Aquaman Swims to Heroic Success

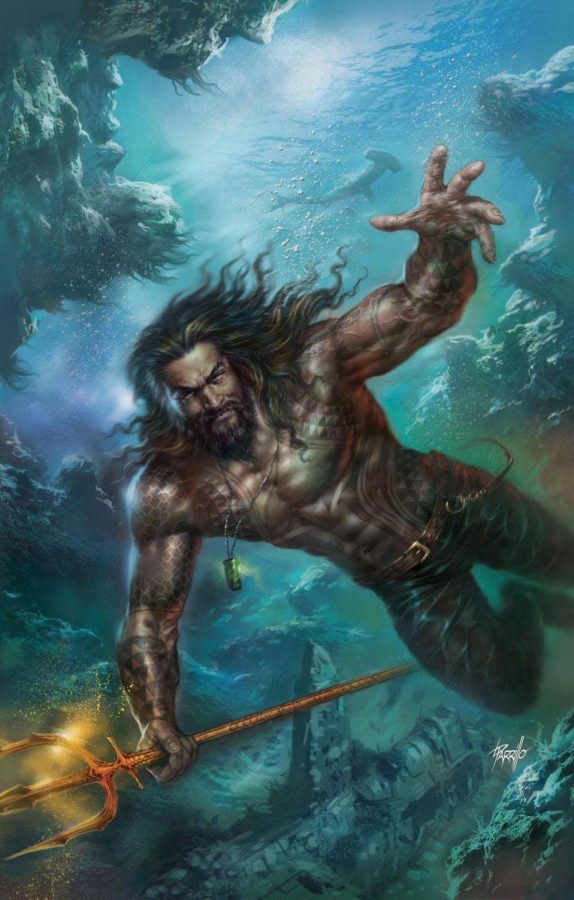

Early on in the underwater action sequence of “Aquaman,” Dolph Lundgren rides into battle on a giant sea horse and fires a laser sword at a crab-person warrior. That brief action illuminates many aspects of the film. “Aquaman” is a breath of fresh air (no pun intended) for the superhero franchise, trading the overwhelming darkness of “Batman v Superman” and the inconsistent tone of “Justice League” for a whole-hearted embrace of outlandish fun, weaving a compelling story around Jason Momoa’s unique take on the titular character.

The film begins with the story of Aquaman/Arthur Curry’s birth. Thomas Curry (Temuera Morrison) falls in love and has a child with the queen of Atlantis, Atlanna (Nicole Kidman). Atlanna tells the baby, Arthur, of her hope that he will one day unite Atlantis and the surface world. However, Atlantian soldiers force Atlanna to return to her kingdom, leaving Thomas to raise the boy by himself. Despite their brief screen time together, Kidman and Morrison have an intriguing chemistry and imbue the film with a dose of classic heroic tragedy.

The adult Arthur struggles to reconcile the two sides of his heritage. He’s not afraid of his powers, like so many other screen superheroes are early on, but he has no time for Atlantis. It’s only after Mera (Amber Heard), an Atlantian acquaintance, warns him of the current king, his half-brother Orm’s (Patrick Wilson), plan to make war with the surface that Arthur is forced to confront his true destiny. The plot revolves around Arthur’s quest for a legendary trident that will grant him the power to overcome his half-brother’s forces.

Arthur is already an active and famous crime fighter on the surface after the events of “Justice League.” This allows the film to launch into the action and character development quickly. The film’s most successful storyline is Arthur’s journey as he reluctantly moves from being, as he puts it, a “blunt instrument” against evil, to a more fully realized hero, capable of leading Atlantis. The character has internalized a lot of the discrimination he has endured from right-wing Atlantians. His arc of coming to accept his half-blood status, in combination with Momoa’s own mixed heritage, gives a message in support of the multi-racial community.

While Morrison and Kidman may get the credit for initially drawing the viewer into the story, it is Momoa who keeps them there. The actor’s obvious enthusiasm for the role sells the film’s 80s action movie cheesiness and some of the silly comedic beats. He also has a gentle compassion and a brooding intensity that serves him well in the quieter character moments. The scenes in which Arthur learns to better himself and defiantly stands up for who he is against are immensely satisfying because of Momoa’s wholehearted conviction. Amber Heard alternates between being lovely and fierce in equal measure. Heard’s character development isn’t especially profound, but still conveys subtle change as she abandons her assumptions of Atlantian superiority in favor of a more compassionate outlook.

The dynamic between the two leads is perfectly balanced. Mera is usually the brains of the operation, while Arthur handles more of the brawling. However, Mera is no pushover in a fight, and there are some fun displays of her ability to control water.

The strength of the supporting cast speaks to how well-rounded the film is as a whole. Orm is not the kind of villain who’s sympathetic nor is he an anti-hero. He is a bad guy through and through out for world domination. Orm actually benefits from this, giving a sneering, grandiose performance you’ll love to hate. Also on the villain front is Black Manta, a pirate with a grudge against Arthur, brought to life by an intense, scene-stealing turn from Yahya Abdul-Mateen II. Dolph Lundgren is imposing and authoritative as Mera’s father Nereus, king of the underwater kingdom, Xebel, who allies with Orm. Dafoe is clearly having a blast, playing essentially an Atlantian version of himself, and his character provides nice warm support to Arthur/Momoa.

Still, if there is a star of “Aquaman” other than Momoa, it is the sheer technical wizardry on display throughout much of the film. In terms of scale and spectacle, Aquaman easily dwarfs all other DCEU films and all but the biggest Marvel entries. Director James Wan and company have done remarkable work in bringing the fantastical world of Atlantis to life. Moments such as Arthur’s first entry into the capital city are breathtaking, even when the viewer knows they are completely digitally manufactured, thanks to the excellent work done by cinematographer Don Burgess and the visual effects artists. Burgess makes some spectacular compositions throughout the film, both in scenes on the surface and below. More than any of its predecessors or contemporaries, “Aquaman” fully realizes the colorful vibrancy of superhero comics.

Wan, not content to let the stunning visuals be static, fills the film with a multitude of expertly staged action sequences, captured often in smooth, tracking coverage. Just as the film risks slowing down for too long, it launches into another exhilarating fight or chase. “Aquaman” has almost double the action scenes than most other blockbusters.

I particularly enjoy a Sicily-based brawl between Arthur and Manta, which happens in tandem with a rooftop chase between Mera and some Atlantian thugs. Also worth noting is the absolutely massive finale, essentially an underwater equivalent to a battle from “Lord of the Rings.”

“Aquaman” is not without its flaws, but it is the kind of film that is so riotously fun that a lot of them can be overlooked. Little things like clunky dialogue and stylistic quirks just don’t seem to matter that much when you’re spending time with likeable characters and being treated to a wide variety of exciting set pieces. Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman is still DCEU’s best cinematic hero, but Momoa’s Aquaman and the world he inhabits are fantastic additions to the franchise’s new foundation.

For the first time in a while, the future of the DCEU looks bright.

By Greg Mysogland