Ireland, though I’ve yet to visit, has given me some of the richest tales and lyrics of my adolescence. I may have consumed “Normal People,” “Derry Girls,” “Wasteland, Baby!” and “Angela’s Ashes” for the first time in high school, but they always have a slot reserved on my rotation today.

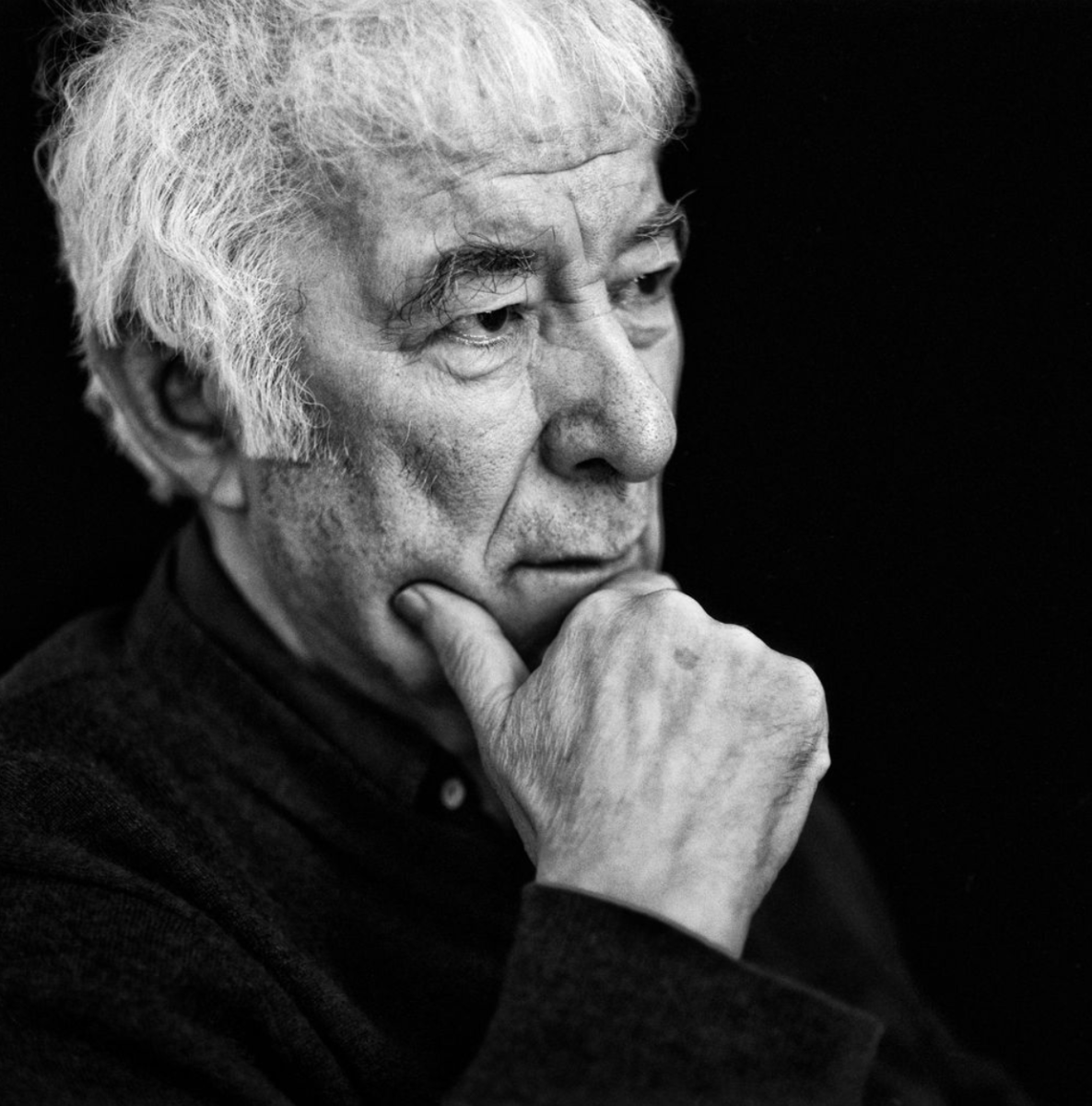

Spring of my senior year of high school, I ordered Seamus Heaney’s “Death of a Naturalist” to write about for a paper. I’d read a random selection of Heaney’s poems for class, but in a fit of poetic purity, I decided I could not read anymore if they were out of the order that Heaney intended. When the collection arrived, I unpacked it carefully, the card-sized, salmon-pink volume feeling like a thin leaf in my hands.

With the book in hand, I sunk my teeth in. On the subway, on my bed, at my desk. Lines ran across the page like clear water, and I savored every sip. For all his candor and clear imagery, Heaney wrote with such a richness in line that I couldn’t help but get stuck on. I would read a line, then again, running it in my mind over and over like I was working a cough drop.

No longer strictly linear and narrative, words became noise, became motion, became voice within the technicolor modicum of a poem. It was something sweet and bitter, warm and cold, to be swallowed and to be swallowed whole by.

I could not, no matter how hard I’d try, spell out just how much Heaney’s work has consumed me and my writing ever since. That summer, I went out and bought every one of his works I could get my hands on. After “Death of a Naturalist,” I made it through “North” and got started on “Electric Light.” The whole set moved in with me to college, where the spines stood across from me on my desk like a set of trees. And every time I’d read, I’d find a well-placed word for where I was at the time.

“Death of a Naturalist” was Heaney’s debut collection about his childhood in County Derry. As Heaney wrote out his own upbringing with utmost care and precision, I mused on mine, which I was all too eager to get away from. In all the tension and adrenaline of becoming an adult, Heaney told me to keep my feet planted even as I moved away.

As I moved to “North,” I was thrust into a rich Irish history and forced to get my bearings quickly. Poring over the Troubles, I worked to unfold the thick cloak of references and sorrow laid out before me and became a better reader in the process. Aislings and peat bogs began as strangers to me but became people, alive in Heaney’s palms by the closing of North. I stood with him in colonial confusion at the foot of the Atlantic in “North” and took the Viking’s invitation alongside him with resolve.

At every moment, I cannot thank the Irish voice enough for meeting me in the nightly quiet of my bedroom, reminding me of all the things that fall between the gaps: the goodness of dirt, the value in work done by hand, the need of a set of shoulders next to your own.

Perhaps most importantly, it urged me to write more myself. In four-lined stanzas and paragraph verse, Heaney made me think twice about the squat pen in my hands. What was it doing — capped and horizontal, only opened for the occasional annotation?

His conviction for the pen’s place in his hand had me hunger for it on my own.