Lazarus Nazario On The Therapeutic Power of Artwork

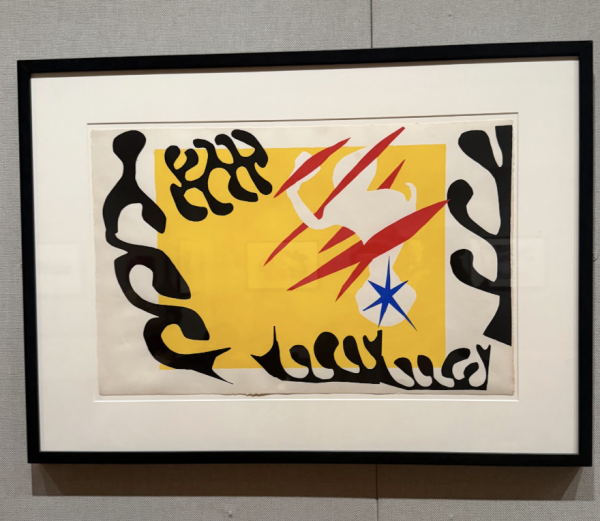

Nazario’s painting “Screengrab” was inspired by an image of a young suicide bomber whose mission was thwarted. (Courtesy of Lazarus Nazario)

When Lazarus Nazario was told she had a 2% chance of having a “take-home baby,” she was crushed. What would she leave behind in the world? Her answer, she decided, was her artwork.

Nazario is a Bronx-based sociopolitical artist who works in paint and multimedia. She was born in 1968 in Staten Island, NY. As a second-generation Puerto Rican, also called a Nuyorican being from New York, Nazario experienced racism from a very young age. She was harassed and called slurs at school but struggled with the fact that she couldn’t speak Spanish at home. “I’m not Puerto Rican enough for some people, but I’m too Puerto Rican for others, so somehow I didn’t fit in either place,” she said. Nazario’s artwork draws inspiration from the culture and history of Puerto Rico, her experiences with racism and her personal struggles.

Growing up, Nazario was an incredible singer, and she always thought she was going to end up being a singer-songwriter. But in 1991, when she watched a television program with Leon Golub and read a biography of Frida Khalo, a light was ignited inside her to pursue art. She said, “That’s it. I’m a painter. This is what I’m supposed to be doing.” Nazario’s horrible stage fright disappeared the day she decided she wanted to be a painter. “It didn’t matter anymore, I could sing in front of anyone,” she said.

Nazario explains, “Something I think is kind of interesting about painting is that it’s something I can do in my room. I can go through my feelings and everything else I have to go through to get that out, but then it’s out and I can put it on a wall.” She says she doesn’t get nervous at openings because she already worked through all the hard parts.

Creating artwork has always been therapeutic for Nazario. When she was told she wouldn’t be able to have kids, something she had always wanted, she used her painting to work through all the feelings and emotions that came with that life-changing news. At the same time, she was researching female suicide bombers in the Iraq war for a grant for the George Sugarman Foundation. Her husband at the time sent her a series of screen-grabs which showed a young suicide bomber whose mission was thwarted. Her arms were burning, and she was tossing and screaming. The photos struck Nazario. “Those two things, her dream of martyrdom and my dream of motherhood, collided,” she said. She was inspired to create paintings based on the images and the result was “The Shattering,” and “Screengrab.”

Nazario said, “I didn’t care, I did not give a f—, it was a moment where I was like that’s it, all bets are off, I’m making what I want to make. If it’s gory, it’s gory. I don’t care; this is what needs to come out.”

The moment when Nazario created “The Shattering” and “Screengrab” solidified her own understanding of her work’s legacy. She sees her work as her imprint on the world. “My mantra is just make the work,” she said. “Wherever it goes or who buys it or who doesn’t buy it, just make the work, it will be here after me.”

These two paintings also allowed Nazario to define her work. She explained how she realized it was okay to be gory, as long as it was in the name of religion. This new mindset allowed her to “hijack” or repurpose the idea of devotional art in her own work. Nazario doesn’t shy away from violence in her work, but at the same time, many of her pieces are very peaceful. Her body of work shows the many sides of life.

Nazario recently had to move to Pittsburgh when her apartment in the Bronx was sold, but she will return to New York as soon as she can to resume work on a large multimedia altarpiece, which is currently in storage. The piece is inspired by Van Eyck’s “Ghent Altarpiece” and Van Der Heyden’s “The Last Judgement.” It is a historical painting that will feature members of her family and tell their story about coming to New York from Puerto Rico. She hopes to see it in a museum one day.

Despite the unexpected move, Nazario is making the most of her situation. She goes down to a river every day, filling small thumbnail sketchbooks and she continues to paint and make work. “I have to keep making work or it’s no good. I can’t live. I can’t breathe,” she said. Anytime Nazario feels anxious, she just has to start to mix paint. “It all goes away in 10 minutes, maybe 12 minutes.,” she said, “It’s the strangest thing, it’s like a meditation. Work for me is a meditation. It rights the ship.”

Ava Erickson is a senior from Denver. Her passion for writing and language led her to double major in journalism and Spanish studies. She began working...