A male-dominated history is a constant tale of overlooked voices. Just because countless female contributions to the arts, sciences and beyond are ignored does not mean they are not felt in the pulses of change. One such area in which women have played unrecognized roles in developing innovations is the musical genre of jazz.

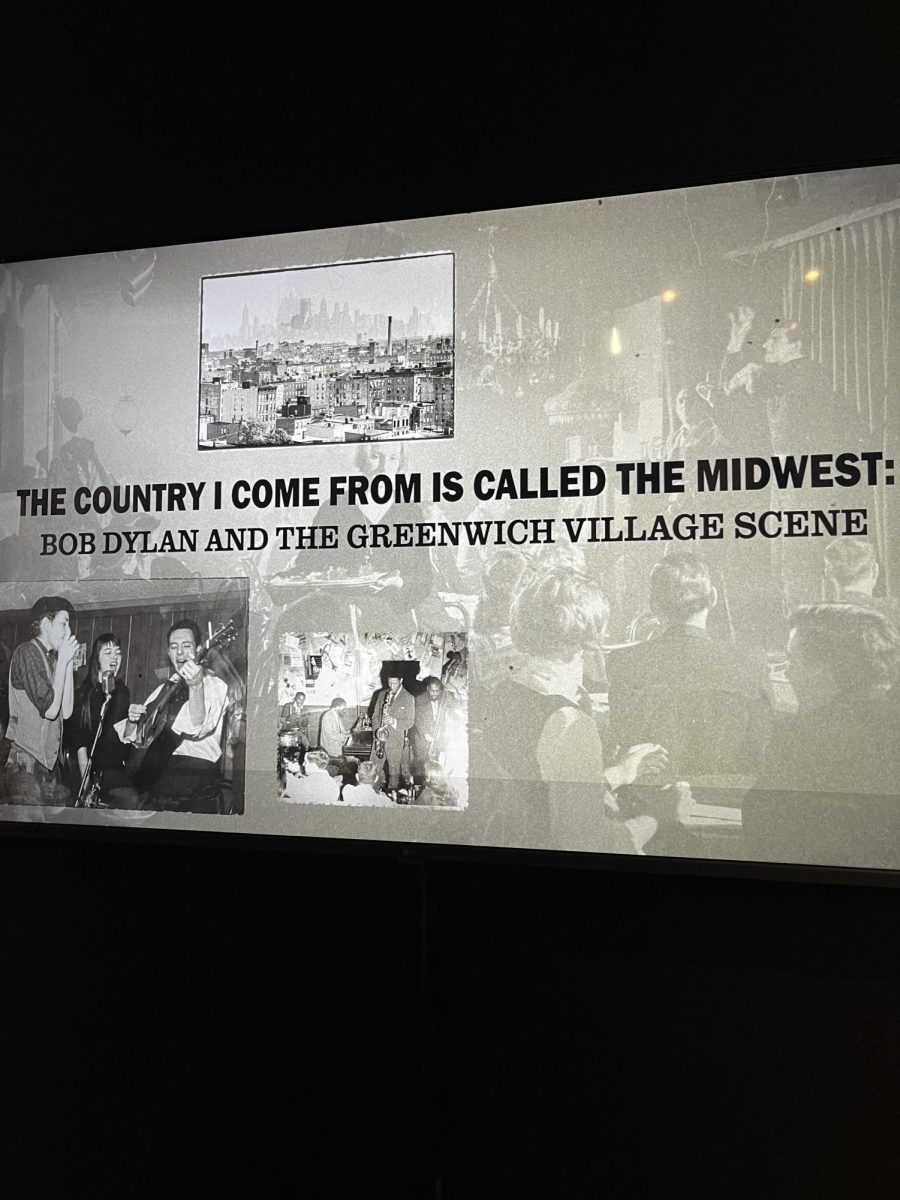

The “Rhythm is My Business: Women Who Shaped Jazz” exhibit at the New York Public Library of the Performing Arts in the Lincoln Center Plaza challenges the narrowed history of jazz as a male-centered genre. The exhibit is so engrossed in all things “jazz women” that even the title is an allusion to the 1962 studio album of American jazz singer legend, Ella Fitzgerald. The exhibit runs until June 13, giving people, particularly Fordham students at Lincoln Center, plenty of time to learn about the many “achievements of female jazz musicians as instrumentalists, bandleaders, composers and arrangers,” according to the exhibit’s audio guide.

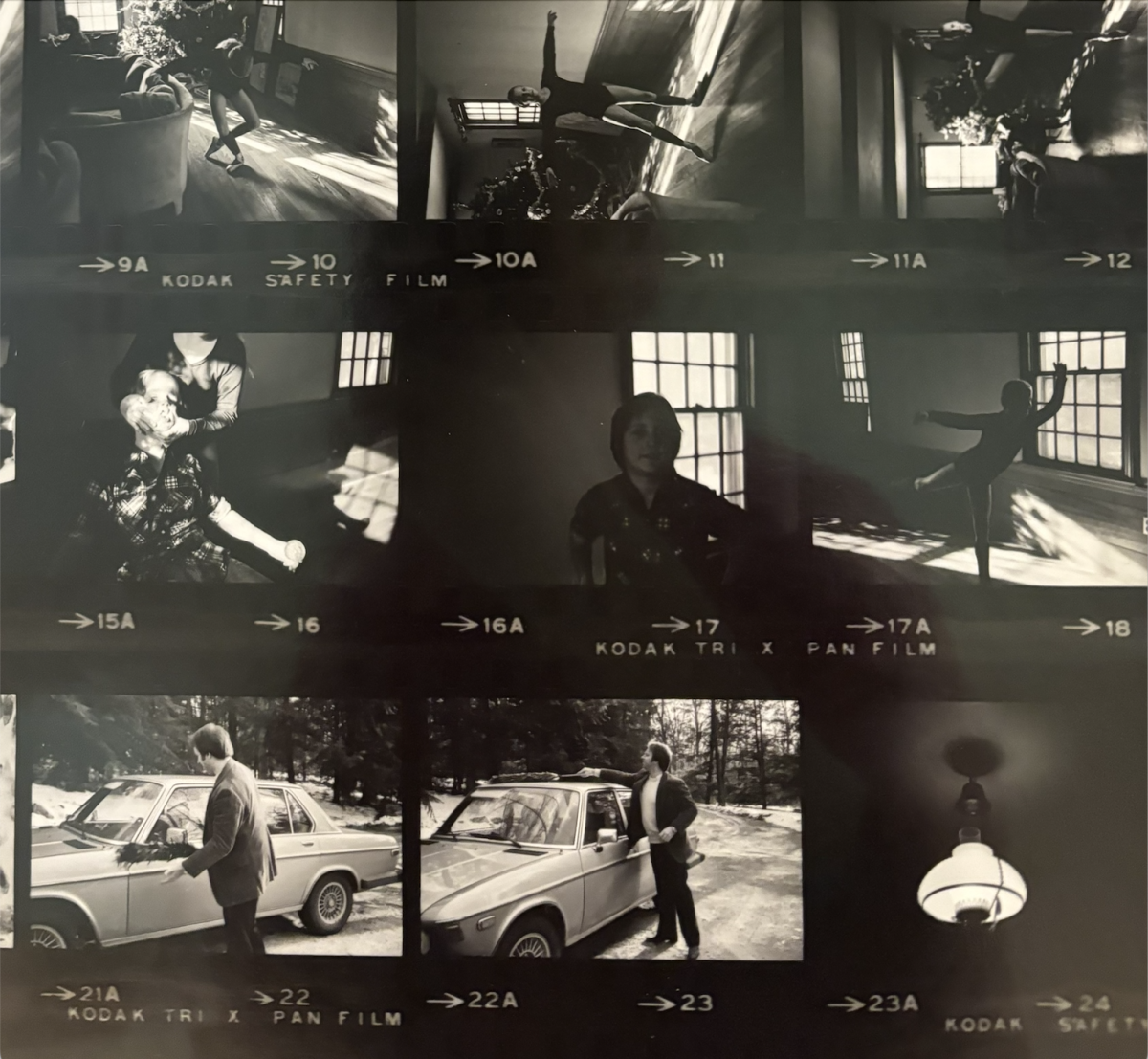

While I fell victim to viewing jazz as a male-dominated industry, my visit to this showcase opened my eyes. The exhibit is small with a number of pictures and plaques scattered around the library walls in addition to two monitors with headphones where you can listen to some jazz. What the display lacks in size is made up for in its riveting historical facts that erase the shadows surrounding these very talented women.

A key factor of the exhibit is the concentration on jazz women’s pioneering accomplishments as well as a pivot in focus from female jazz singers to musicians. This is because the curators of the exhibit found that the female jazz musicians held more unrecognized work compared to female jazz singers, although there is a nod to the fact that the female jazz singers were often dismissed as just entertainers.

While the museum plaques held very enticing information, the audio guide gave an even more enriching experience about the waves women started in jazz. The curator of the exhibit, Kevin Parks, and members from the Music and Recorded Sound Division, Danielle Cordovez and Rebecca Littman, are the voices that take us through lesser-known steps women took in the jazz industry.

Cordovez shines a light on the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, who are known as the most talented jazz players of the 1940s era. The jazz band from Mississippi included white, Black, Latina, Asian and Native American women — making it the first integrated jazz band with all women.

Parks talked about how vibraphone player Margie Hyams joined the Woody Herman’s all-male group. In Linda Dahl’s book titled “Stormy Weather,” Hyams said, “In a sense, you weren’t really looked upon as a musician, especially in the clubs. There was more interest in what you were going to wear or how your hair was fixed. They just wanted you to look attractive, ultra feminine, largely because you were doing something that wasn’t really considered feminine.” Hyams fought against the sexist expectations of women in music by forgoing a cocktail dress to wear the same uniform as the men while on stage.

Littman attributes the fact that Ruth Lowe, a composer, musician and arranger, “wrote Frank Sinatra’s first number-one hit, ‘I’ll Never Smile Again.’” She also mentions Viola Smith, a female drummer who played with “two tom-toms at head height,” a technique and setup no man ever dared to imitate. This astounding woman continued to play until she died at the age of 107 in 2020. Littman cited a quote from Smith that perfectly sums up the message of this exhibit: “Give girl musicians a break! Idea: Some girls can outshine male stars.”

After turning my focus to the written plaques on the walls, I found out that the tales of female jazz players range not just from prominent jazz places like New York City and New Orleans, but also from the western hemisphere to the eastern hemisphere. Toshiko Akiyoshi is a Japanese jazz musician who composed and arranged jazz ensembles. Alice Coltrane, although she is an American, produced jazz music that incorporated Indian instruments such as the tambura and harmonium. Hazel Scott was a Trinidadian jazz pianist and singer. Fun fact: she had such a natural born talent for jazz and classical music that Juilliard accepted her into the school when she was only eight years old.

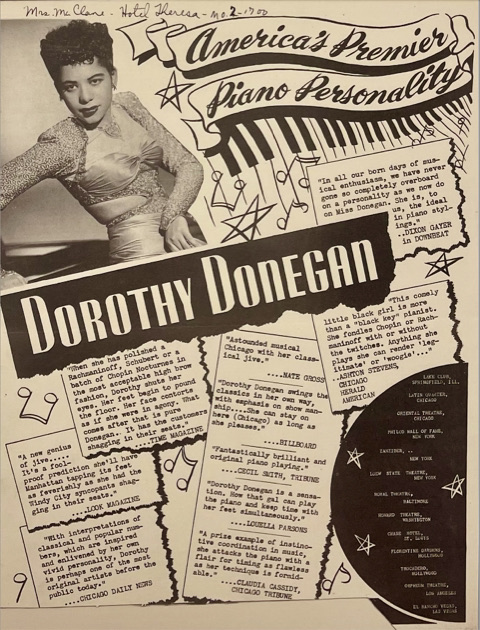

Jazz was an avenue for these leading women to join other industries as well. Akiyoshi has obtained 14 Grammy nominations. Scott’s abilities in jazz singing as well as movie and theater acting led her to be the first African American to have a television show and gain respectable roles in Hollywood. The jazz music mentor and advocate for women in jazz, Marian McPartland, headlined the first Women’s Jazz Festival. Dorothy Donegan, jazz pianist, was the first Black performer at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall. Amina Myers was a pianist, vocalist, organist and composer, and these talents landed her a spot in the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame. Jane Ira Bloom, through her inclusion of electronics to modern jazz, is the “first musician to be commissioned by the NASA Arts Program to create music inspired by space exploration,” according to her plaque at the exhibit.

Despite being faced with boundaries, female jazz musicians continue to strum the chords of change within the genre. Stereotypical gender roles held women back from public and professional spaces, including the stage. Being expected to look and act “feminine” with meekness and passivity was particularly detrimental for women wishing to play jazz due to its freedom of improvisation and upbeat spontaneity. However, the exhibit “Rhythm is My Business: Women Who Shaped Jazz” showcases how women pushed beyond these boundaries. Helping craft a sound of such an important era of music is a testament to the accomplishments in these ladies’ careers.