“Parasite” Skillfully Combines Comedy and Thrill

In Bong Joon Ho’s “Parasite,” nobody comes out clean. It’s a movie of goofy circumstances transformed midway through into a tragic thriller. Director Bong brutally keeps the camera rolling as every character becomes dirtied in the mad rush for money, slave to the cash rules of working life and the dog-eat-dog principles of capitalistic society. It is a statement for the present time.

The film is set in Seoul, South Korea, and begins with images of squalid family life. The Kims are grasping at loose ends. Father Kim Ki-taek, a former valet, mother Chung-sook, artistically-talented but unmotivated daughter Ki-jeong and son Ki-woo (respectively, Song Kang-ho, Jang Hye-jin, Park So-dam and Choi Woo-shik) live together in a slum-house without internet and without space, all of them out of work, reduced to folding pizza boxes to sell back for much-needed cash.

The movie kicks into motion when a friend of Ki-woo asks him to take over the tutoring of a wealthy teenage girl while he goes off to study abroad. Ki-woo accepts, and the next day interviews for the job, walking up the steps of a sleekly modern mansion complete with housekeeper and well-irrigated lawn, a bright, roomy, neatly organized residence that could not be more different from his own home.

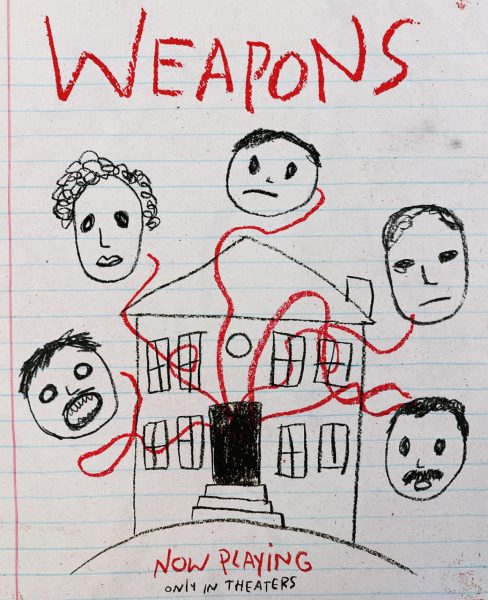

We’re introduced to young Da-hye (Jung Ji-so), a mediocre but rich student who instantly falls for her new tutor, her brother Da-song, a rambunctious 10-year-old who draws messy portraits, and her mother, Mrs. Park (Cho Yeo-jeong).

Bong wastes no time giving the audience the impression of a ditzy, out-of-touch, blandly pretty housewife in Mrs. Park, an old trope that soon becomes predictable. Mrs. Park is easily impressed by Ki-woo’s faked university records and nonsensical academic advice (“An exam is like a jungle,” he says), and he lands the job.

On his way out, he looks at some of Da-song’s portraits with Mrs. Park, who laments over the kid not having an adequate guide for his artistic endeavors. Ki-woo’s eyebrows raise: “I know an art student who would be perfect for your son.” The next day, his sister Ki-jeong is working for the Parks, under an assumed name, pretending to have no relationship to Ki-woo. After that, the siblings dupe Mr. Park(Lee Sun-kyun) into firing his driver and contracting their disguised father instead, and then they get rid of the housekeeper, replacing her with their mother.

“Parasite” becomes a tale of two families superimposed on top of each other, one serving, the other served. But if this symbiosis doesn’t seem mutual, Bong makes sure to include scenes of a harried Mrs. Park trying her own hand at dish-washing and food-making after sacking the first housekeeper, the pretty housewife in over her head. If this is a movie about parasites, then the lasting point is that they’re to be found on both sides.

The first half of the movie veers towards comedy, making great fun out of the elaborate maneuvers that the Kim family takes in putting the wool over their rich benefactors, highlighting the absurdity of arrangements and endlessly poking fun at the vacuity of the wealthy.

Bong loves to provoke laughter with spacey blandishments of Mr. and Mrs. Park, mocking their false projection of Basquiat-esque genius onto the untalented Da-song. This culminates in a hilarious sequence where the two discuss the discovery of a pair of panties left in the backseat of Mr. Park’s chauffeured limousine, speculating over the sexual improprieties of the driver. “Why couldn’t he do it in his own seat?” Mr. Park wails with a straight face.

The fun is such that one accepts the con and starts rooting for the Kims, relishing in their happiness and almost forgetting who they had to push out in order to set themselves up.

This in mind, it’s a testament to the director’s cruelty and perversity how effectively he redirects the plot from charmed comedy to eerie mystery, leading rapidly to a bloody finale. The Kims decide to spend a rainy evening in modern luxury when the Parks go on a birthday camping-trip for their son, only to be interrupted in the middle of their house-squatting by the ring of the doorbell.

It’s the old housekeeper Moon-kwang (Lee Jung-eun), and as the camera closes in on her puffed-up, rain-streaked face, she gives the screen an unsteady polite smile that keeps pleading, desperately, to be let in: She needs to retrieve something she “left behind.” The comedy of the destitute and the rich is transformed into a quasi-horror film.

The best parts of the film are in this unpredictable, twisting descentinto violence, which only mounts in intensity. Everybody bleeds and no impulse is presumed to be innocent. Bong digs deep in his effort to show lack of pure intentions, criticizing relationships of economic dependence that only preserves the likability of its cast of characters by making them all suffer equally.

The idea is hip enough to touch any modern audience, who’ve come to the movie theater from a society where capitalism has run rampant in some ways. But because of this, beneath the thrill of the whirling malaise that Bong injects into his fable, the film hardly shows us anything we haven’t seen already.