What We Can Learn From“Ragnarok”

I have always loved reading ancient mythology. When I was a child, I found my heart and soul inside of one series, Rick Riordan’s “Percy Jackson & the Olympians.” This Editor’s Pick is not about that, nor is it about the cultural mythology Riordan’s books draw on. This EP is about the world that I discovered after I exhausted the seemingly unending Greek mythology and moved on to another set of stories: Norse mythology. These myths include gods like Thor and Loki, both of whom have returned to the forefront of common knowledge through such films like “Thor: Ragnarok.” The film, as the title suggests, depicts a reimagined version of Ragnarok, the final battle that shall end the world. In the movie, Thor fulfills the prophecy of Ragnarok by inviting Surtur to Asgard, allowing him to destroy it in a last ditch attempt to defeat his malicious half-sister, Hela. Thor, Loki and the few remaining Asgardian watch on, finding hope in their community even as they watch their home fall. The original tale, however, is much more grim. A prophecy to the ancient Norse, it foretold the absolute destruction of the world — earth, the cosmos and even the gods above.

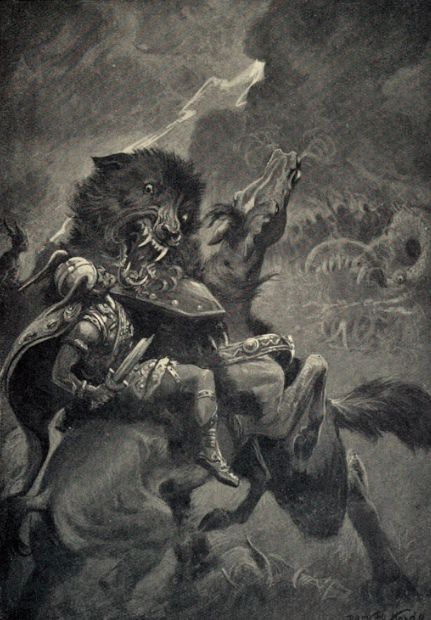

According to the myth, there will come a day when an unending winter drives humanity to madness, causing them to fight within families and destroy their communities. After this, the two wolves that have hunted the sun and moon throughout eternity shall finally succeed in their quest. Loki’s monstrous children, Fenris the wolf and Jormungand the serpent, shall break free of their imprisonment and attack Midgard, the home of humanity. Loki and the giants shall follow, marching on Asgard as they finally bring about the battle that will end the world. Heimdall, the sentry of Asgard, will alert the gods, known as the Aesir, who shall meet their foes on an impossibly large plane. Odin will lead the army of Valhalla against Fenris, but they will fail. Another god will sacrifice his life in killing Fenris. Thor will slay Jormungand, but inevitably die after succumbing to the serpent’s poison. Loki and Heimdall will kill each other. When so many of the gods and monsters have slain one another, the earth shall be swallowed up by the sea. Nothing will remain, except for a few goddesses playing chess in what remains of Asgard.

In some versions, the story stops there. However, in the one I read as a child, something comes afterward: life returns. Grass, trees and even people, Lif and Lifþrasir (“life” and “striving after life” in Old Norse). The ending is a bit on the nose, and some scholars wonder whether the invention of this happy(er) ending was due to Christianity’s introduction into the region. Regardless, this story, which ends in rebirth, captured my whimsical 11-year-old imagination and has never left it.

You see, I minor in environmental studies. So much of my college experience, and my life beforehand, revolved around nature, human apathy and the crisis that has resulted from the combination of the two. It’s bad. The effects of climate change have already destroyed people’s homes and livelihoods: in 2021, wildfires on the west coast burned so much and for so long that the smoke filled the sky in my hometown of Wilmington, Del.; in 2022, flooding from melting glaciers and unprecedented monsoon rains affected 33 million people in Pakistan; in 2023, Europe suffered a heat wave that left the tops of mountains snowless in January. Look outside, the temperature in New York City this winter barely dropped beneath thirty degrees. The Hudson used to freeze.

Climate change is the existential threat of our time, and while it probably should have been regarded as such much earlier, this truth began to grow in popularity when I was about 11. I, like many other people of Gen Z, grew up with the burden of the world on our shoulders. There were a few sayings that rang throughout my home and elementary school: “Turn the lights off, or you’ll kill a polar bear!” As if one child could prevent the massive loss of life happening around the globe by flicking off one light. It’s a hard thing, coming of age and hearing how your generation is going to watch the world die right before your eyes.

When I first read the story of Ragnarok, I found peace. In it, the whole world ends — the oceans flood the land, the monsters come unleashed and the gods die — but I found comfort in it, because life began again. It’s an interesting rejection of the Western, or at least the American, obsession with immortality. We long to have some part of our individuality continue beyond the veil of death, enabling us to remain a part of this world until the edge of eternity and then, somehow, beyond. If not our bodies, then our souls. If not our words, then our writing. If not our society, then our monuments. Something has to survive. But, ultimately, everything that we know will someday be gone. Our bodies, our language, our gods. Whether the end comes with the slow and excruciating drying of the planet’s surface or the inevitable explosion of the sun, humanity simply cannot outrun the advent of oblivion.

However, life will continue. I have no quarrel with the potentially Christianized ending of Ragnarok’s story, for life is resilient. Animals and plants took over the Chernobyl nuclear site almost immediately, there’s bacteria that can break down plastic and life itself likely began as a mess of molecules, lightning and some really hot rocks. Life will always continue, even if it doesn’t appear in a form we recognize. That’s the answer as to why this grim, awful tale of death calmed my 11-year-old heart. The sea may flood the land, the gods may die, but when the waters recede, life will return green and growing.

Kari White is a senior from the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it state of Delaware. She is majoring in English with a concentration in creative writing, as well...