“Before my wife turned vegetarian, I’d always thought of her as completely unremarkable in every way.”

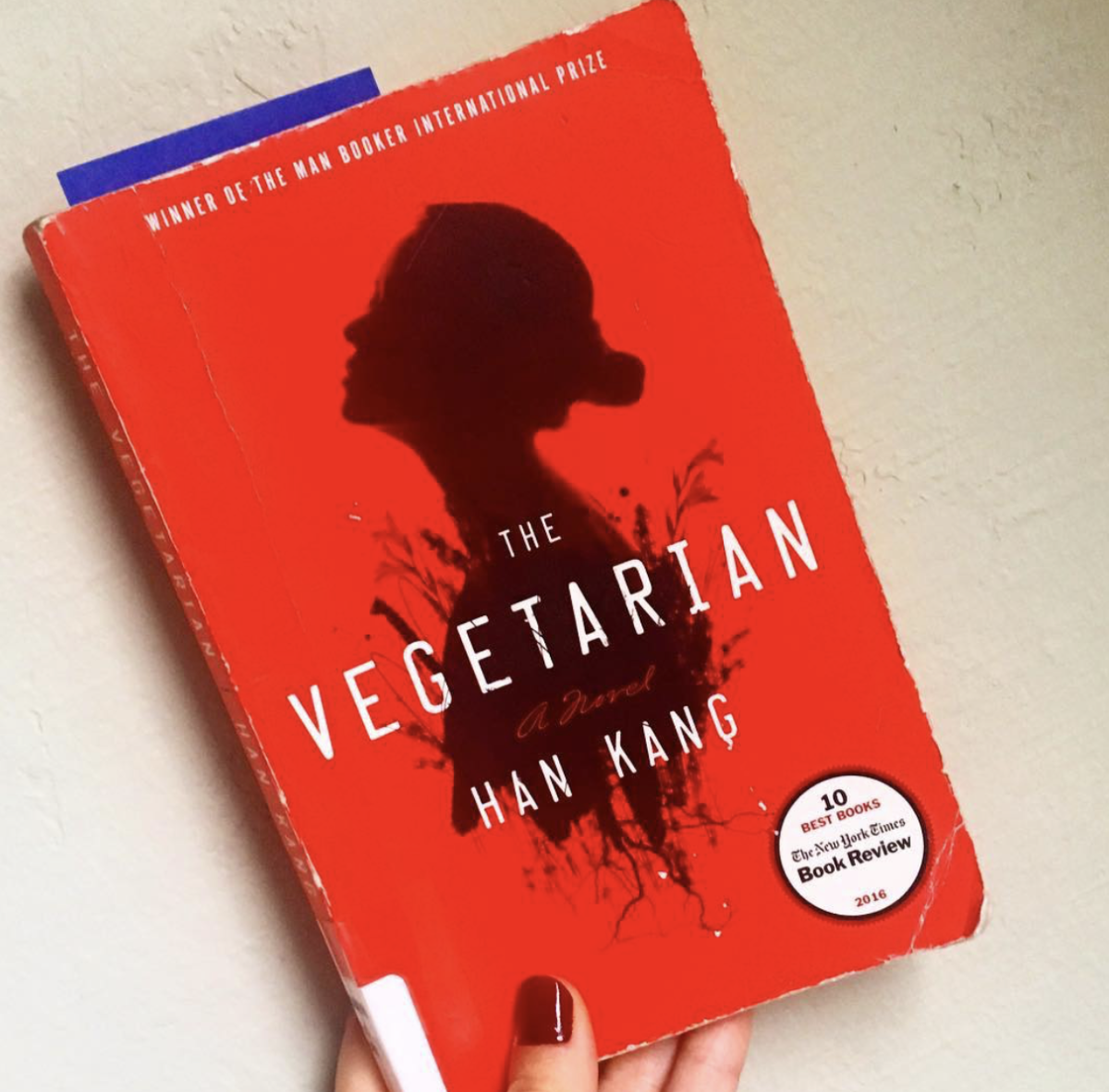

With this benign line begins “The Vegetarian,” Han King’s 2007 debut novel and now winner of the 2024 Nobel Prize, making King the first South Korean winner. “The Vegetarian” also previously won the Man Booker International Prize after Deborah Smith translated it into English in 2016. The book’s anodyne title and bright crimson cover with the black silhouette of a woman sprouting flowers from her chest caught my attention on the bookshelf, conflicting messages that pointed to something deeper and darker beneath the surface.

What begins as a seemingly innocuous choice — to become vegetarian because of a dream — spirals into a fundamental breakdown of South Korean homemaker Yeong-hye’s personhood and an attempt to return to the roots of her humanity. In her dream, she sees her face reflected in a pool of blood, and she cannot bear what she sees. King’s experiences as a South Korean woman and her humanistic insight allow her to display the suffering and fragility delicately contained in modern life through a heart-wrenching narrative.

The novel passes through three sections, as one would pass through different phases of life, told in the third person. Each section follows a different character and demonstrates how Yeong-hye’s choice sends ripples through their lives. First, her husband’s baffled irritation and inability to get through to her leads her father to force-feed her meat, and Yeong-hye harms herself in protest. Then, her brother-in-law, an artist who becomes obsessed with her defiance, convinces her to let him paint flowers all over her body and have sex with her on camera. Finally, we see over the shoulder of her sister who discovers them in bed. Yeong-hye is committed to a psychiatric facility and begins to waste away, refusing to eat at all and passing her bloody dreams onto her sister. She professes she will become like a tree and not have to eat anymore as her sister struggles to make the right decisions for her. The short length and striking violence make this novel a gut punch of passive resistance to inbuilt violence.

King’s prose is so lucid and direct, and Yeong-hye’s demeanor so subdued, yet the subject matter haunts both with a violent and animalistic tone only breaking through the surface in the most tense of moments. King takes Yeong-hye’s vegetarian conversion and uses it to illuminate the violence that permeates human desire, love and passion.

After the bloody dream causes Yeong-hye to swear off meat, she says, “I thought all I had to do was stop eating meat and then the faces wouldn’t come back… now I know. The face is inside my stomach. It rose up from inside my stomach.” She attempts to eliminate all that is not innocent from her life to purge the violence within her. Compared with her brother-in-law’s desire to possess the innocence he perceives in her — which destroys its object in being fulfilled — Yeong-hye strives to swear off desire all together. This is not some form of enlightenment — Yeong-hye suffers immensely, starving to death by the end of the novel. Rather, King holds up a mirror to the reader, as Yeong-hye’s dream holds up a mirror to herself, to prompt us to ask questions about the violence inherent in our lives, what pure innocence looks like and whether we would even permit such a thing. The novel ends hauntingly with Yeong-hye’s question for her sister, as her sister clings to life and normalcy through her obligation to her son, “Why, is it so bad to die?”

Through this question and the culmination of Yeong-hye’s story, King forces the reader to consider vegetarianism in another light, showing how choosing nonviolence can be transgressive and what that can tell us about what it means to be human. Is violence necessary to satisfy our desire to stay alive and, if so, is it worth it? Reading King’s work was a profound joy, and I felt pushed to the limit of my emotional tolerance. It was very much like an emetic, a bitter irritant that stirred up something rooted deep inside me. It may not be the book for everyone. In a very Kafkaesque way, it made me uncomfortably sympathetic and morbidly curious. It forced me to confront myself and the everyday violence I tacitly participate in. I cannot recommend it enough.