By JAKE KRING-SCHREIFELS

Staff WRITER

Everything about Alexander Payne’s Nebraska feels authentic. You can feel it in the desolate Midwestern towns and their soft spoken residents. You can feel it in the empty, blue-collar roads and in the handful of elders that camp in Main Street’s neighboring bars and steakhouse. You can feel it in the lingering landscapes, the frames of infinite flatness — like the picturesque Hawaiian tropical sunsets in Payne’s last film The Descendants — that just sit there waiting for you to get acquainted to the setting.

The director is from Omaha, and there is a reverence and love that goes into his portrait of his state, his people and their tired, dusty life. Payne knows how to capture people and places with such ease because he gets the small things right. He also does not patronize. He makes his subjects characters, who in other hands would come off as caricatures. The only reason you might feel like some fit into the latter category is because most of their daily lives are so one-dimensional.

Contrary to the title, the movie starts in Billings, Mont., where Woody Grant, played intrepidly by Bruce Dern (Monster), stubbornly attempts to walk to Lincoln, Neb. to collect a million-dollar sweepstakes. The prize is a magazine fraud but Woody persists, with an odd mixture of senility and headstrong persistence to claim it. As a result, his son David (a solemn Will Forte) must track him down in his Subaru each day and escort him back to his shrewish wife Kate (June Squib). To end the arguing, David drives his dad to Lincoln for some father-son bonding. He knows the million dollars is a gimmick, but wants Woody to pursue something before Kate anxiously puts her husband in a nursing home.

One also gets the sense that David wants to make this trip for himself, too. He has just broken up with his girlfriend of two years, works at an electronics store and his indoor plants are dead. His brother Ross (Bob Odenkirk) is on the road to success, so Nebraska becomes a beacon to escape a lonely existence, to earn some pride en route to collect a scam. You also get the sense David wants to reestablish a relationship with his war-vet father, to heal some buried, drunken home-life wounds. His attempts mostly fall on Woody’s partially deaf ears. “C’mon, have a beer with your old man. Be somebody.” David must oblige.

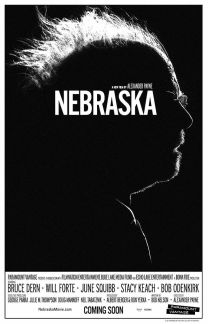

The film was shot in color and then formatted into black and white. It is a fitting scheme, considering the town and its composition of people that feel like they have been collecting dust in some old photo album. This little population feels so cut off from society, isolated from outside culture except for the rusted Coors Light window neons and communal television gatherings. Payne is careful not to mock this insular lifestyle, though. This is more small-town celebration than condescension.

Woody coasts through all of this without a lot of thought, but there is tenderness in his brusque fathering; He is refreshing even as he stubbornly waddles along. There is no sex in the movie except for when Kate flashes her relatives’ gravestones — and there is no violence besides David throwing a nice right punch. This is just regular life in all of its frustration and patience and love. Sometimes movies make us forget what that is. Lucky, we have Payne to remind us.