BY MADELINE KIMBALL

STAFF WRITER

The pilot episode is a television show’s first date with its audience. Its purpose is seduction; even as it displays its best characteristics, it must hint that there is more to come. It must simultaneously charm and intrigue to keep the viewer watching. Although pilots vary with the personalities of their shows, all successful ones have perfected self-branding, pacing, character introduction and exposition.

A pilot that effectively self-brands makes clear what the show is about. It labels itself with a genre and sets the tone for the entire series. It does not pretend to be a romantic comedy when in fact it is a cynical, political drama. If it has elements of both, it prepares the audience for each genre. This allows viewers to determine whether or not this is the type of show they would be interested in watching. A show that fails to self-brand drives away a potential audience and generates false expectations and resentment among viewers.

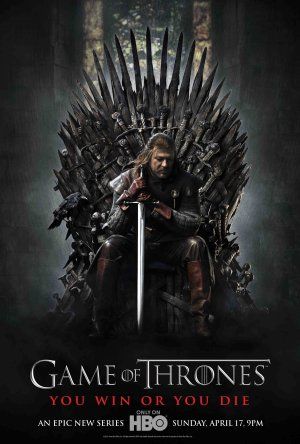

Take, as examples, the pilot episodes of “Firefly,” “Game of Thrones” and “Warehouse 13.” Five minutes into “Firefly”’s “Serenity,” the viewer knows from the setting, costumes, dialogue and music that the series is a Space Western. “Game of Thrones’” “Winter Is Coming” similarly frames the show as high fantasy, although its first scenes, which involve a mysterious massacre, a reanimated corpse and a terrifying shadowy figure, mislead the viewer with traces of horror and paranormal themes. “Warehouse 13”’s “Pilot,” on the other hand, dithers. It suggests supernatural intrigue in its opening but then hides it beneath a Secret Service investigation in an attempt to build tension. Its exaggeratedly mystical ending— the prevention of a magical cult’s human sacrifice— is at odds with the relatively normal investigation and makes the genre of the show unclear.

Excellent pacing in a pilot means that the viewer never feels bored. There should be no empty space; every moment must advance the plot. The first episode cannot afford to dwell on particular moments with particular characters, because the audience does not yet know the characters or issues in the show well enough to care. Time wasted on fluff causes the audience’s interest to dwindle.

Again, “Firefly’”s pilot is a superlative example, “Game of Thrones’” is a modest one and “Warehouse 13”’s is a failure. “Serenity” opens with action— a battle’s climax— and never tones down the intensity. Every scene develops a new problem or contributes to a resolution. Even the quiet scenes are packed with energy, as when the Serenity’s crew steals cargo from wreckage while an Alliance military ship passes dangerously close by.

“Pilot,” in contrast, drags on painfully. Protagonists Pete and Myka spend far too much time bewildered by puzzles with simple answers. They scratch their heads over their transfer to “Warehouse 13” and amble aimlessly through their investigation, not certain whether they are following real leads or not. “Winter Is Coming,” though never so dull, only occasionally matches the intensity of “Serenity.”

Attention to plot is sometimes sacrificed to show off costume and set designs, to set up story threads that will not be fully addressed until later and to dwell on recently introduced characters.

Character introduction is a delicate issue. The best pilots engage the audience’s curiosity about characters while limiting exposition. Backstories should never appear in the first episode unless they are crucial to progressing the plot. Far better to present an alluring enigma than to expose too much, too soon.

“Firefly” performs excellently in this area, giving and withholding exposition with a precise hand. Consider, for example, Simon Tam, a passenger on the Serenity. Simon’s story appears to come out when the captain discovers that Simon has smuggled a girl aboard and Simon must explain that she is his sister, whom he is hiding away from the government school that was experimenting on her. Simon’s explanation disguises problem creation as exposition. Why would the government want River Tam? What did its experiments do to her? These questions prevent Simon’s story from satisfying the audience’s curiosity, serving only to tantalize them.

“Game of Thrones” has some difficulty because it boasts an enormous cast of characters, many of whom need to be present in pilot scenes for later episodes to make sense.

To compromise between attempting too many introductions and failing to let characters appear where they need to, “Winter Is Coming” simply ignores some of the people in a scene, putting off revealing their roles until a more appropriate time. This does cause annoyance when a face recurs several times without an associated name, but is otherwise a solid solution.

The only fault in “Warehouse 13” is its introduction of characters with stereotypes. “Pilot” continually presents Pete and Myka as opposites; Pete is the impulsive, light-hearted partner whose strength is instinctual, whereas Myka is the cautious, uptight partner who plays by the rules. It tries to mitigate the superficiality of their roles by weighing them down with backstories, but only worsens the awkward cliché.

A pilot may not perfectly reflect the subsequent episodes, but it is indicative of the ability to draw in viewers through strong writing and characters. For those who favor excellence of plot and dialogue over excellent acting, the pilot is a good gauge of a show’s promise.