ASILI Hosts Lecture on Intersection of Blackness and U.S. Criminal Justice System

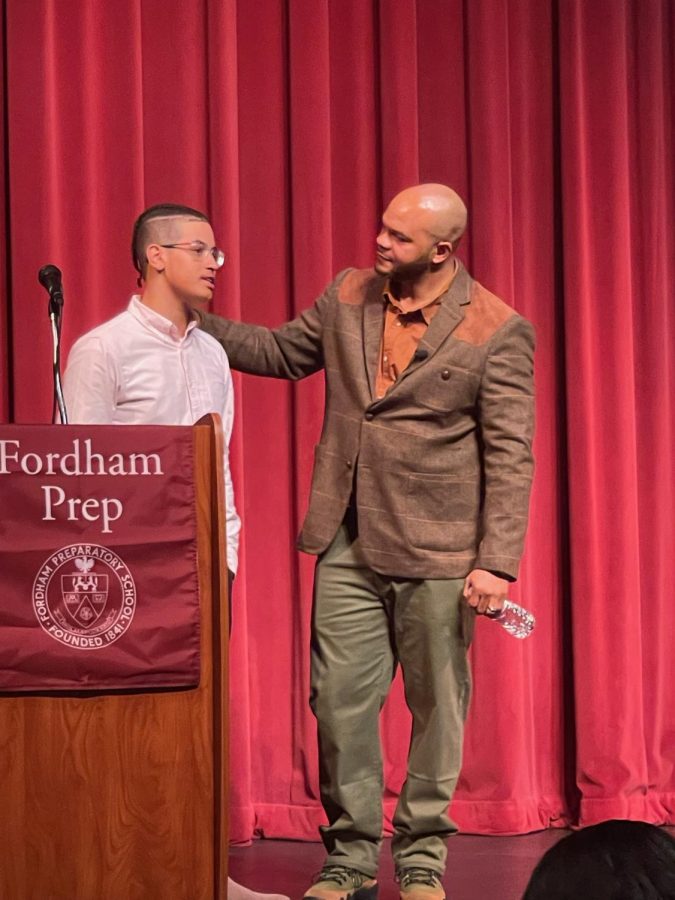

This past Wednesday, Fordham’s Black Student Alliance (ASILI) held their annual Black History Month keynote speaker event. The keynote speaker, Kevin Richardson, is a survivor of the Exonerated Five, formerly known as the Central Park Five. Today, Richardson is an advocate for criminal justice reform and regularly gives speeches telling his story with the prison industrial complex and his life during and after his wrongful conviction as a teenager.

Richardson was 14 years old on April 19, 1989 when he and four other teengers were reprimanded leaving Central Park and subsequently accused of the violent rape and assault of a white female jogger. All five of the boys were convicted on charges including attempted murder, rape and assault, each spending between six and 13 years in prison. Richardson was on his way home when a cop told him to “freeze,” and, although he had no real reason to, he ran. As Richardson tells it, he was apprehended by the police, but he “wasn’t scared of being arrested, [he] was scared of breaking curfew.”

The environment Richardson grew up in imbued him and many other young Black men with an inherent distrust of the police, so he ran back into the park, got covered in mud and knocked out by a police helmet. At that moment, he said he thought his life was over. Richardson does emphasize, however, that “things did happen in the park that day, a woman did get assaulted and lose 80% of her blood — there were six victims that night.”

Richardson, until that point, said he had been a timid kid growing up in Harlem near 110 and St. John the Divine. He said he had dreams of playing the trumpet and college basketball at Syracuse University. In the months leading up to their conviction, the boys were blasted in a media frenzy which painted them as monsters, using terms like “savages” and “wolfpack” to describe them. Richardson detailed the racist attacks his family endured and the calls his mother received daily telling her “your son deserves to be castrated” among other horrific threats. Richardson ended up spending seven years in a juvenile detention center.

He said he chalks up his survival in the prison system as a young Black teenager who was accused of a crime he did not commit to three essential elements: resilience, perseverance and strength. Without which, he said, he would not have been able to make it through.

When asked how he kept his optimism, Richardson explained that he “just did,” and that he believes it was God walking him through the experience. He expressed a deep reverence for the people who supported him and all members of the Central Park Five, particularly his mother, whose “grace and presence kept [him] who [he] is.”

The day Richardson was released on June 24, 1997, he recounted his feelings of fear — a fear that his own community, that society, would continue to reject him. He explained his experience with the parole board and the humiliation of registering as a sex offender and paying weekly fees to stay out of prison.

He was angry, Richardson explained, but not at society. Rather, he was angry at the failure of the media to look at both sides and use logic and angry at the system designed to keep Black people behind bars. Richardson explained that his release was not the end of the nightmare that began in 1989, and that he had to learn to channel that anger he felt towards something meaningful.

Richardson said he began to try to learn how to make sure there’s never another Central Park Five, Scottsboro Boys or Emmett Till — “all the situations where things happened when they shouldn’t.”

“We must unmute the uncomfortable, so people get used to what you’re speaking about,” said Richardson.

When asked what he meant by that, Richardson explained that people need to know about what he, and the people he represents, have been through.

Richardson now works closely with the Innocence Project, which “works to free the innocent, prevent wrongful convictions, and create fair, compassionate, and equitable systems of justice for everyone.” He said his experience taught him the prison industrial complex benefits from getting more people into prison.

“Without arresting people, they wouldn’t have revenue, similar to the slave trade. It is designed for you not to come out,” said Richardson.

He and the other men from the Central Park Five are now advocates for the legal codification to require minors to be recorded from the moment of their apprehension through the entirety of their interrogation. They do not want other young people to experience the same abuses and coercion they did in 1989.

Richardson encourages people wherever he goes that “you do not need to be an activist to be active.” He said he believes that change takes a community, but he encourages everyone to call and email their representatives and contribute in any way they can to create a true justice system; more than a legal system, but something righteous.