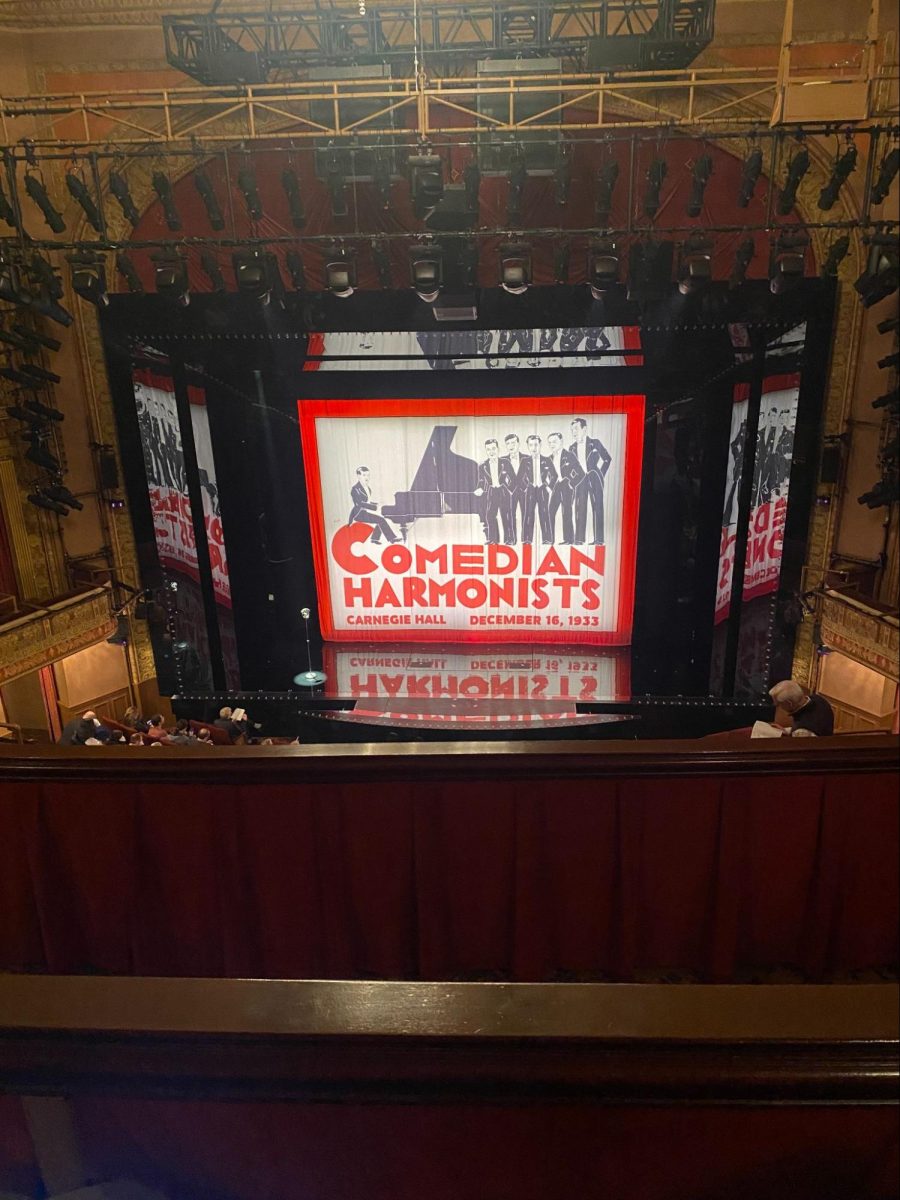

When we spend money on a Broadway ticket and shlep across town to see it, we come with expectations. Theater-goers who saw “Harmony” at the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene expect to see roughly the same show at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, where it opened on Nov. 13. Barry Manilow fans might expect a jukebox musical with his familiar tunes, which — spoiler alert — it is not. But for most, this is a new show with a title that does not give too much away. So far, audiences only know the omnipresent slogan: “The extraordinary true story of the greatest entertainers the world would ever forget.” The entertainers in question are the Comedian Harmonists, a German singing group that was very successful in the 1920s and early ’30s. Although largely forgotten in the postwar years, the 1976 documentary “Die Comedian Harmonists: Sechs Lebensläufe” by Eberhard Fechner initiated a Harmonists renaissance in Germany. Since the Harmonists’ rediscovery, the group has been baked into German popular culture like Elvis and the Beatles. So what about the historical accuracy? To be clear, every artist certainly has the right to take liberties with their rendition of events; after all, we do not expect a lesson in Tudor history when we come to see “Six.” But a musical that so insistently harps on telling the “true story” must be measured by its tagline and the degree to which it lives up to it.

This review is a class project written by the students of “Frisch aus der Presse,” a German class at Fordham University, that saw a preview of the show on Oct. 24. We hope to provide a much-needed additional perspective that is informed by our background in German literature, culture and history, and that allows us to fact-check the musical’s claim of telling the “true story” of the Comedian Harmonists.

Coming to a musical about a prominent historic group of singers, we expected the score to be heavily influenced by their original work, and were disappointed by the lack of any of the Comedian Harmonists’ songs. Still, some of the numbers did shine for their incorporation of comedy, for instance the costumes and choreography of “Come to the Fatherland,” which featured the six harmonists attached to Nazi puppet strings hanging from the ceiling. Their suggestive number “How Can I Serve You, Madame?” probably came closest to replicating the Comedian Harmonists’ work because it had a comedic flair that was reminiscent of the true musical group, which got its name from their frequent use of jokes. The Comedian Harmonists had a distinctive comic style and a repertoire that is remembered and cherished to this day, so it was a missed opportunity to not include a recording of the actual group or a remake of one of their popular songs at some point in the show.

For a show advertised as a true depiction of the Comedian Harmonists and the Berlin of 1927 to 1935, capturing a credible atmosphere is imperative. Astonishingly, the cast lacked any resemblance to an authentic German intonation, butchering the pronunciation of any German word uttered throughout the musical. Even the name of the German government, “Reichstag,” was severely mispronounced. For a generic, Americanized performance, this might be acceptable. But it is hard to imagine that this show would appeal to a German audience or anyone with a basic knowledge of the German language. All in all, “Harmony” is a very flashy, entertaining show about an important German group. It just doesn’t happen to be particularly German. Or representative of the group’s music.

Instead, Manilow and Sussman have chosen to tell the story of the Comedian Harmonists through a deliberately hyper-Jewish lens. For example, although all six band members had wives, their musical depicts only the two couples that crossed Christian and Jewish lines to wed. More disturbingly, in this show, the fictionalized version of Erich Collin self-identifies as Jewish. In actuality, Erich Max Adolf Collin was a born, raised and baptized Protestant, as was his older sister. Both siblings used their Christian mother’s surname; their Jewish identity was imposed on them by the Nuremberg Laws. Manilow and Sussman add insult to injury when they suggest otherwise.

In many ways, “Harmony” seems tailored to appeal to Jewish ticket-buyers. This Jewish connection can telegraph meaning; Mary’s reference to the Book of Ruth instantly recalls the story of a convert to Judaism who, like Mary, follows her new family and their faith with legendary devotion. Still, at other times, Jewish references seem ham-handed. A non-Jewish audience member may sympathize with the elderly Roman Cycowski, known as “Old Rabbi,” and his unceasing repetition of the Hebrew prayer “Shema Yisrael.” The old man is clearly experiencing something moving. However, more conservative Jewish audience members may be shocked that the prayer lacks the substitution of “Hashem” for references to the divine name so as not to say God’s name in vain. (Such a substitution was indeed made by the cantor in the 1999 German film about the Comedian Harmonists.) The line crossed by this offense is somewhere between blasphemy and poor taste, and the show would certainly be improved by the substitution.

Old Rabbi is the narrator of the musical. The inclusion of his narration proves to be a wise decision on Manilow and Sussman’s part because it provides context, explains the reasoning behind certain actions and links the different scenes together. Thus, we are being told the story from a distinctly Jewish perspective with Old Rabbi, who was the last member of the group to pass away, as the narrator. Chip Zien does an admirable job, effortlessly portraying the old, wise man who reflects on a wondrous yet tragic time in his life. The real-life Cycowski was a cantor who trained to be a rabbi, which carried over into the musical. The production stayed true to its source material and explained how, along with Collin and Harry Frommermann, Cycowski had to leave Germany due to the Nazis’ Nuremberg Laws. Both in real life and in the musical, Cycowski loved Germany and thought of it as his home. He was completely devastated to see his beloved nation descend into chaos when Hitler came to power. With decades of hindsight, Old Rabbi can now point out to us in retrospect where things went wrong.

The plot is so focused on Old Rabbi and his memories that the musical is de facto about him, rather than the young Comedian Harmonists. His narratorial presence on stage steals much of their spotlight: he has as many songs in the show — plus most of the dramatic scenes and some silly interludes — as the rest of them combined. During periods of prolonged dialogue, or during duets, the actors mostly just stand still with their hands at their sides. Small things like buttoning a coat, polishing a glass, tying something, writing something down, reading or fixing collars could all bring the characters to life and make them look more natural. But director and choreographer Warren Carlyle does not make these choices. Similarly, while some functional props exist (there are shiny platters, a strategic water pitcher and signs/flyers during a bolshevik protest), the stage is mostly bare. The choreography of the dance numbers is pretty well done, but basic as well. The costumes by Linda Cho, on the other hand, are a highlight. They aid in character development and say much about personality, especially Ruth’s red coat. In a story about concealed identities, the coat shows her true colors, literally.

Not only are the six Comedian Harmonists eclipsed by the omnipresent Old Rabbi, they are additionally upstaged by the women in the show. Instead of being traditional supporting roles, their performances take up equal, if not more, stage time than the male group members get. The three women in the show each have at least one solo, which cannot be said of all the Harmonists. With Broadway favorites Sierra Boggess and Julie Benko playing the parts of the mixed-marriage wives, this is not bad news. The wives’ Book of Ruth duet “Where You Go” in the second act is beautifully written and portrays the women’s devotion to their husbands. The stage simulates two rooms separated by different lighting colors, and the minimal usage of props keeps the focus on the events unfolding within those individual color-tinted rooms. But as Mary gets closer to her husband through the Jewish faith they now share, the lack of this bond drifts Ruth away from her husband “Chopin,” ultimately deciding to split from him entirely. Mary’s more ornamented operatic style fits her hopeful outlook to the future, while Ruth’s vocals create a melancholic and repressed sound, overshadowing its counterpart. This duet alone has great potential for Tony Award nominations both for Boggess and Benko.

Barry Manilow, a celebrated artist in the world of music, took a bold step by venturing into the realm of musical theater with “Harmony.” His remarkable journey, working on this Broadway musical for three decades up to the age of 80, is clear evidence of his enduring passion and dedication to this project. However, despite our anticipation, “Harmony” failed to strike a chord with our classmates. We expected Manilow, a seasoned songwriter and musician, to deliver memorable and evocative songs. Unfortunately, “Harmony” falls short in this regard. While there are moments of musical brilliance, the overall score lacks consistency. The stereotypical depiction of all things German and the decision to omit any original Comedian Harmonists songs are missed opportunities and flatten the narrative. Manilow’s choice to write this musical as a Jewish story without getting the details right makes the whole project look more opportunistic than genuine. “Harmony” serves as a reminder that even experienced artists can face challenges when transitioning to new artistic media. In this case, the musical failed to find its own harmony, resulting in a discordant and underwhelming experience for theatergoers.

Marcia Mary • May 1, 2024 at 10:08 pm

Your review gave me a headache trying to read it. It jumps all over the place and half the time I had to reread the previous sentence to find out what you were talking about.