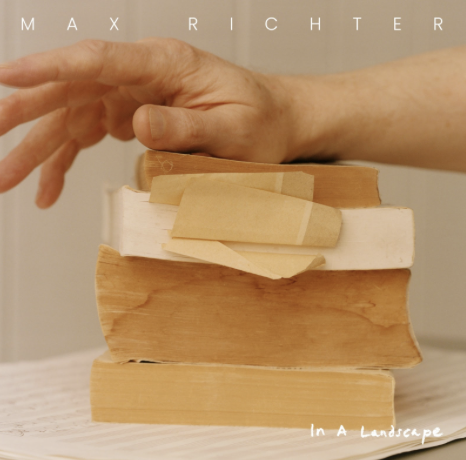

In reading about and listening to various music genres throughout my life, I have reached one fairly concrete certitude: music cannot exist on its own. What matters most is context. Space, environment, company, experience and other factors play a role in the way we hear a piece and, more importantly, the way it connects with us. In the age of audio recording, this idea seems to be lost. Albums are pushed in hopes of creating a universal experience with a meaning that appeals to a large audience. What artists fail to recognize, however, is that the audience drives the meaning of the music. Max Richter explores this idea in the album “In a Landscape.”

In an interview with Zane Lowe of Apple Music, Richter rests his computer on a desk that displays the newly built studio used in the mixing and mastering of “In a Landscape.” Immediately, Lowe notices the presence of windows, typically absent from recording studios due to their reflection of sound waves. Richter explains that he wanted to create in a place that inspired the ideas that he hoped to display on the album. He embraced the natural light and intrusion of sound from the outside world. The new studio, Richter describes, provided him with a new journey, one littered with “experiments” and fruitful in its “discovery.”

The word “journey” would fall flat if being used to describe “In A Landscape.” A journey implies a beginning and an end, with some degree of plot or action in between those two points. Instead, I would describe “In A Landscape” as a circular observation. There is no plot or cohesive story, rather, the album consists of a series of commentaries on the human condition as it stands presently. Through this, Richter takes a step back and leaves a large portion of the responsibility to the audience. The listening experience is dependent not on the quality of headphones it is experienced through, but the situation in which the listener finds themselves when hearing it. One who listens from a bench overlooking a pond on a quiet, overcast Sunday afternoon will come away from the album with much different observations than one who listens to it in their car in rush hour traffic after a day at work. It is in this way that the experience takes a circular path — starting and returning at a similar place, but leaving the listener changed in their perspective of the world that surrounds them.

In order to achieve this, Richter blurs the lines between natural and electronic, a reflection of a division ceasing to exist before our own eyes. Richter’s first piece on “In A Landscape,” “They Will Shade Us With Their Wings,” paints a picture of a world that once was. Through a contrast of strings in both the upper and lower register, Richter’s ambient introduction provides a peaceful space to reflect. Immediately following, however, this space is ruptured by the first of what Richter calls a “Life Study.” To put it simply, the sounds of shoes clattering on gravel, with an electronic drone transporting listeners back to the present or even towards the future. It may seem unnecessary to strip listeners of a much needed meditative space, but Richter uses this change as an opportunity to display the constant tugging of our mind from electronic and physical realities. This tussle between natural and artificial continues throughout the next few pieces, with “Life Studies” scattered between to provide glimpses into the world we have grown to accept without question.

It is not until “Only Silent Words” that a major shift in ideas occurs. Playing with the expectations of listeners, Richter unveils an entirely electronic piece that is reminiscent in many ways of the work of Floating Points or other pioneering electronic producers. Being thrown completely off guard, the listener is forced to focus in order to regain their footing. The electronic drones provide an almost comforting oasis from the unfamiliar classical instruments displayed earlier in the album. However, almost as if it never happened at all, the piece that follows, “Late and Soon,” leads listeners back to the natural world through the use of somber strings that land deep in the lower register.

The listener is not treated to another electronic refuge throughout the rest of the work. The remainder of the pieces (including the “Life Studies” songs) consist mainly of classical ideas and concepts, albeit with an innovative and modern twist. The album concludes with two pieces that send home the concept of shift and alternation between ways of life. The first, “Love Song (After JE),” begins with a dark chord progression on the piano that is quickly accompanied by strings that match the depressing mood. Seeming to be the penultimate piece, the listener is left on the edge of their seat (far away now from the meditative space that was introduced to begin the album), waiting for a resolution to the dissonance that plagues the music. It is not until the final piece, “Movement, Before All Flowers,” that this resolution is finally reached. The listener is transported completely away from the chaotic electronic concepts to a serene environment that they are free to grace through, accompanied by strings that provide a hopeful and introspective conclusion.

With “In A Landscape,” Richter hopes to take attention away from the music, instead shining the spotlight on the listener and their ability to comprehend the nature of the life they now find themselves in. It is clear, though, that Richter has hope for a future in which the public is able to subconsciously connect with both the authentic and contrived aspects of life.