By Adam Payne-Reichert

There’s something uniquely enjoyable about seeing live music. People might argue as to where this special quality originates, be it from superior sound quality or highly stimulating visual effects, but what really makes live music so experientially unique is its human quality. The music becomes more analogous to human existence, vulnerable to mistakes but equally capable of taking on an evolved form. Moreover, the perceptible effort which any decent artist puts into a show reminds us of the highly intricate process which led to what we’re currently hearing.

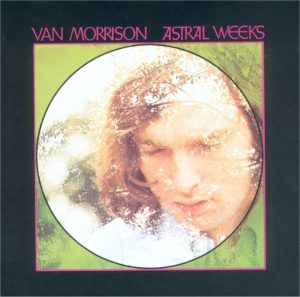

Music recorded in the studio and then consumed in various digital formats have trouble retaining this sense of humanity. However, in his 1968 album Astral Weeks, Van Morrison uses nearly every trick at his disposal to artfully overcome this obstacle.

Morrison and his studio band recorded this album over the course of only three sessions, with Morrison refusing to hand out lead sheets to the musicians and instead encouraging them to play what they felt fit the melodies he brought them. The effect that these recording procedures had upon the final output is immense. The instrumentation is clearly thoughtful and complex, but it also feels very spontaneous and lively. The production, similarly, could be said to suffer from lacking instrument separation, but unusually, this actually contributes to the intimate feeling of the music and thus helps to accentuate its human qualities.

Consider the second song in the track list. The melody of this song is rooted in the guitar and bass parts, but the low volume of these parts suggests that they may be included more for the musicians’ benefit than for the listeners’. What instead stands out is the vibraphone, flute and lead guitar riffs, which accentuate Morrison’s vocal flourishes.

Despite the creative pressures that such a recording process puts on individual musicians, Morrison and his studio band were able to push themselves creatively and ensure that a variety of sounds still exists throughout the album. “The Way Young Lovers Do” has a much more intentionally orchestrated sound, with horns and strings working in sync to complement Morrison’s vocal swells and retreats. “Slim Slow Slider,” at the other end of the spectrum, employs spacious, minimalistic arrangements to a hauntingly beautiful effect. The sonic distance between the flute and the bass on this song, developed both through the stark difference in registers and in tempo, potently attests to the sense of distance this song’s narrator feels from his former lover and the contrasting emotions that come along with this longing.

The lyrics work in tandem with the instrumentation to highlight the human qualities and messages of the music. Morrison’s lyrics describe a variety of different, but usually pastoral, scenes and different, but usually lovelorn, characters. His writing is impressionistic and based in stream-of-consciousness techniques, and as such, the lyrics are highly interpretable. Although this might frustrate some listeners, this aspect speaks to human experience: meaning is rarely inherent in something, and we’re left to interpret and find meaning in whatever way we choose.

This isn’t to say that the lyrics are nonsensical. The title track clearly discusses the narrator’s regretful remembrance of a past love and desire to occupy a different plane of existence, one where he can visit this former lover and “be born again.” “Beside You” beautifully reflects on how, when you are with your true love, the connection is such that you never question why this pairing came to be, for it is immediately clear that it had to be. Likewise Morrison’s singing, employs a variety of different tactics to underscore the album’s passionately improvisational feel. In “Beside You,” Morrison accelerates past the tempo of the band to repeat the line, “You breathe in, you breathe out,” reflecting the nervous energy present when you have to remind yourself just to breathe.

In recording this album, Morrison was driven by many of the same radically innovative tendencies that produced The Velvet Underground and Nico. Yet a stark difference exists between the two records. The VU’s first album has since influenced a huge array of musical genres, and the record consequently sounds far less revolutionary to contemporary ears. Astral Weeks, on the other hand, continues to stand in stark contrast to a contemporary music scene that all too frequently abstracts from human qualities, taking sex for making love and consumerism for the fulfillment of life’s pleasures. And if past behavior is the strongest indicator of future behavior, the need to reaffirm the fundamentally human aspects of our experience won’t be lessened anytime soon.