A Poet’s Examination of His Incarceration: “Felon” by Reginald Dwayne Betts

Even on its cover, Reginald Dwayne Betts’ third collection of poetry, “Felon,” engages with nuanced artistry to dissect the lasting effects of the prison system on Black communities in America. Circulating between legal commentary and horrifying stories, Betts is unapologetic in sharing his personal experiences with incarceration and redemption, writing “All I’ve done. Why regret this thing I’ve worn?” Where the American legal system and consciousness lack understanding and compassion, Betts’ poems strike the core of America’s harmful practices using his personal experiences.

Betts, a current doctoral student at Yale Law School, writes frequently in his poetry about his experience with incarceration. At 16, Betts hijacked a car, confessed to the crime and was sentenced as an adult — despite his age — to nine years in prison. Following his release, Betts published multiple collections of poetry, passed the Connecticut bar exam and established himself as a needed voice in contemporary poetry.

In detailing his experience with incarceration in “Felon,” Betts’ poetry emerges as individual accounts of a universal truth for Black Americans: The racism and incarceration that subjected Betts to ample amounts of mental and physical anguish are systemic and profoundly damaging to his community. From his opening line, “Name a song that tells a man what to expect after prison; / Explain Occam’s razor: you’re still a suspect after prison,” this collection of poems is contextualized in strong poetic traditions yet represents something not talked about enough in society: the effect of mass incarceration on individual bodies and minds.

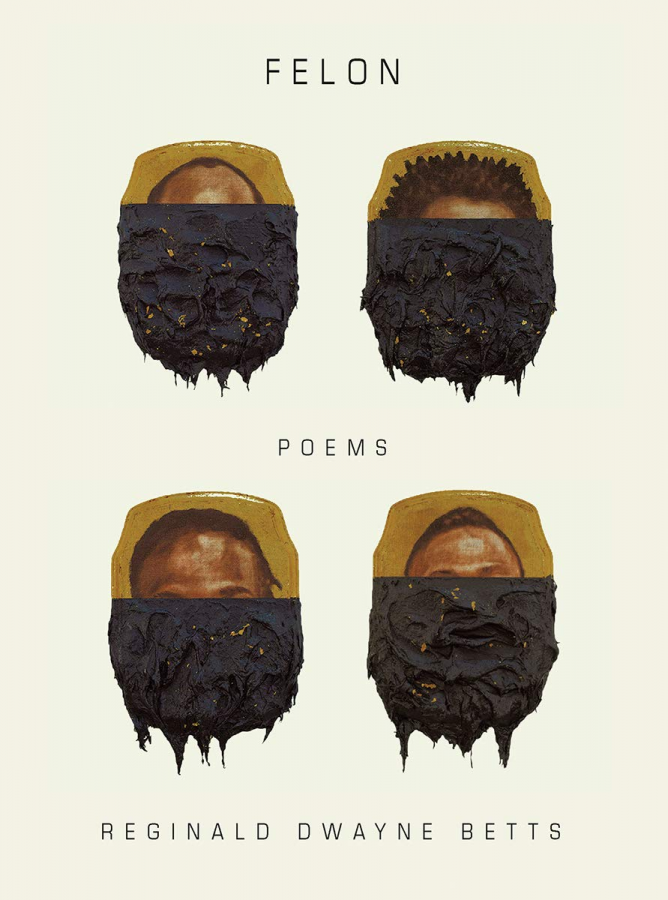

Even the collection’s artwork, made by artist Titus Kaphar, beautifully collapses artistic traditions with contemporary complexities. The cover, composed of four portraits of Black men dipped in tar, shows the effect incarceration has on disrupting identity. The violence of dipping someone’s likeness in tar is representative of the lack of resources for incarcerated peoples after their time in prison. These striking images — one of which is said to be Dwayne Betts — are a miraculous introduction to a collection that experiments in form and artistic medium.

One such disruptive form is blackout poetry, which Betts uses three times in the collection to show how systems of incarceration are not designed to help communities but instead work to commodify the bodies and minds of incarcerated people. Particularly, one of the blackout poems is about the petition of a 63-year-old man whose bail is set for $600,000. In his selection of words and phrases, Betts’ interpretation of this petition shows how America’s legal system tells Black men they are guilty until proven innocent and unequivocally establishes the existence of the prison-industrial complex.

This evocation of larger narratives about race in America is beautifully articulated through the collapse of images of slavery and prison, as Betts writes, “the corridors / before him are as long / as the Atlantic, each cell / a wave threatening / to coffle him.” As Atlantic waves representing the compounded trauma of generations of Black Americans push on his mind and body, the corridors of prison are no different: Each cell represents another exploitation of the mind and body by the American government. This collapse — which is masterfully done in several of the collection’s poems — evokes the contemporary in history, contextualizing the need for his poetry and defending his existence.

Moreover, Betts’ writing is unafraid to explore what many authors avoid discussing. His explicit ownership of his past actions, including domestic violence and alcoholism, stand prominently in his poems and express the reverberating effects of the American prison system on past felons. These poems are not excuses for his actions nor justification for the harm he inflicted; they expertly render the prison system’s flaws as fact, and perpetuate the need for change. His hope for poetry in global betterment and reckoning is evident and needed in contemporary publishing