To be entirely transparent, my excursion to the Whitney Museum of American Art was one primarily of practicality. Yes, I had a strong desire to visit the farthest and most mysterious of New York’s major art museums. I am an aficionado of modern art. I relish the advancements and abstractions of creative thought throughout the twentieth century. With that said, I ended up in the Meatpacking District because of an internship application, hopeful that a walkthrough of the museum would bolster my knowledge of the Whitney and its values. Coincidentally, the museum’s focal exhibit, “Edges of Ailey,” happened to be in its closing weeks, providing me an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone.

As my elevator rose to the highest of the museum’s eight stories, it stopped briefly on the fifth floor, the home of “Edges of Ailey.” As the doors opened, a flash of red smeared the chrome walls around me. Mary Lou Williams’ “Our Father” reverberated. For a brief moment, I was entranced. As she crooned, I was transported to a wood-paneled chapel in rural Texas. Passionate churchgoers jerking and jiving around me lost in a soulful landscape of sound and color. Quickly though, the doors closed and I returned to reality.

Before I discuss the nature of the Ailey exhibition, it is necessary that I provide a precursor for my experience. The Whitney is a brilliantly curated museum. Works from the collection are carefully displayed and arranged. With that said, it has a tendency (as many art museums do) to seem fairly redundant. As pieces come one after another, it is easy for them to blur and lose individuality. That may be a result of my inadequacies as an art viewer. But nonetheless, I entered “Edges of Ailey” exhausted. My legs ached, and I ambled slowly into the red expanse that had been teased earlier. However, what I would experience over the next hour was worth a temporary physical discomfort, as its spiritual and emotional implications left an irreparable mark on my soul.

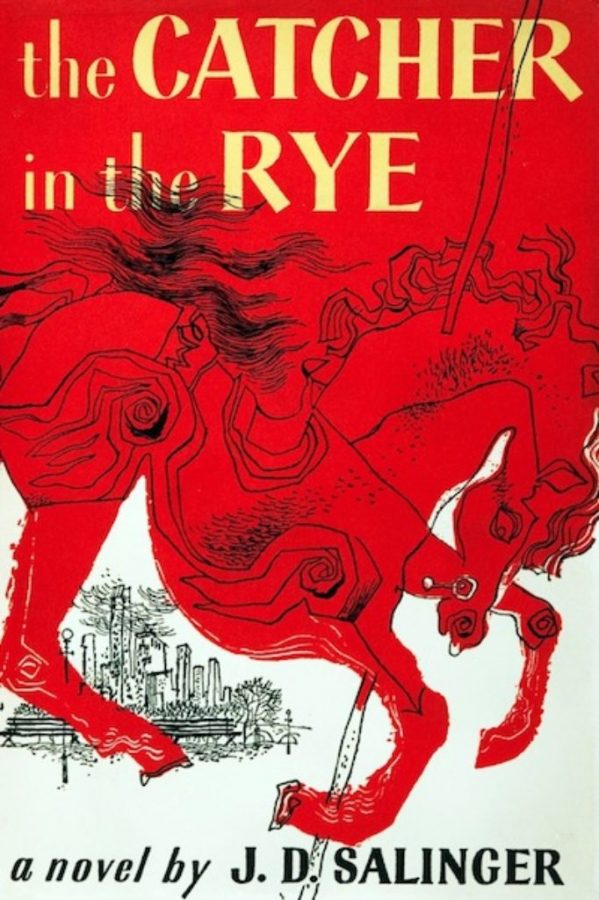

A red board loomed directly ahead of the elevator. Succinctly, it described the alternative approach to representation that I found intriguing: “The breadth of this exhibition reflects the ambitions of the artist who said ‘I wanted to paint…I wanted to sculpt. I wrote poetry. I wanted to write the great American novel…” This was not to be a demonstration solely of the work and concepts created by Alvin Ailey, but rather an insight into his influences from Black America, both rural and metropolitan. These influences serve to enhance the meaning of Ailey’s work. A display of only Ailey’s writings and dances would be visually intriguing, but with the addition of societal context, “Edges of Ailey” makes the leap from experience to memory.

The room is rectangular, but with the aid of stunning visual layout and curation, its direction is in many ways sporadic yet organized, a thoughtful allusion to the choreographing of dance. Each section touches on a specific area of influence for Ailey, weaving in both his thoughts on the subject and pieces created under the influence itself. For example, the section directly adjacent to the entrance covered tribal African culture. Enclosed in a glass case was a pair of crafted hand drums from the late eighteenth century. On the table just after were letters written between Duke Ellington and Ailey, discussing the creation of “Liberian Suite,” their tribute to the Liberian Republic’s centennial. This idea of interlacing influence with execution continues throughout the exhibition, as themes range from spirituality and music to femininity and homosexuality.

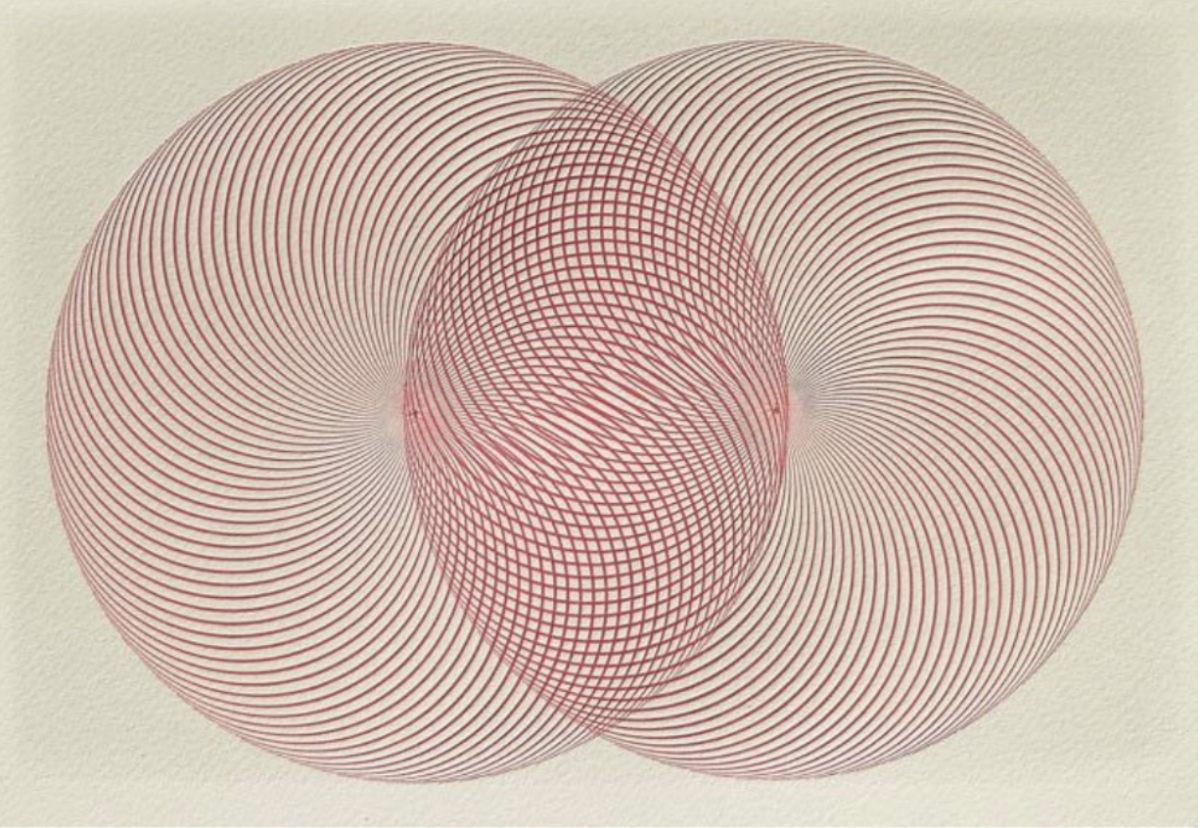

This alone, though, is relatively typical of an exhibition documenting the work and life of an individual. So, what exactly gives “Edges of Ailey” the added component of soul and resonance? Along the top of the red walls was a stripe of screen about fifty yards long, itself broken into various segments connected by a main idea. As I explored the section about spirituality, already moved by depictions of African American laborers attending mass and performing religious acts, I was startled by a light drone booming from the speakers overhead. Once I turned, I noticed multiple videos of a woman dancing with a single white cloth, her movements loose and pensive. The dance was Alvin Ailey’s “Cry.” I realized soon after that the drone was the musical pairing to the piece, Alice Coltrane’s “Something About John Coltrane.” As the piano came in, I stepped forward and observed the dancer, in the process exposing myself to the relationship between dance, music and the communication of raw emotion. As tears filled my eyes, I came to a realization. I know very little of the struggles that African American people faced. Yet through these contortions, paired with a somber melody, I was able to achieve an insight into Alvin Ailey’s experiences, experiences shared by a community that has endured immense strife.

I was never appreciative of dance as an art form. I believe it has something to do with my own movements. At times I feel robotic, and as a result, the idea of expression through movement seemed foreign. I am grateful to “Edges of Ailey” and The Whitney for freeing me from this self-absorbed attitude. Observing art created to serve a community neglected by the mainstream is powerful in its transparency. Ailey was a trailblazer for dance, in addition to the African American and queer communities. He paved the way for a new school of thought that persists in spite of his passing and will continue as creatives explore mediums of expression for their hardships. “Edges of Ailey” is a mere step along the path, a testament to the enduring power of expression, bridging the past and future of cultural identity.