waters, flora and fauna of Jamaica have found a home within her prose: “This place is your place, wreathed in red/Sargassum, ancient driftwood/nursed on the pensive sea.”

Poet Laureate Ada Limon, another personal favorite of mine, remarks, “With exquisite precision, Safiya Sinclair is offering us a new muscular music that is as brutal as it is beautiful. Intelligent and elemental, these poems mark the debut of a poet who is dangerously talented and desperately needed.” And beautifully so, Sinclair creates a fortress through full-blooded lyricism and fertile imagery that is absolutely necessary. She evokes a home that is no longer accessible, a body that is deemed uninhabitable and a song that is both mythic and explosive.

In “Notes On The State of Virginia, III,” she writes:

“What burns this house burns apishly/The mouth the church this immaculate body/such untouchable sounds we have made of ourselve/A blues archeology/Thus like a snake I writhe upward, mottling and spine-thick, where heavy nouns/flay through my tubercular, their heavens coil a twisted rope.”

Pulsating, lush and rich with sea-salt grit, Sinclair is a “murderess, a glowing engine timed to blow.” Her language is a refuge for those who wish for the surf to rewrite their silence. Revolting against a patriarchal postcolonial world, “Cannibal” is a creaturess that threatens to swallow you whole.

Ilaina Kim is a senior from Atlanta pursuing a major in English with a minor in philosophical studies. She joined The Fordham Ram as an Assistant Editor...