In a warm, dimly lit room in the Morgan Library and Museum resides countless tales and memorabilia from the revered Czech absurdist fiction writer: Franz Kafka. Before his untimely death from tuberculosis in 1924, he had written over 90 fictional works, some completed and others left as fragments of escaping ideas.

One of his most notable works, “The Metamorphosis,” is like a dream, but for the main character, Gregory Samsa, it is all too real. He, who the story is narrated from, turns from a man into a “giant, cockroach-like insect” and has to learn how to navigate his life once again. In a twisting, semi-autobiographical story of degradation and alienation, Kafka explores what it means to hold different amounts of power in modern, hierarchical society.

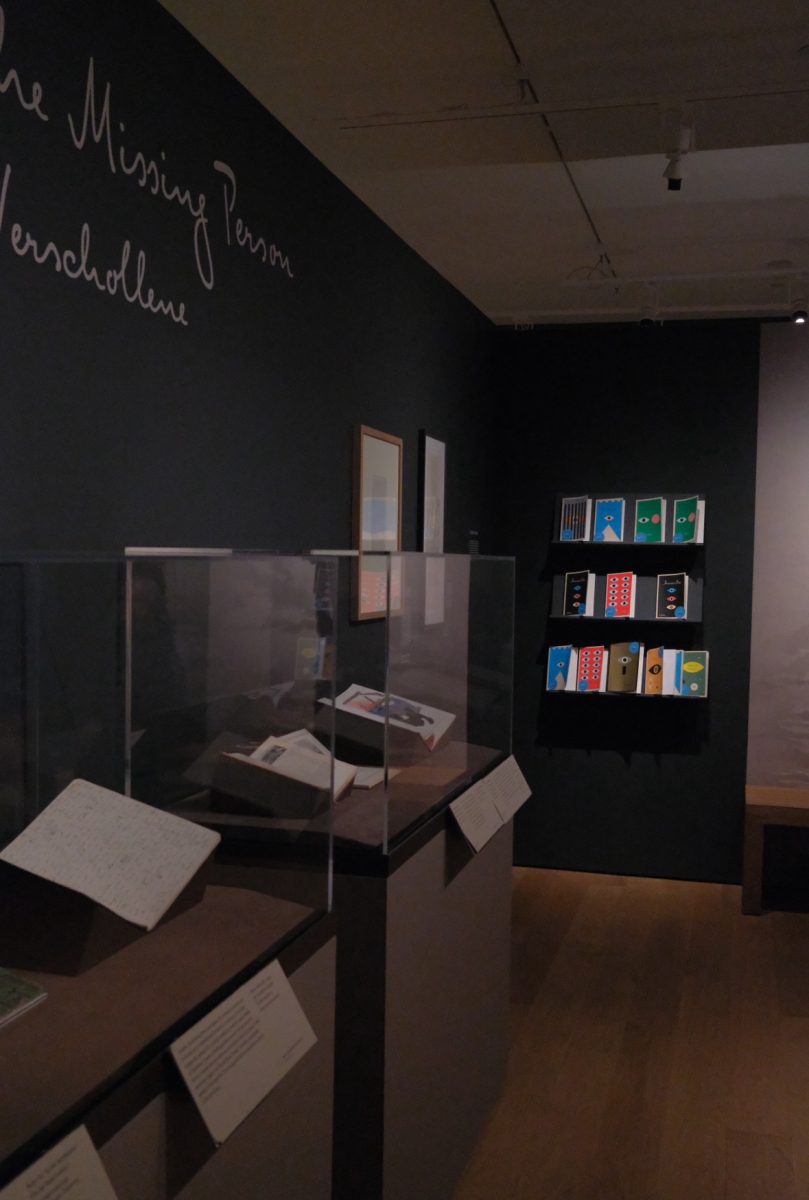

Themes from “The Metamorphosis” linger on the walls of the new Kafka exhibit at the Morgan Library. In the gallery, there are renditions of his most famous portrait, diary entries and riveting biographical information on how he began to craft the abstract out of the ordinary. His elusively surreal adaptations of life and the roles of humanity is no dream.

Kafka, a man of a simple, uneventful life but many afterlives, is the author of famous classic works such as “The Castle,” “The Trial” and “Amerika.” Born in 1883 to a German-speaking Jewish family — his father, mother and three sisters — Kafka began writing as an escape from inheriting the family business. In a diary entry, he asked the space between lines, “How to concentrate when your family is making lots of noise?”

Most of his diary entries that have been published revel in the angst and melancholy of being too lonesome for the world. Before his death, however, he left a note to his closest friend Max Bond, saying, “My last request: burn all my diaries, manuscripts, letters… completely and unread.” Obviously, that did not happen, as we are still reading his philosophies and thoughts a century later.

The Morgan Library exhibit was prepared based on the innovation and peculiarity of Kafka’s novels and short stories. American designer, Peter Mendelsund, created a suite of covers for all of Kafka’s published works in 2011. Their brilliant color palettes are highlighted even more with simplistic geometric designs mirroring the story’s contents. His covers helped inspire this exhibition, and the layout of the room itself was even designed with him. The room utilizes unique and vibrant colors paired with his handwriting printed on the walls. Under the dim lights and stuffy yet comfortable blanket of the room, Kafka’s life spreads out before the viewer like a scavenger hunt.

This exhibit first appeared under the name “Kafka: Making of an Icon” at the Bodleian Library in Oxford University since it already held a large number of his transcripts. With help from his nieces, museum curator and literary and historical manuscript associate curator, this exhibit finally resides in Manhattan until April 13, 2025.

It’s a shock, though, to wander into the Morgan with its vast windows of the café, sparkly bookstore and mumbling of conversations floating through the air and then have it all sucked away as you step through the door frame of the exhibits gallery. As if the exhibit was urging viewers to stay for a while and let the texts provide comfort — or maybe it’s the other way around.

At the end of the day, his work has remained through centuries of global and philosophical literature. However, as insightful as he is, Kafka’s work does not prescribe solutions or philosophies; instead, it embodies the questions and tensions of the modern human condition. His narratives invite the reader to confront alienation, absurdity and uncertainty without offering easy answers.