Just a few blocks from Fordham University’s Rose Hill campus, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) of the mid-1970s used a modest storefront as their home office for a large-scale fundraising campaign to support Irish-Catholic liberation in Northern Ireland. In a 1975 New York Times article, the funds raised by the Bronx office location were linked to arms procurement initiatives for the IRA in their fight against loyalist oppression and opposition in a conflict known as “the Troubles.” “The Troubles” refers to the religious, ethnic, and nationalist conflict between Protestant loyalists and Catholic nationalists in Northern Ireland throughout the second half of the 20th century. It was a time fraught with confusion, violence, and intense political convictions that left relatively few citizens of the small nation unscathed. While the conflict is said to have officially ended with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, historians argue that much of the conflict’s damage remains unaccounted for. This lack of accountability is due to a number of factors, not the least of which is the nature of mystery and secrecy surrounding the prominent paramilitary forces that drove the worst of the conflict’s fighting.

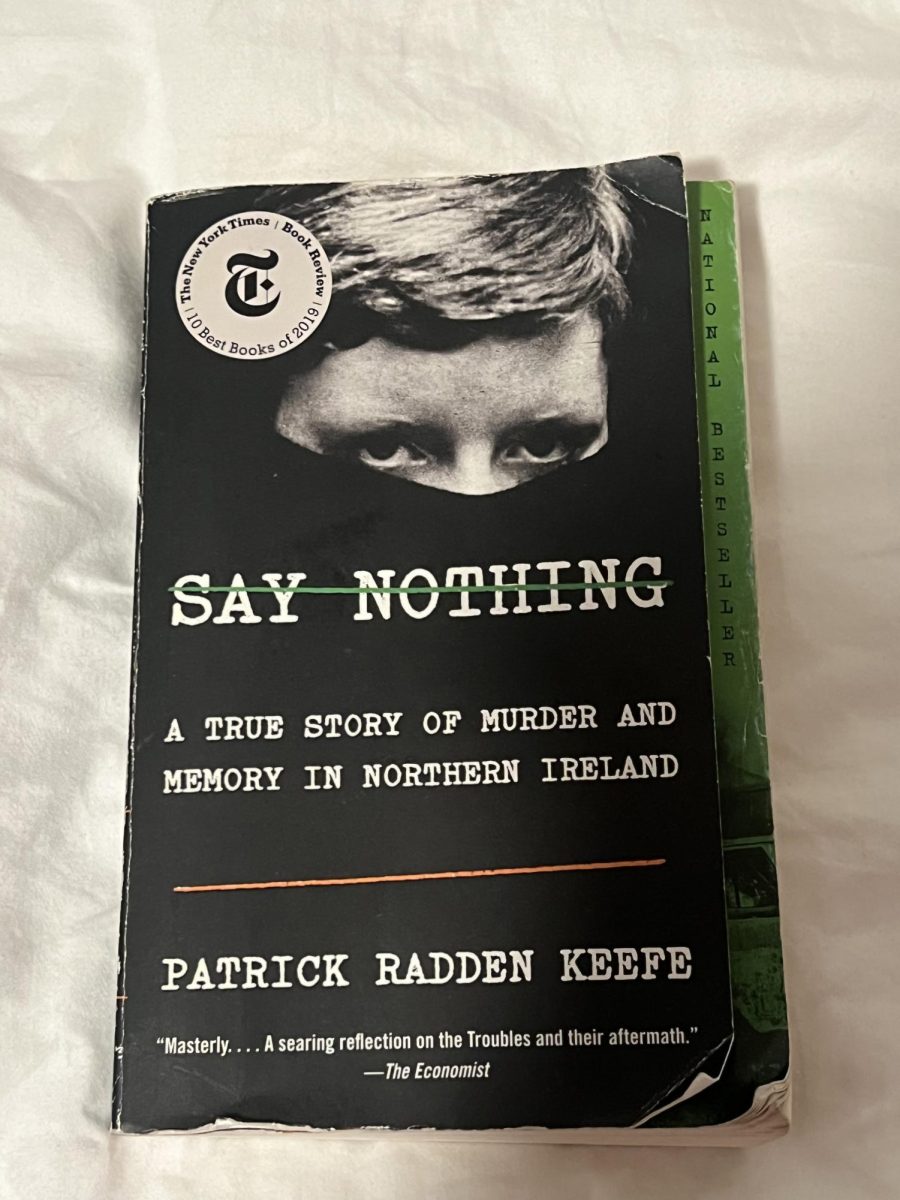

Patrick Radden Keefe confronts, explores, and utilizes this air of secrecy in his novel about the Troubles, “Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland.” The dynamic historical text delves right into the thick of the conflict’s mystery by focusing on the unsolved murder of Jean McConville, a single mother of 10ten, who was kidnapped from the family’s Belfast apartment in 1972. The case is just one of several murders and disappearances from the Troubles that remain unsolved, and Keefe’s speculation about what may have happened to McConville drives the book’s composition.

Although written a few years ago now, the novel remains as relevant as the Troubles themselves. The conflict continues to bleed into the modern world as scholars and citizens alike wonder what can be done to further resolve tensions. As things stand, Northern Ireland is still heavily segregated, and cities like Belfast still harbor physical scars of the conflict in the form of decades-old “peace walls” separating Catholic areas from Protestant ones. The New Humanist reported in late 2023 that about 90% of children in Northern Ireland still attended religiously segregated schools. So while the Good Friday Agreement secured a certain peace between paramilitary groups, the religious tensions underlying the Troubles linger.

Keefe chronicles the conflict through a series of interlocking vignettes, drafting a road map of sorts through the leadership of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), also called the Provos. This style provides a provocative and compelling narrative that encourages readers to become emotionally invested in the complicated histories of the individual players involved in the conflict. IRA members of note featured in the novel include Gerry Adams, an IRA leader turned politician who worked diligently to cover up his past involvement in the paramilitary group, and the infamous Price sisters, Dolours and Marian. Dolours Price in particular stands out as a remarkable character in both the text and the history of the Troubles itself. After being attacked by off-duty members of the Ulster Special Constabulary, a police force for Northern Ireland, at a peaceful civil rights march, Price and her sister were radicalized and joined the Provos. From there, Dolours would go on to orchestrate car bombings, assassinations, and a traumatic 208-day hunger strike in which she and her sister were force-fed while incarcerated.

Stories like Dolours’s are key to Keefe’s attention-grabbing writing strategy. Keefe’s breaking down of the Troubles into these smaller stories also makes the history of the period easier to digest as it scales down major themes into specific details that paint a broader picture of the conflict. His discussion of the major IRA players at the time naturally leads Keefe to connections between IRA leaders and their loyalist counterparts in the Ulster Defense Association, an umbrella paramilitary group that organized and endorsed anti-Catholic terrorism in Northern Ireland.

“Say Nothing” is an incredibly compelling novel primarily because the Troubles have such a dramatic history. In his writing, Keefe has no need to sensationalize because his content was already sensational. From car bombs and secret trips to London to double-agent espionage and hunger strikes, Keefe writes about events and people that were themselves outlandish. “Say Nothing,” does, however, tell a very complicated history, and Keefe needed a way to tell that story without losing the plot of it. He does this by focusing on Jean McConville’s death as a through-line, which conveys the dramatic and tragic nature of the Troubles without further complicating the conflict. This is an especially important literary tactic for non-Irish readers, whose prior knowledge of the conflict may range from little to none. As such, “Say Nothing” serves as a wonderful jumping-off point for contemporary readers interested in learning more about the Troubles and about the fraught history of Ireland in general.