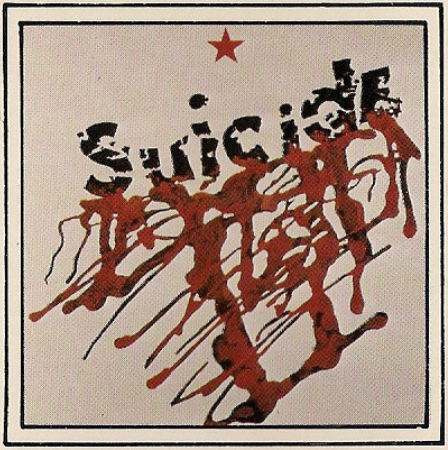

Suicide’s Pioneering Proto-Electronica

Suicide, an early electronic duo composed of singer Alan Vega and instrumentalist Martin Rev, refused to fall victim to this dulling effect.

By Adam Payne-Reichert

Studio recordings can often be unfortunately sanitizing. When listening to the sun-faded guitar riffs of The Velvet Underground’s “Sunday Morning,” for instance, it is easy to forget that Variety described the band’s performances as “a three-ring psychosis that assaults the senses with the sights and sounds of the total environment syndrome.”

This effect may be caused by a number of disconnects between the music’s studio and live iterations. First, recordings from decades ago can sound tame because contemporary listeners don’t have a full sense of how revolutionary the music was for its time.

Second, due to the difference between studio recordings’ portability and live performances’ all-encompassing experientiality, studio versions often allow a bit of distance from the emotion and reaction the music was initially intended to provoke. There’s also the lack of a crowd. Listening to Death Grips mid-mosh-pit versus alone in my room can produce incomparably different experiences.

Suicide, an early electronic duo composed of singer Alan Vega and instrumentalist Martin Rev, refused to fall victim to this dulling effect. In a reissue of their groundbreaking self-titled debut, the last track of bonus content starts with a 19-minute run of a live performance. In the following four minutes, the concert devolves into utter chaos. Vega, at around minute 21, has to beg the crowd to give his microphone back, to which the crowd responds with energetic boos. Vega closes out the brief interaction with several expletives.

Featuring this track on their reissue is a critically important move for a band whose sound has become a common reference point in a variety of experimental and mainstream genres. The duo’s influence on LCD Soundsystem, who go so far as to namedrop Suicide on “Losing My Edge,” is apparent throughout the album, but especially on the latter’s track “Cheree.”

The drum machine part in this song sounds like it could be a included as an early addition to one of LCD’s intricately layered jams.

Suicide and LCD’s unwillingness to drop instrumental parts until it’s absolutely necessary likewise becomes apparent on this track: Rev, rather than prematurely fade out the xylophone-esque melody post-chorus, instead drops it to a barely audible level and reintroduces it later in a similarly subtle, extended fashion.

This isn’t to knock LCD; they combine influences from numerous other genres, and they reinvent Suicide’s sound by taking many of the band’s ideas to their artistic extremes. But it is to highlight one of the many great groups that clearly drew inspiration from the duo’s music.

But even if this album was entirely irrelevant and never interested anyone, it would still be an enjoyably wild ride of an album. The tracklist opens with “Ghost Rider,” a song whose driving synth-bass melody make for an appropriate homage to the testosterone-fueled fantasies of riding a motorcycle. “Rocket USA,” another gripping cut, follows, featuring an organ melody that maybe at one point was charming but has since been warped by weird chord progressions and Vega’s nervous outbursts.

“Girl,” a possibly sexy song plagued by harsh realism, offers a more self-aware counterpart to “Cheree,” the album’s only ‘love’ song. While the latter tries to convince itself of love, “Girl” is honest, appealing only to lust. Vega here sounds like a meek version of Robert Plant, employing timid versions of the moans for which the latter is so famous.

The original album then closes with the uniquely unsettling “Frankie Teardrop.” This track begins with a standard description of a working class individual (“Twenty year old Frankie/He’s married, he’s got a kid/And he’s working in a factory”) and rapidly transitions into the story of an insane, homicidal man so tortured by guilt that he commits suicide. Yet throughout the song, Vega insists, “Let’s hear it for Frankie.” Why? “We’re all Frankies/We’re all lying in hell,” the singer declares. Pessimistic as it may be, for young people living and working in the hellish uncertainty and nihilism of the late 1970s, these lyrics may have presented a welcome catharsis.

This hints at yet another strength of this album. With election day just past, we are again plunged into a period of uncertainty, as it’s unclear, regardless of the results of the midterms, just what actual difference these changes in appointment will produce. Suicide’s music offers a much-needed solace to those seeking validation and an understanding, observant perspective. And even if you think this assessment is too dour, there may still be something for the band to offer: the group’s similarly excellent second album takes on a disco-oriented vibe, preserving much of its predecessor’s weirdness while adding a new element of lightheartedness.