For the past year, Professors Aysha Ames and Jeannine Hill Fletcher have worked together to uncover the long-buried ties between Fordham University and slavery in the United States. Both scholars began their research separately, each around a decade ago, but have now worked together for a little over a year. They were inspired by the Georgetown Memory Project, an initiative that seeks to identify descendants of the 272 people enslaved by the Jesuits, who were sold in order to pull Georgetown University out of a financial crisis. The project encouraged them to ask important questions about whether Fordham’s own Jesuits were involved in enslavement. The short answer: yes, they were.

Archbishop John Hughes, the founder of St. John’s College, the predecessor to Fordham University, was himself an “overseer” of people enslaved at Mount St. Mary’s College and Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland. Archbishop Hughes, nicknamed “Dagger John” for his prickly personality, was an anti-abolitionist who was personally involved in America’s economy of enslavement as both an overseer of enslaved people and as a religious leader in an American Catholic Church that reaped economic benefits from slavery. During his term as Archbishop of New York, Hughes preached and promoted the idea that slavery was consistent with Catholic teaching.

The professors uncovered records indicating that many of the Jesuits who arrived in New York to work at Fordham spent time at St. Mary’s College in Kentucky, where they used enslaved labor to run the college. Fordham and St. Mary’s also engaged in sustained financial transactions over many years. For Ames and Hill Fletcher, this relationship ties Fordham to the institution of slavery through the flow of cash and ideology. “Fordham adopts the history of St. Mary’s College, thus, also adopts St. Mary’s ties to enslavement,” the professors wrote in a summary of their research.

Ames, director of legal writing at Fordham Law School, is a descendant of people enslaved by the Jesuits at Georgetown, an identity that has impassioned and personalized the research she has been doing.

“I think because I am a descendant, there is this element of there are people who have been erased and whose stories haven’t been told, and I do think I come at it with that lens of looking for these people who have been erased from the history here and erased from the history of the Jesuits,” said Ames. “That’s generally my motivation, that there are people who helped to build many of these institutions who are unknown, and their histories have been suppressed.”

Their research encompasses various aspects of Fordham’s history, including research into Hughes as the university’s founder, research into the means by which Fordham’s founding was funded and research into who and what is included in the university’s narrative about itself.

“We tell our story at Fordham that we were founded to serve the excluded,” Hill Fletcher said. She explained that this narrative made it difficult for her to confront tough questions about the context of the school’s founding. “For 20 years, I never even asked the question about the timing and the economy and the possible ties [to slavery]. It was as if the initial barrier to asking the question was built into the way the community was creating itself.”

Last spring, Ames and Hill Fletcher sent a letter to Fordham’s Interim Chief Diversity Officer Kamille Dean explaining their research and requesting assistance in establishing a university-wide task force to conduct further research into Fordham’s ties to enslavement in collaboration with the University of Virginia’s Universities Studying Slavery consortium. The consortium includes over 100 academic institutions invested in uncovering their own ties to slavery. The group assists one another and promises mentorship opportunities to researchers beginning similar projects at other universities.

At the beginning of this semester, James Felton III replaced Dean as the new vice president for equity and inclusion. Ames and Hill Fletcher say they are now in communication with Felton and have met with him briefly about the project. When asked about the status of the project, Felton said in an email that discussions are ongoing. “My preference would be to bring the professors and other individuals and groups working on Fordham diversity issues under the umbrella of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Council,” said Felton, “so that we may pool our expertise and support research into the university’s history around race and slavery.”

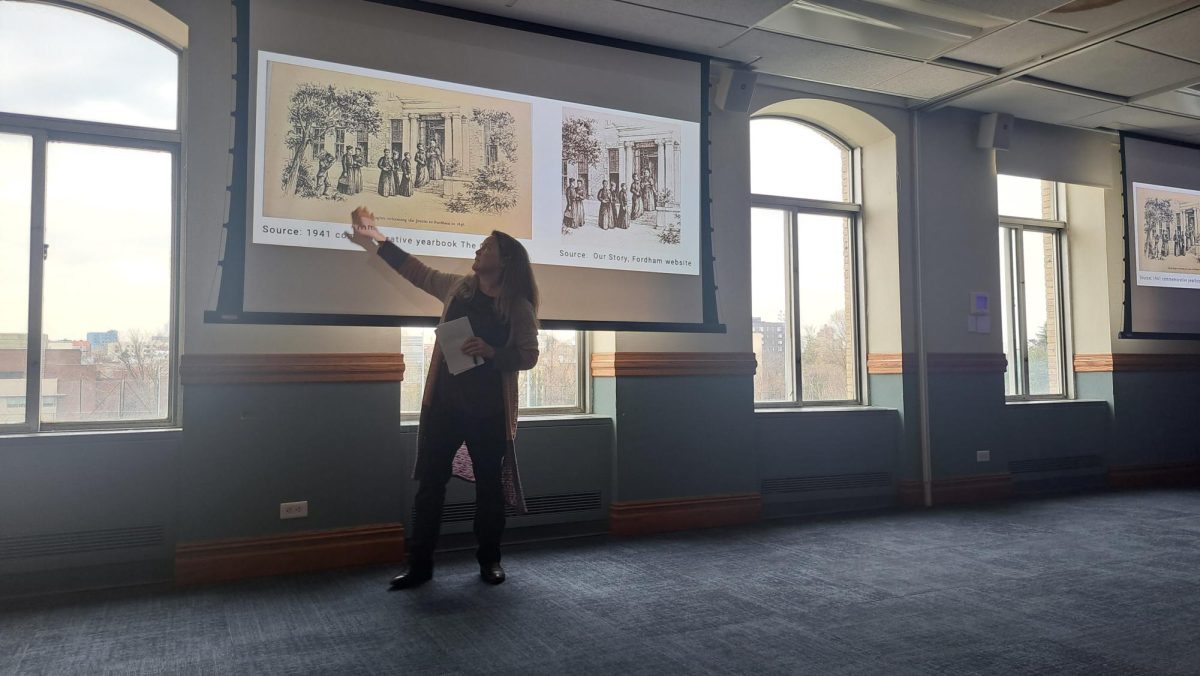

In their letter addressed to Dean and then Felton, Ames and Hill Fletcher write that archival records they reviewed in their research indicate “[s]ome of the wealthiest Catholic slave-holding families in the nation sent their sons to Fordham.” This further complicates Fordham’s narrative of the excluded, the researchers argue, especially as they uncover evidence of Black erasure within the university. The two professors point to a specific example of this they uncovered in their research: a drawing commissioned for The Centurion, Fordham’s 1941 commemorative yearbook, depicts Archbishop Hughes welcoming Jesuits to Fordham in 1846 and features a Black man carrying a box of luggage behind the line of priests. The photo is also featured on a Fordham web page called “Our Story,” however, the Black man in the original art is cropped out of the online image and removed from the narrative.

Research into Black erasure is being conducted nationally in a movement ignited by a 2006 report from Brown University where researchers self-investigated Brown’s ties to enslavement, and the subsequent book, “Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery and the Troubled History of America’s Universities,” written by Fordham alumnus Craig Steven Wilder. Hill Fletcher spoke about the impact the national movement has had on her own research.

“The national scope is universities are starting to ask these very specific questions about their histories, and so thinking historically with a scholarly lens, you’re reading along, and you’re saying ‘Oh, okay, yes, universities,’ and then you kind of realize, ‘wait a minute, what about my university?’” It was from then on that Hill Fletcher began to ask herself more critically about how Fordham was funded, and she began taking trips to the archives in the hopes she might dig up some answers.

Both Hill Fletcher and Ames expressed the difficulties involved with doing the kind of archival research necessary to uncover Fordham’s ties to enslavement. “There are a lot of roadblocks,” said Ames. “Archives require a significant amount of resources to remain accessible, for documents to be maintained and preserved, especially if they were not collected with the idea that they would someday become public. It’s hard to do after the fact. A lot of collections don’t even know what they have.”

For Ames and Hill Fletcher, archival research can be grueling because it is both complicated and time-consuming, but also because it takes a heavy emotional toll. “It can be lonely and isolating work. It can be depressing work,” Ames continued. “You read about the accounts of the Jesuits and how they treated those that they enslaved. It’s not pretty. It’s not pretty at all.”

Hill Fletcher said that working with Ames has made the archival research much more rewarding. She has been working on this research for nearly a decade with support from the former Dorothy Day Center for Service and Justice, which was incorporated with Global Outreach to become the Center for Community Engaged Learning. Hill Fletcher said that Ames reaching out to her was “transformative.”

“A lot of this work was very lonely hours just going through [the archive] and finding something that you know is significant, but you’re not sure who else has any sense of what the import is,” said Hill Fletcher.

Between barriers in archival research and the imaginative barriers borne of a specific university-created narrative about Fordham’s history, Ames and Hill Fletcher know they have a long road ahead of them in this project. “Universities in general, and most times administrations, can be a little hesitant to engage in this work, especially not knowing what the research may uncover,” Ames expressed.

However, the national movement and the research both professors have begun at Fordham give them hope that their visions for the project might be realized. “What I would like to see come out of this [research],” Hill Fletcher began, “is the many, many, many histories and stories… that have been erased and suppressed.”

Uncovering these stories, Ames argues, is important for descendants around the country, but it is also important for future students to understand the university around them. “Students can take a critical and curious look at [Fordham],” Ames said. “As they’re engaging in this institution, they can ask themselves, ‘Is that story the most inclusive story? Who is missing from this narrative?’”

Hill Fletcher expressed hope that students will be interested and involved in the research that she and Ames have begun, saying that it is often student interest and activism that drives this type of anti-racism work. “Student activism around these issues has often been the engine that has driven the explorations at other institutions,” Hill Fletcher said. “[Ames] and I are working on this as scholars… but one never works in an institution alone. I would like for students, as they’re walking around the institution, to really be asking themselves the question, ‘How did these things come to be the way they are, and what is the story we’re telling?’”