Weezer’s “Black Album” May Be The Riskiest Yet

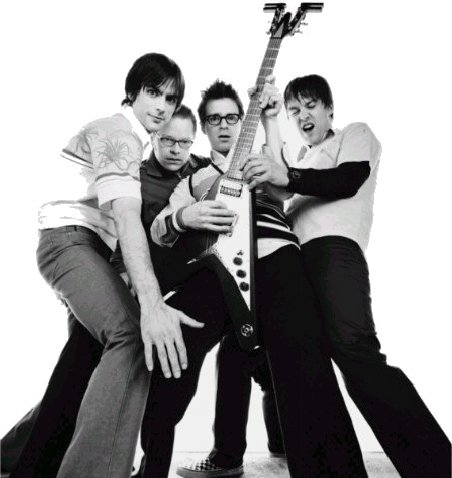

Weezer recently released the “Black Album” which experiments with genre. (Flickr)

By Tommy Tedesco

Weezer, the rock group whose droning guitar riffs and unique lyrical style carved out a distinctive niche in the ‘90s alternative scene, is back with another album. Continuing in the tradition of self-titled studio releases distinguished by case color, Weezer released “Weezer (Black Album)” Friday, March 1.

Those familiar with Weezer’s critically-acclaimed “Blue Album” or cult classic “Pinkerton” may be disappointed that “Black Album” embarks on a new musical path. However, most fans expected as much; frontman Rivers Cuomo has been throwing curveballs since the “Green Album,” so longtime fans are no strangers to taking the good with the bad.

The question of whether Weezer’s new album is worth a listen must be dealt with in two separate categories. If you have never listened to Weezer before in your life, or if you love their recent material, you should absolutely listen to this album. As a fan of early ’90s Weezer, however, I will be writing this review from the perspective of someone who did not really like most of what post-”Green” Weezer had to offer.

The album opens with a jivey guitar riff over a shuffling beat on “Can’t Knock the Hustle.” The mix of Latin melodies in the trumpet, guitar, funk bass and rock beat create a texture that almost transcends genres, which is something seen on Weezer’s recent “Teal Album.”

The new Weezer sound established from the onset of this album mixes alternative rock with seemingly anything that works, from pop electronica to progressive jazz to Latin folk. While the usual lyrical issues persist and believe me, I did not enjoy hearing a 48-year-old Rivers Cuomo say “don’t step to me, b—h” —“Can’t Knock the Hustle” represents the “Black Album” at its best: experimental and fun.

The next track, “Zombie Bastards,” is much less interesting. Rather than continue the risk-taking that made the first track odd yet entertaining, Weezer opts for a very safe, modern pop sound. I have never been a fan of crowd noises (“ayys” and “oohs”) injected into choruses, and Cuomo does not change my mind here. Like most of late Weezer, it contains a catchy melody, but there is a great distance between catchy and good.

Weezer slows it down a bit on “High as a Kite,” falling back on some old sounds, much to my appreciation. This track is no instant classic, but I could see it as a weak entry on “White Album,” and that is certainly something. If you are a fan of the old Weezer sound — those droning guitars filling in all the empty space while Cuomo belts out a melody — then you will find something to enjoy in this track.

“Piece of Cake” has all the “doo-doos” and choral repetition you would expect from some garbage instant-hit on 92.3 FM. I like how Cuomo chose to fill in the bridge and chorus with sustained synth chords, but I do not like how I have to hear one of Weezer’s worst lines in history over it, repeated ad nauseum: “she cut me like a piece of cake,” over and over in that nasally, boyish delivery that can only be Rivers Cuomo. Man, sometimes it is okay to hire a ghostwriter.

“I’m Just Being Honest” sounds like a late 2000s emo-pop hit. I really like it. It captures the same feeling the All-American Rejects do on “When The World Comes Down.” It is fun, singable and a little nostalgic.

In “The Prince Who Wanted Everything,” Cuomo tells a story. Sustained synth chords (a staple of this album) supplement a simple, repetitive guitar riff, but all the focus is on Cuomo’s voice. There is nothing too fancy in the drums, just a boom-chick with a strong backbeat calling back to Tears for Fears. The simple execution and lyrical style introduces a mix of pop-rock and folk storytelling, and it comes together quite nicely on this track.

A song I cannot figure out is “California Snow.” On one hand, the transition from the upbeat “Byzantine” to the dark mood, droning synth and echoey vocals of “California Snow” work as a sort of callback to “Pinkerton,” Weezer’s darkest album. On the other hand, Weezer throws in some staples of modern pop, which work as well as they always do in Weezer songs: not at all. The rap sections, for instance, performed by Cuomo, simply cannot be unheard (believe me, I have tried). The last 20 instrumental seconds of the track purely is where it really shines, and it completes the album on a dark, pondering note.

It is fun to jeer at new, strange sounds, but much more can be learned by picking out what works and what does not. As a fan of old Weezer, it took me a few listens to tune my ear to the new sound, but I think there is something enjoyable here. There is a lot that does not work at all, too, and I would never claim that Weezer should be applauded simply for the act of risk-taking in and of itself.

Still, Weezer’s search for a new sound is admirable, and they stumble across some memorable moments along the way. If nothing else, this album effectively communicates its central message: Weezer is going to keep making whatever music they want, and if old fans take issue, they are having too much fun to care.