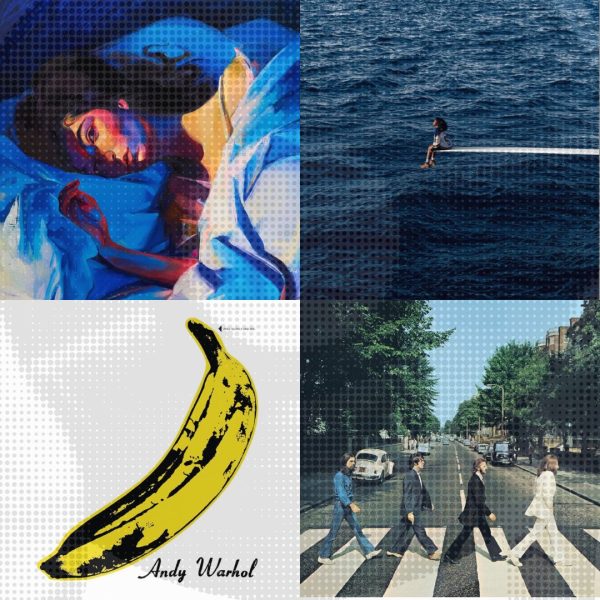

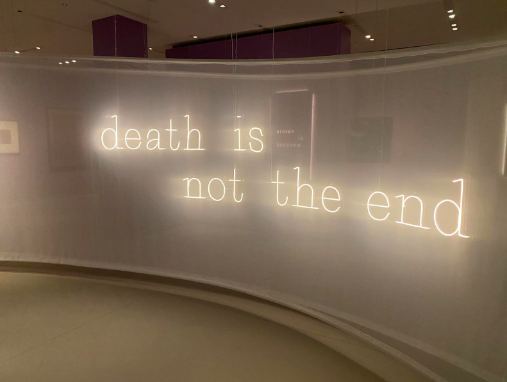

“Death is Not the End” At the Rubin Museum

The Rubin Museum, famous for its collection of Buddhist art, opens a new exhibit exploring the afterlife. (Courtesy of Clare Hannon for The Fordham Ram)

I have spent my last three years at Fordham studying history and medieval art. Not a lot about Tibetan Buddhism comes up in that field, so my recent trip to the Rubin Museum in Chelsea was a completely new experience. The museum itself is hidden and a little out of the way. I found the unassuming museum on 17th St., away from the horns and traffic of 7th Ave. and beyond some scaffolding. The Rubin Museum was founded in 2004 by Donald and Shelley Rubin, a husband-wife team. Though not as large as the Metropolitan Museum of Art or as old as the Morgan Library, the Rubin is arguably one of NYC’s most important cultural institutions, with one of the world’s largest collections of Buddhist art. The Rubin Museum reaches across current geo-political borders and shows Buddhist art from the Himalayan region, instead of any one country. Along with the artifacts permanently in the collection, the curators of the Rubin Museum work hard to make sure that the rotating exhibits are interesting and relevant. I bought my $14 student ticket online, and the attendant at the front desk printed one out for me when I got there. I walked into the museum proper and took the elevator straight to the sixth floor, where the exhibit in question is located.

When you walk into the “Death is Not the End” exhibit, you are greeted by ethereal white fabric hanging from the ceiling and along the stair handrails. Hanging within one of the opaque curtains of fabric is an illuminated sign with the title of the exhibit stylized in all lowercase. Winding around custom-layout lilac walls, a combination of Buddhist and Christian art is on display.

Despite its initial appearance as a heavenly escape to macabre art, the exhibit itself is difficult to navigate and there is no particular order in which you are supposed to view the artifacts. I took the elevator up, and was blocked off from the initial wall text and explanatory artworks, since they were at the top of the stairs. Though the artworks are organized under thematic wall texts, there is a distinct lack of order and sequence that makes the exhibit unapproachable and confusing, especially to someone who is already unfamiliar with Buddhist art such as this.

The exhibit does not shy away from the taboo, the macabre or the down-right alarming. Many of the Tibetan religious artifacts are carved from human bone, and the existence of skeletons or depictions of hell in almost all of the artworks on the wall is enough to give you the shivers. But I believe that this is the exact reaction that the curators are looking for. Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhist art is juxtaposed with medieval Christian art in this exhibit on death and the afterlife. The introductory wall text of the exhibit charges Western viewers to consider how they think about religion and death. Even though the introduction wall text calls into question the West’s relationship with Buddhist beliefs, it also calls attention to the similarities between Buddhist and Christian belief systems and thoughts on the afterlife. While thinking about the juxtaposition of Buddhist and Christian beliefs is incredibly interesting, the purpose of integrating Christian artworks draws away from the importance of the Rubin Museum’s mission, which is to help make Buddhist and Asian art accessible to people in the United States.

My favorite piece that I saw at the exhibition was humble and easy to miss. Along the slightly hidden last wall you walk past as you exit the exhibit, a small, square, wooden carving is propped up in a display case. It is a traveling shrine to the Buddha Vairochana from the ninth century. The carving is interesting because of the context of where it was found and its materials shed light on the vast trade networks that connected Asia at the time. I liked the piece because the intricate artistry and modest elegance of the woodcarving really touched me, especially when you compare it to the grand, eye-catching and colorful pieces in the rest of the exhibit. This traveling shrine is intensely personal, and humanizes a religion with which I was unfamiliar before coming to this exhibit.

Despite my reservations about the navigability of the exhibit and the accessibility of the artifacts, “Death is Not the End” is definitely worth the visit. The museum is easy to get to on the 1 train from Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus, it’s open from Thursday to Sunday and the Chelsea neighborhood is teeming with great spots for a bite to eat after you explore this mecca of Asian art. The exhibit is intimate and unique when compared to other museums in Manhattan.

A visit to the Rubin Museum, and a trip to the sixth floor exhibit, are a wonderful way to spend an afternoon.