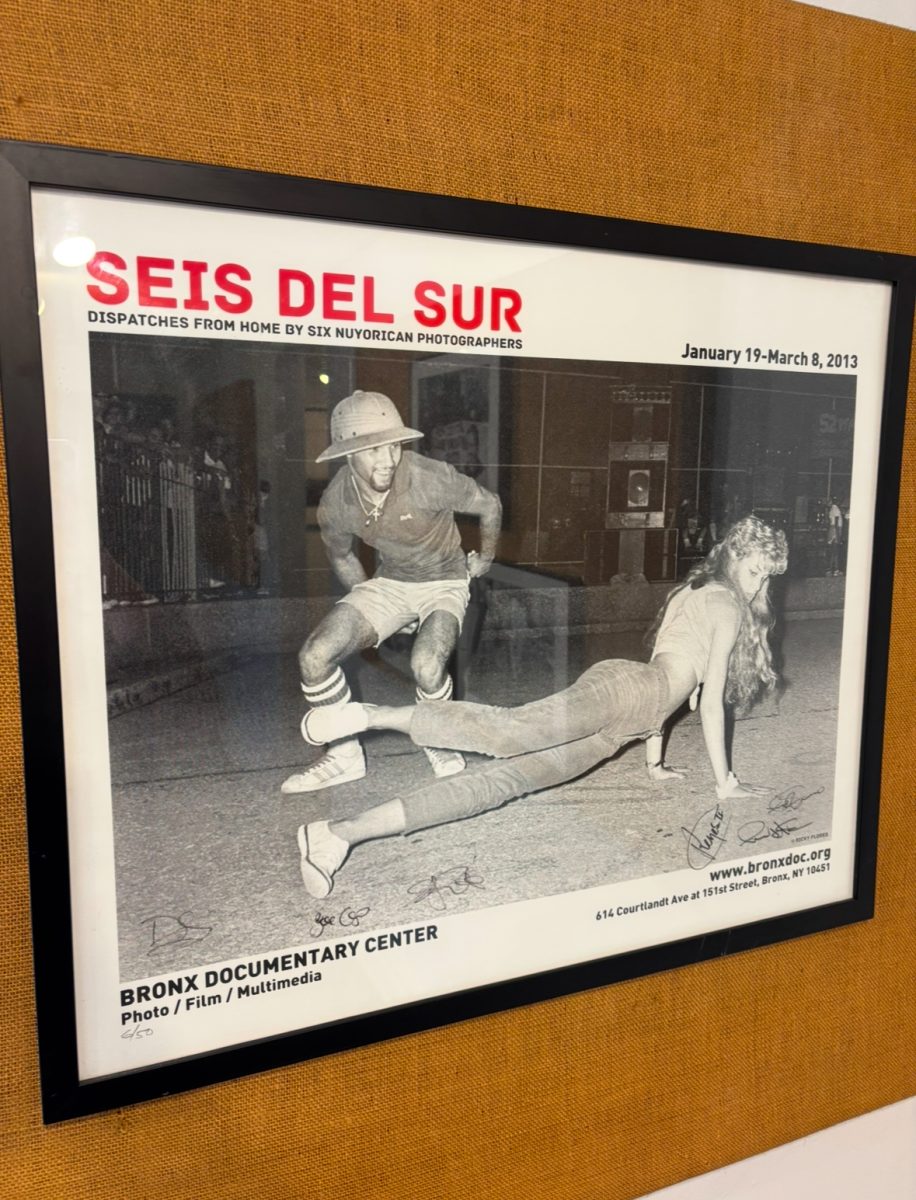

Located at the Museum of Bronx History, a quaint, historic brick house on Bainbridge Ave just 20 minutes north of Rose Hill via the Bx34, the Seis del Sur exhibit is small but powerful. It combines the work of “los seis,” a group of six Puerto Rican photojournalists from the South Bronx — Joe Conzo Jr., Ricky Flores, Angel Franco, Edwin Pagán, David González and Francisco Molina Reyes II. These men grew up in a period of rapid change, and, in many ways, deep turmoil in the Bronx.

One example of this turmoil highlighted in the photographs at the exhibit is the fires that ravaged the Bronx during the 1970s. Due to the fiscal crisis of the decade, redlined districts saw disinvestment in city services like firefighting. Six fire companies in the South Bronx closed, and many others were reduced in size. Fires started either from landlords burning their buildings for insurance money or from “lack of upkeep,” such as “a spark from faulty wiring” or “a gas leak.” Given the city’s stripping of resources to deal with fires, they spread quickly and caused intense damage — 80% of housing was destroyed and 250,000 people were displaced.

The fires were largely due to racist redlining policies, which marked areas inhabited by a majority of people of color as “hazardous.” These not so natural disasters illuminate the history of neglect, defunding and stereotyping experienced by people in the South Bronx.

“The Bronx was burnt. Drugs were rampant. Gangs were rampant,” said Conzo Jr. about growing up during the Bronx fires. Flores added, “Building after building, block after block began disappearing.” Gonzalez remembered, “I grew up always smelling wood burning, metal burning. It was a part of the atmosphere, you would always hear firetrucks zooming by at all hours of the night.”

One of the photos featured in the exhibit, “Rubble” by Carmen Mojica, shows some of the destruction the fires caused: abandoned buildings, some of them left halfway standing, others burned all the way to the ground, scraps of various materials spread everywhere and people left to pick up the scraps. Mojica would pass by these sights everyday when dropping her daughter off at daycare, and others like them were all too common in the years after the fires.

In Ricky Flores’ 1983 photograph “Building Decals on Fox. South Bronx,” two men stand outside an abandoned building with decals to cover up broken windows “so that it wouldn’t upset the commuters on the Bruckner, probably the very owners of the abandoned properties.” It appears to be a cold day outside. One man stands with his hands clasped together, the other stands slightly behind looking as if he is trying to hold in laughter. The photo is accompanied by the caption, “We lived in a time of murderous absurdities.”

In some ways, it would be easy to end the narrative here. The Bronx has a history of struggle, the end. However, los seis are not content with such an oversimplification. Without shying away from the defunding, discrimination and lack of resources Bronx communities face, they emphasize how these struggles strengthened community ties and led to action against injustice.

Francisco Molina Reyes II commented about this period in Bronx history: “It was an amazing time to be there. It was one of the worst times but one of the best times because there was so much going on in terms of awareness, consciousness, movement and the regeneration of youth.”

And everything being experienced was being experienced together. Conzo said that in the midst of a whole lot of destruction, “The community aspect was really tight. You didn’t go a day without food because if you didn’t have food, Doña Flora next door was cooking enough to feed you and your brothers and sisters and Doña Carmen upstairs.”

He shows the tightness of the community in his 1978 photo, “Lot Cleanup at United Bronx Parents,” in which everyone worked together to clean up an area of rubble.

A strong sense of community in the Bronx meant that people looked out for each other, not just for themselves. And when one member of the community was hurting, everyone would rally around that person, seeking change when necessary.

Pagán’s photo, “Anthony Baez” depicts two women marching in a late December 1994 rally against police brutality, holding a sign with the name of its most recent victim. 29 year-old Anthony R. Baez was home for the holidays spending time with his family. While tossing a football with his brothers outside Cameron Place, they accidentally hit the side of a police car. This provoked Officer Francis Lavoti, and in the altercation that followed, Báez (who had asthma) died as the result of an illegal choke hold. The photo highlights how the community came together to protest in the spirit of each person being responsible for their neighbor.

The historias exhibit shows us that the best stories never end with the individual or pretend that the struggle is where the story ends. Instead, the best stories bring into focus the community and serve as a reminder that there is always hope in difficult times, mostly in the act of being together.

The photographs of los seis visually preserve the authentic history of communities. They personalize the physical spaces that many people would overlook by highlighting what they mean to the communities they serve. They debunk the stories told by people who are far away from the communities themselves and tell new ones instead from up close. Other people don’t get to decide what kind of place the Bronx is or what kind of people Bronxites are. These historias are for members of the Bronx community like los seis to tell and for the rest of us to listen to.

If you want to experience las historias, it’s definitely worth it to go see them for yourself. Jan. 26 was originally the final day of the exhibit’s showing, but due to popular demand, it has been extended until April. More information about los seis and their photos can be found on the Seis del Sur website.