A Look Back at Fordham’s Experimental Bensalem College

Graduating from a college, of any kind, is viewed as an achievement. It means a student has fulfilled the given requirements for a degree. Typically, these requirements are relatively standardized. Students earn certain grades in classes based on what they are pursuing a degree in and completing a set number of credit hours. However, there are exceptions to this structure.

What if there was a college with no exams, no papers, no compulsory classes? One where students didn’t even need a high school diploma to get in? According to Isabella Taves, quoted in “A Radical Departure: College in the ‘60s,” this was the case at Bensalem College, Fordham University’s own short-lived experimental college.

The goal of this college was “to find out, students and faculty alike, what education is, what we need in this day and age, how to learn, how to teach, and what,” according to Elizabeth Swell, Ph.D., an original chairman of the institution. Despite the lofty ambitions of the school, little planning was done ahead of time. James McCabe, Ph.D., explained in A Radical Departure: College in the ‘60s that the idea was for the students to essentially run the school with the faculty through democracy. Students held the power to fire and hire faculty in addition to taking part in the admissions process.

For the first year, students were admitted to Bensalem through the same process as they would be for Fordham College, according to John Coyne in “Bensalem: When the Dream Died.” After this initial acceptance, a separate admissions process was created where acceptance was based solely on an interview with two students and a faculty member. Once admitted, students would spend three full calendar years at the school. The first six to nine months were meant to be spent studying broad topics before choosing a specialization. The only requirement was the study of Urdu, though even this didn’t last long, as students revolted against it, according to Taves.

Graduation from the college was guaranteed to anyone who completed the full three years. Along the way, students could choose to take any classes or none, as there were no grades. Students were simply obligated to keep a portfolio of their experiences throughout their time at Bensalem, according to Coyne. The college was less about academics and more focused on life and finding one’s individual passion.

Before the school opened, the New York Times published an article, “Fordham to Test Utopian College,” which quotes Swell as stating, “We hope to make life so interesting that students won’t need LSD.”

During Bensalem College’s first semester, it was a wonderful place to be, wrote Coyne. The students were highly intelligent individuals with interests in Latin, philosophy, religion and more. They took advantage of the freedom to inquire in their own way and made the most of what Bensalem had to offer. Coyne’s article, published in Change Magazine, listed some achievements of these students. When the first class of a mere 17 students graduated, six of them won Woodrow Wilson fellowships. Additionally, three won Danforth fellowships, and the majority went on to continue at prestigious graduate programs, according to Coyne.

However, this type of outcome from Bensalem did not last long. Coyne wrote that the college earned a reputation as the “free and experimental school, a place where you could do your own thing.” This caused it to get the attention of students seeking a college to take over rather than the intellectuals of the year before, explained Coyne.

The conditions at the college began to deteriorate, as it was hard to get the required 75 percent majority on any decision, according to Taves. Bensalem College moved off Fordham’s Rose Hill campus for its second year, and the college then consisted of one building where not only were the classes taught, but both students and faculty lived, according to Taves.

According to Coyne, who visited the building in May of 1971, the college could have been classified as a “slum.” He wrote about several encounters he had with people during his visit, none pleasant. Both students and faculty expressed a desire to get out as quickly as they could, saying the place made people crazy, according to Coyne. A professor additionally complained about the lack of privacy at the school, saying that staff would try to hide away from the students. “My wife and I will be making love and some nut walks in, bumming for a cigarette. Weird, I tell you,” he told Coyne.

A student who Coyne spoke to had recently graduated and explained that the school was not beneficial for him. When asked what he studied, he replied that no one at Bensalem was studying anything and called the school a joke. The student said that he was leaving as soon as he could. However, the student’s wife, who lived with him but didn’t attend Bensalem herself, told Coyne that not everyone was bad and that they had made some friends.

In November of that same year, the New York Times published an article entitled “Fordham Asked to Disband Experimental College.” The brief article stated the campus council had voted to phase the school out. The reason was said to be high rates of student dropouts and faculty turnover. The plan was to not admit any more students and have the last class graduate in June of 1974. At the time of the article, Bensalem was awaiting a decision from the board of trustees to determine the school’s fate. Ultimately, it was agreed upon to close the school, and the experimental college Bensalem became nothing more than a piece of Fordham history.

The idea of an experimental college did not begin or end with Bensalem College. Many shared in similar fates, while others are still around today. “A lot of people made very good use of the freedom, and a lot of others should have gone somewhere else,” stated Swell, who initially proposed the concept of Bensalem. According to Taves, when Swell resigned, she went on to say that she had “no idea how destructive absolute freedom could be.”

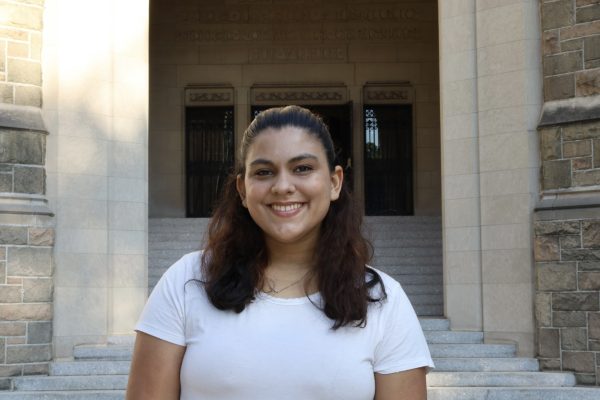

Julianna Morales is a senior from Pittsford, N.Y., majoring in psychology with a double minor in English and disability studies. Julianna joined the Ram...

Jeffery Beam • Aug 18, 2022 at 2:05 pm

Sorry if this is a duplicate comment. I’m thinking it did not go through. The correct spelling of Elizabeth SEWELL’S last name. You might be interested in her “memoir” of the experiment, AN IDEA, published by Mercer University Press. I took a seminar with Elizabeth in 1974 at UNC-Charlotte. I was working toward my Bachelor of Creative Arts in the Art Department when she came as a visiting scholar. We remained friends. My program was inspired by such experiments as this and Black Mountain College and was similar in many ways.

Jeffery Beam • Aug 18, 2022 at 8:25 am

Elizabeth SEWELL not Swell. I took a seminar with her in 1977 at UNCC while receiving a Bachelor of Creative Arts degree in writing. A program not unlike this experiment in some ways. More on Bensalem, see her “memoir” about it: An Idea, Mercer University Press, 1983.