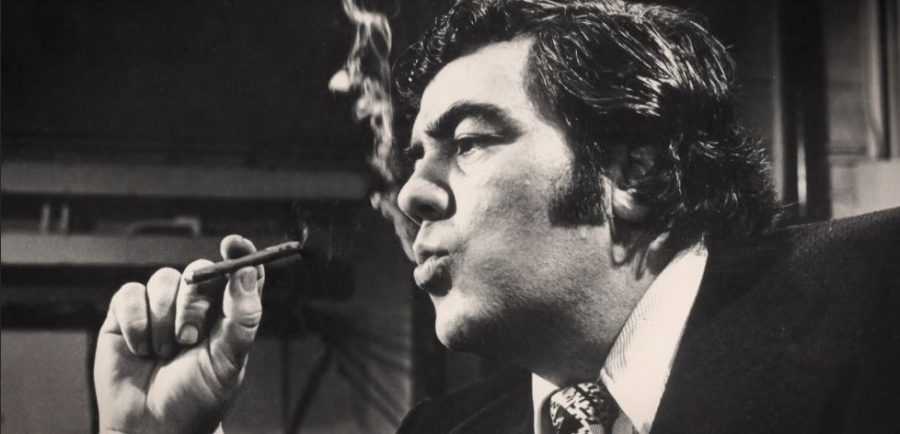

“Breslin and Hamill” Evokes Nostalgia for Old style Journalism

The HBO documentary “Breslin and Hamil “tells the story of two famed New York journalists in the ’70s and ’80s. (HBO)

This week, I found myself on a friend’s couch watching the new HBO documentary “Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists.” HBO documentaries are usually a safe bet for two hours well spent, and I was particularly taken with “Deadline Artists” and the narrative of local New York City journalism it constructed.

Through interviews with seasoned reporters, screenwriters, activists, authors and other New York notables, HBO pulls the viewer down a rabbit hole to a semblance of old New York. You will find few college degrees in the halls of the New York periodicals at this time. Instead, journalism is a boys’ club of working class men with enough romance and anecdotes to fill volumes.

Long before the New York Times became the world’s journal of record and New York journalism became global coverage, HBO shows us what local reporting meant to a community that just happened to be the center of the world.

Through grainy footage of old interviews and careful oration of classic news columns, the documentary tells the story of New York journalism through two of its greats – Pete Hamill and Jimmy Breslin. Both were columnists for local city publications from the ’60s through the early 2000s.

The film leans on Breslin as its star, with Hamill as something of a foil. Breslin’s boorish genius takes the stage. We see his temper and his wit in footage captured before his death in 2017.

In contrast, the documentary depicts Hamill as a more sensitive, brooding version of the city news man. Both came from relatively poor Irish families, but Hamill is depicted as more encumbered by his past, while Breslin chooses to leave early childhood tragedies of an absent father and troubled mother as hard facts of life not meant to be overanalyzed.

By juxtaposing these two temperaments, the documentary places the two journalistic styles in contrast: Hamill acts as the sensitive poet, while Breslin is the uncouth genius.

But these character studies seem to be tools for the documentarians to examine the greater character – New York City. Through Breslin and Hamill’s columns, we see cycles of the city. We see the assassination of a president, the crime and ensuing pack mentality of the ’70s and ‘80s, the AIDS epidemic, political corruption and organized crime through the colorful and vibrant writing of Breslin and Hamill.

The documentary relies on their columns as much if not more than collected interviews. HBO takes the viewer through the decades of New York City through the lens of Breslin and Hamill’s columns. We hear the city in their voices.

The film also does a good job of acknowledging that there are biases within any storytelling. The filmmakers present Hamill and Breslin as men with backgrounds and opinions in order to remind us that, while their columns open a window into the city, we are looking through Breslin and Hamill’s window. It also is clear to paint them as legends in the field, but not heroes.

The film is unafraid to touch on their missteps, arrogance and scandals, from Breslin’s sexist and racist comments to Hamill’s battle with alcoholism. The storytelling allows for them to be men who were imperfect, but still worth a film’s exploration.

In the same way that Breslin and Hamill’s columns were love letters and compassionate critiques of their city, the documentary is a love letter to the style of journalism Breslin and Hamill practiced. Its call to action is for local coverage. It highlights the steep decline in the number of local city reporters.

The movie spends its time praising this style of reporting only to lament that it is an artifact of lost era. It spins a tail of journalistic titans, writing true columns that read with the gripping hold of fiction, only to turn and declare through the mouths of multiple interview subjects that that time is gone.

We will have no more Breslins or Hamills. There is no longer a place for stories to be told in this way.

While it is true that city publications amputated their local coverage as they began to bleed funds, and beloved community papers changed hands and changed styles to keep from closing their doors, or folded altogether, the film shifts tone sharply. For a movie so committed to praising the work of journalistic legends and their commitment to continue fighting for a higher level of reporting amidst changes to the industry, it seemed strange that it would so decidedly abandon hope at the end.

Regardless, it is certainly a treat to fall into old New York through the eyes of Breslin and Hamill, and think about how its landscape has changed through time and diligent reporting.

By Aislinn Keely