By PJ BROGAN

COPY EDITOR

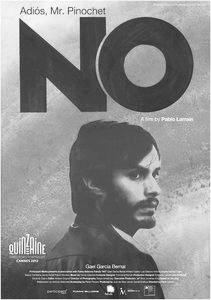

Amour got all the buzz—and the Academy Award for Foreign Language Film but there were in fact other foreign movies released in 2012. One such picture was the simultaneously happy and bleak Chilean film No, a movie which was also nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars. This Spanish-language drama, directed by Pablo Larraín, follows the events of the 1988 Chilean National Plebiscite, which ultimately led to the ouster of the brutal Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. The people of Chile were given the decision to vote “Yes” to keep Pinochet or “No” to reject the dictator and create the beginnings of a new democracy. It is the kind of setting that easily lends itself to hard-edged, dramatic political espionage like John Frankenheimer’s classic suspense tale of a fictional US military coup in Seven Days in May or to biopics of great men and women faced with great decisions a la Steven Spielberg’s saintly portrayal of our 16th president in Lincoln.

Amour got all the buzz—and the Academy Award for Foreign Language Film but there were in fact other foreign movies released in 2012. One such picture was the simultaneously happy and bleak Chilean film No, a movie which was also nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars. This Spanish-language drama, directed by Pablo Larraín, follows the events of the 1988 Chilean National Plebiscite, which ultimately led to the ouster of the brutal Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. The people of Chile were given the decision to vote “Yes” to keep Pinochet or “No” to reject the dictator and create the beginnings of a new democracy. It is the kind of setting that easily lends itself to hard-edged, dramatic political espionage like John Frankenheimer’s classic suspense tale of a fictional US military coup in Seven Days in May or to biopics of great men and women faced with great decisions a la Steven Spielberg’s saintly portrayal of our 16th president in Lincoln.

Larraín, however, goes a different route. The referendum itself was preceded by about a month of television commercials advocating both for and against Pinochet and No follows TV ad director René Saavedra played by Gael García Bernal (Y Tu Mamá También) and his band of rogue, left-wing filmmakers that made the commercials for the “No” campaign. Instead of sanctifying these men and the country’s ensuing democracy, Larraín tells an honest story of whitewashing and corrupted idealism in the creation of a modern democracy.

Pinochet’s government was economically beneficial for the middle and upper classes, but thousands of political dissidents were suppressed under his regime. In his 2006 obituary, The New York Times stated that more than 3,200 men and women were murdered during the Chilean ruler’s 17 year stay in power. However, the “no” or anti-Pinochet commercial makers, when creating their 15 minute television spots, elect not to include these terrible deaths, and instead they filled their TV time with blind optimism and promises of continued success for the wealthy. Sunshine and rainbows were a repeated theme throughout the advertisements. It seems like an absurd and borderline offensive campaign, but it worked. Pinochet was voted out with 53 percent of the vote, and Chile could celebrate the birth of a democracy without fully confronting its past.

Saavedra is a rather stoic figure, but Bernal plays him with enough subtlety and heart that he is a very likable figure. A fondness for toy trains endeared him to me (I was an avid Thomas the Tank Engine fan in my childhood). He knows the human cost of the Pinochet regime his ex-wife has been the victim of several attacks while protesting his rule but he masterminds the “No”s wide-eyed and simplistic campaign, knowing that the people do not want to be confronted with the truth. By the film’s end, he almost seems hurt that his advertisements have worked, and that people could be more easily turned by a well-packaged lie instead of the cold truth.

No sets itself up as a counterpoint to another film well-represented on Oscar night: Lincoln. Both films tackle a celebratory moment in their respective nations’ history, but treat them very differently. Lincoln as beautifully shot and acted as it undoubtedly was—just about pretended that Abraham Lincoln single handedly destroyed all racism that would ever exist in America. No, on the other hand, asks us to consider that there are potentially problems and diseases underlying even the greatest moments in a country’s history. It is an interesting, and important, argument, and one well worth checking out. If you like to read and think about your movies, No is well worth your money.