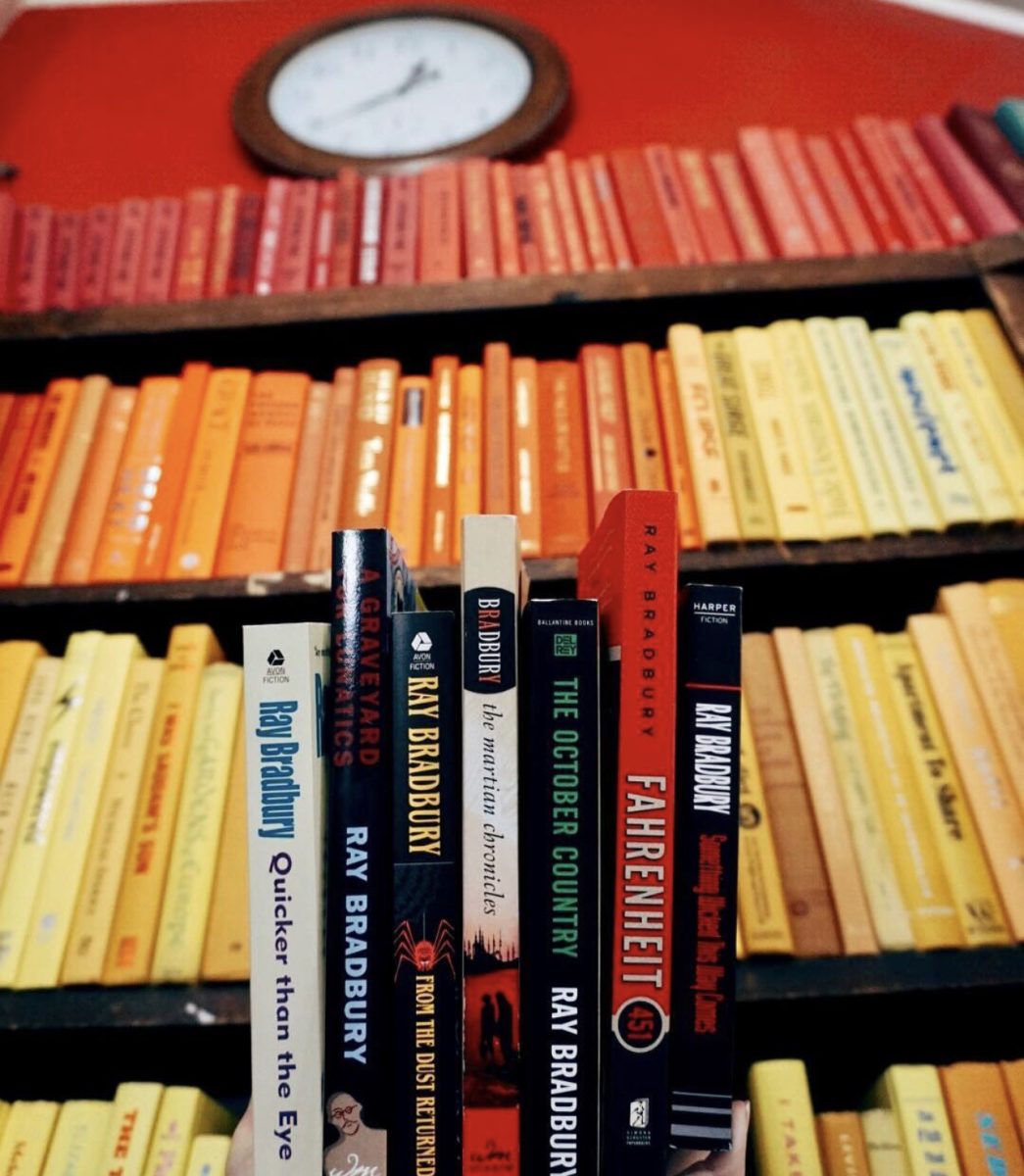

Anyone who knows me well knows that I adore Ray Bradbury, almost to a fault. I wrote my college entrance essay about him. I quoted him in the speech I gave at my high school graduation. This past summer, I got my first tattoo: black linework based on the cover of Simon & Schuster’s 2012 edition of Bradbury’s “The Martian Chronicles.” And here I am, writing about him and his work again.

My fascination with Bradbury’s writing borders on obsession. He is prolific. He wrote about everything, and pretty much all of it is good. He wrote about childhood, science-fiction, the Midwest, nuclear fallout, environmentalism, technology, censorship and government corruption. His works were well-respected during his time and after for their compelling images, powerful analogies and insightful social commentary, but to me, they are so much more.

The first time I read Bradbury’s work, I was in my sixth-grade English class. My teacher at the time, the wonderful Mr. Farmer, assigned to us one of Bradbury’s short stories: “The Veldt.” It’s a haunting tale about how unbridled technology can corrupt family structures and eat away at the simplicity of childhood. As the blossoming adolescent I was, learning that she could, in fact, disagree with her parents, the story struck a chord.

It was around this time, in early middle school, that I discovered my own interest in writing and telling stories. I wanted to be able to tell stories like Bradbury. His writing is accessible while still being wonderfully imaginative. He wrote for everyone from sixth-grade girls to burnt-out 20-somethings to professionals on the brink of retirement, and I wanted to emulate that. I still do.

Since reading “The Veldt,” I’ve read a slew of his other works enthusiastically, attentively and earnestly. I mean, “The Veldt” is just one of the hundreds of poignant, before-their-time stories that Bradbury wrote in his nearly 70-year career. Of course, he is most well-known for his novel, “Fahrenheit 451,” which includes similar themes about technology, government corruption and censorship that are present in his other stories, but “Fahrenheit 451” is just the tip of the iceberg that is Bradbury’s oeuvre.

“Fahrenheit 451” is an indisputably great novel, but it would be a shame to go through life having only read one of Bradbury’s books. It would be a shame to miss out on the childhood lessons and sticky nostalgia of “Dandelion Wine,” a shame not to ponder age, adulthood and fear alongside Jim Nightshade and William Halloway in “Something Wicked This Way Comes.” It breaks my heart to think that not everyone will have the great pleasure of experiencing the monotonous beauty of the American Midwest through the eyes of Ray Bradbury in his loosely compiled Green Town series. I can’t imagine a world in which I hadn’t read “There Will Come Soft Rains” or “And the Moon Be Still as Bright.” I simply would not be the same person without these stories.

But above all of these, the most formative of his novels, the book that solidified my infatuation with Bradbury, was “The Martian Chronicles.” The book is like a puzzle, a beautiful anthology made up of around 26 short stories. It tells the story of the colonization of Mars by Earth-born humans, and in doing so, forces the reader to confront the systems that they exist in and contribute to. It’s a thinly-veiled anti-colonial piece. It tackles issues like environmentalism, racism, and sexism through the compelling analogy of Earth-Mars relations.

I’ve read the book in full a couple of times, but the true beauty of an anthology is the ability to go back and read small sections at a time, sections that spoke to you most. Bradbury’s “And the Moon Be Still as Bright,” which I mentioned before, is perhaps my favorite section from the entire novel. It follows the arrival of the fourth American expedition to Mars. By the time the astronauts arrive, nearly all the Martians have been wiped out by disease, brought on by exposure to the previous expeditions. My personal hero and the featured character of this story, Jeff Spender, emerges as a defender of the remaining Martians and admonishes the rest of the crew for their failure to respect Mars’ environment, culture and the tragedy forced upon the Martians by colonization.

In the background of this entire story is the looming threat of nuclear fallout on Earth, a theme that Bradbury writes about in many of his stories. The book forces the reader to ask themself serious questions and confront their own moral beliefs. What would you do? If you had the money to escape nuclear fallout on Earth by traveling to Mars, would you do it? Would it be worth it to save yourself at the risk of thousands of Martians’ lives, taken or disrupted by colonization? Whose side would you take?

That is how you know that “The Martian Chronicles” is a good novel. It upsets you. It creates this hypothetical dilemma and transforms it into something real. You can’t read any of Bradbury’s works in peace, and that is why they are so important. A truly great work of art should make you uncomfortable. It should reveal truths about the world and also about yourself. Bradbury’s truths — revealed to millions of other readers like me — have made me forever grateful for the impact that his writing has had on my life, and I anxiously await the day that my own writing might have that sort of impact on someone else.