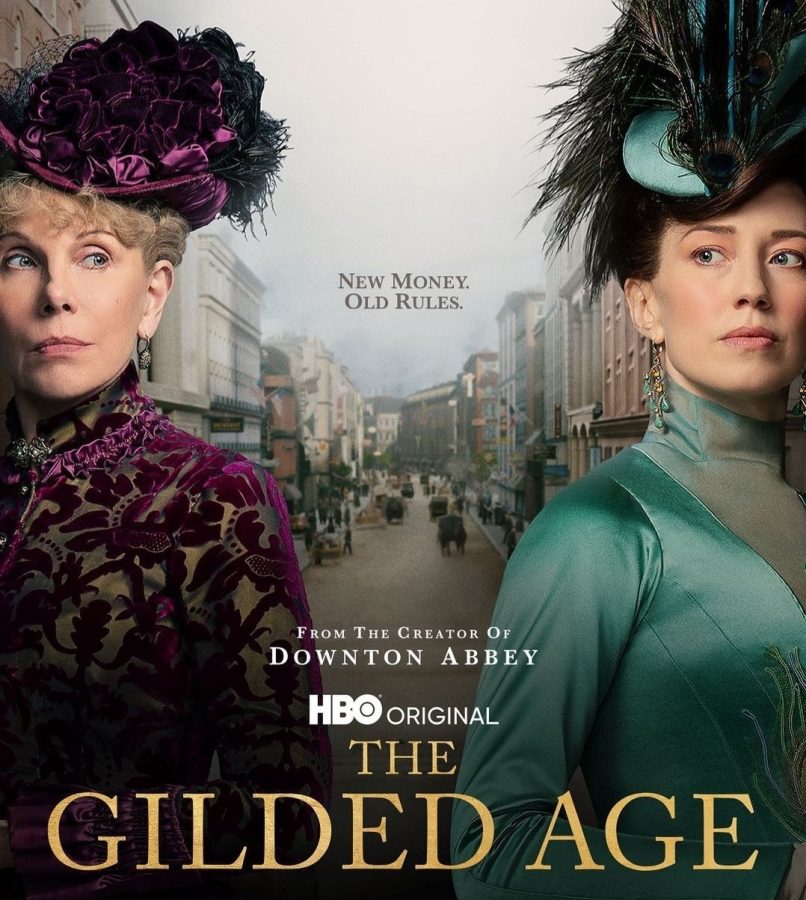

“The Gilded Age” is an Underwhelming Attempt at a Period Piece

Stunning costumes, elaborate sets and gilt-covered mansions promise a look into the rich lives of the 19th century’s New York elite. Unfortunately, very little substance lies beyond the flash of pretty skirts and corsets. “The Gilded Age,” produced by Julian Fellowes as a lackluster follow up to the success of “Downton Abbey,” fails to tell what might have been a captivating story about social upheaval, cultural evolution and the friction that made 1882 New York City such a dynamic landscape.

The first four episodes of the show introduce a variety of characters, many of whom are allied with or against the rising class of “new people.” The Van Rhijns embody the “old people,” who have held high status within American society since its inception. Moving in across the street — in an oh-so-highbrow visual metaphor — are the Russels, who have just entered society after gaining obscene wealth through railroad construction. While both of these families are fictional, they represent very real people.

What shatters the illusion, however, is the money. This series focuses almost exclusively on the wealthy, as the Russels flaunt theirs and the Van Rhijns downplay their own. Wealth is fun. It sparkles, and it looks good on the screen. Yet, one of the glaring oversights that this show makes is ignoring the complicated question of where this money originates.

Fellowes’ previous show, “Downton Abbey,” explores the class differences between those upstairs and those down. It’s the show’s whole gimmick, and it’s a wildly fascinating one. The show focuses on a modernizing world, where the noble family, the Crawleys, gradually lose their influence, prompting regular citizens to debate how involved they want this ruling class to be in their lives. More conservative characters, like Anna Bates, a servant, believe that the great family acts like the community’s keystone. Other characters like Tom Branson, the chauffeur-turned-son-in-law, are very critical of the English aristocracy. Most characters fall somewhere in the middle, but the question of the nobility’s necessity is presented at the very beginning and continues throughout. Conversely, the question driving “The Gilded Age” is whether or not the robber baron’s wife can attend luncheon.

The Gilded Age was a period in time alive with cultural rifts and horribly messy morality. In short, it’s the stuff of good television. According to PBS, while the New York elite spent their leisure hours at the opera, dining out at lavish restaurants and bedecking their dogs in $15,000 collars, 11 of 12 million families lived far below the poverty line. On average, they earned less than $1,200 a year. The aforementioned dog collar costs more than 12 times that. This obviously caused a lot of unrest, especially within the city. The conflict caused violent riots, fueled political machines and sparked social movements that persisted throughout the end of the 19th century. While it might not have been a terrific era to live in, it is certainly fascinating.

The show has so far ignored all of that. Its social awareness is limited to who can attend the opera, whether Bertha Russel can let her daughter out into society and whether or not a member of the Van Rhijn family can marry a lawyer. In its naivete, the show lacks drama. It’s pretty, but it’s boring. And it’s depicting one of the most fascinating eras of American history.

Yet, one character is fascinating. Peggy Scott, a Black woman trying to exercise her literary talents, is fighting to get her short stories published in a New York paper. She’s smart, she’s funny and she’s not as sickly sweet as some of the other characters. Moreover, she faces conflict. While her mother supports her, her father decries the whole endeavor as a fruitless dream. Scott’s relationship with her family also opens an avenue for the show to explore the society of Black elites in New York City. A traditionally underrepresented group, this show has the potential to really explore their perspective and restructure the narratives that still smother Black history.

Scott’s family demonstrates what this show could be. It has the potential to explore this wildly fascinating and turbulent period, which is so vital for the creation of the America that we all know today. The Russel family made their millions from building railroads, but the show never acknowledges the laborers that suffered back-breaking work to produce that wealth.

“Downton Abbey” excelled because it challenged its characters, it created conflict and it explored the various perspectives of different members of the same community. This show exhibits the pretty buildings as if they popped out of the ground without cost. In an age when wealth disparity in America is increasing — when the uber-rich travel to space, and their workers die because they can’t afford their prescriptions — it’s a bit tone-deaf.

I still hope that this show will grow into its potential, but I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone. If you want a period piece that explores societal change, discusses the Industrial Revolution and has interesting characters, watch the BBC’s “North & South.” If you want pretty dresses and not much else, watch this.

Kari White is a senior from the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it state of Delaware. She is majoring in English with a concentration in creative writing, as well...