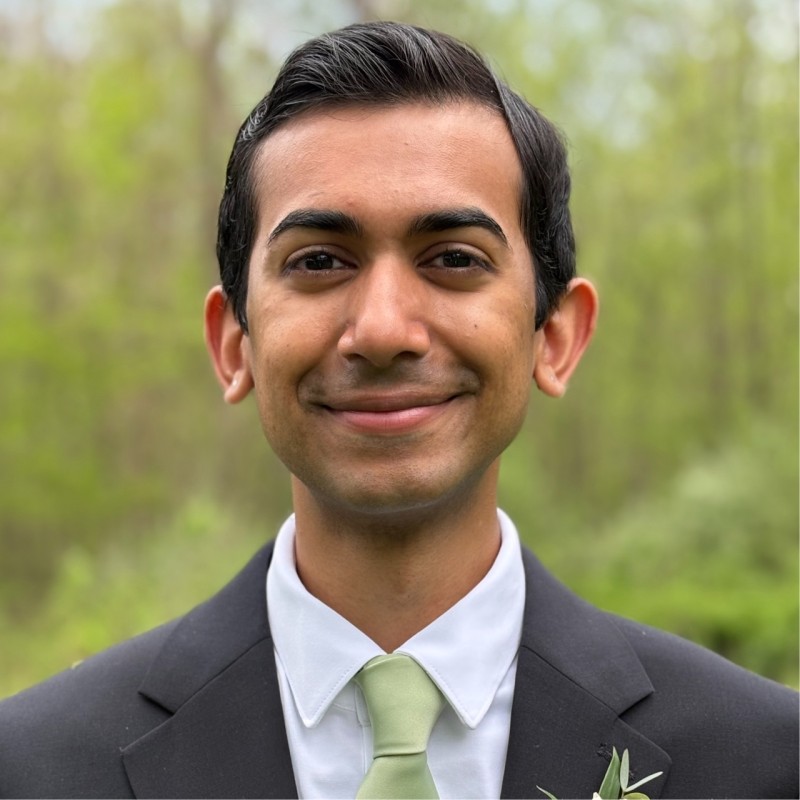

Olivia Lanford, FCRH ’26, is a computer science major and biology minor pursuing the pre-health track who participated in Fordham’s Summer Undergraduate Research Program. Lanford worked with Dr. Kaoutsar Nasrallah as a research assistant focusing on neuroscience and inhibitory receptors in the brain. Nasrallah is new to the university and is just beginning her research.

These receptors are called GABA receptors which are made up of different subunits. Lanford focused on the Delta subunit. In these beginning stages, Lanford compiled preliminary research on how stress can modulate the expression of the Delta-GABA receptor. The research’s focus was on the dentigerous region of the hippocampus, located in the temporal lobe of the brain. She looked mainly at regional differences between the front and back lobes of the brain.

Lanford focused on the delta of the hippocampal region because it is dense in the Delta-GABA subunit. Lanford and Nasrallah wanted to look at the ventral dorsal region spatially as the dorsal region is more implicated in spatial navigation and cognitive function. According to numerous literature reviews, the ventral region is focused on stress, memory and “affect.” This makes it an interesting place to study the Delta-GABA subregion.

Working in a wet lab, there is a focus on behavior and staining protocols. Lanford’s work has surrounded the hypothesis that stress exposure in mice could cause a change in expression of the Delta subunit. Her overall goal was to see if stress has any correlation to the alteration of the Delta subunit. As the Delta subunit is important for different issues like epilepsy, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the overall goal for her research is to target new therapeutics by understanding how the Delta-GABA is modulated. A restraint stress model was conducted to induce stress in mice. Then, they dissected the brains of the mice. This was done to perform an immunohistochemical process that takes antibodies that are specific to whichever protein is observed.

“In our case, we looked at Delta subunit protein and the antibody that binds to that,” said Lanford.

Lanford compared control mice that did not have any stress to stress mice. Under the fluorescent microscope, there is an observable difference in the fluorescent color of their brains. She has completed two cohorts; each cohort is around eight mice — four being no stress in home cages and four that were under stress induced from tubes made for mouse restraint stress. Restraint-stressed mice were in tubes for a period of 90 minutes which is considered acute stress. This core factor of her research was focused on acute stress versus chronic stress because previous literature claims that chronic stress can make the Delta subunit decrease in the dorsal region.

Having done two cohorts and wanting to do more, Lanford has some data expressing differences in ventral regions where control mice had standard levels of Delta-GABA expression. She noticed when stressing the mice out the Delta subunit increased in this expression. There has not been a lot of testing of this theory so there is little written comparing the dorsal and ventral.

Lanford said she did not observe change in the ventral dorsal region either, but this does not reject any theories as she wants to redo the chronic stress aspect of the research. However, it did show that there could be something different regarding how acute stress, a short duration stress can affect the Delta subunit, differs from chronic stress, and the way that your brain changes, called neuroplasticity, when you learn or you go through something, such as a new memory.

Things like PTSD rewire and change different parts of the brain and create new memory engrams that show how stress and duration of stress can change the brain. She is curious to look at the hormone itself in mice and humans. In mice, that hormone is corticosterone. Her interest is in how this hormone can modulate the Delta receptors.

Lanford’s proposal of an idea for the Summer Research Program looked into around 26 sources. “As we started to get more data, and as I needed to put together the experiments, I needed more than 30 sources,” Lanford said. She expressed that she goes down rabbit holes to get information about restraint stress. The summer program began May 28, 2024 and ended Aug. 6, 2024, when final presentations were given. The Summer Research Program helps students pursue what they’d like to learn as an environment to get students started and give them space to conduct research.

Hadar • Sep 12, 2024 at 12:36 pm

Very insightful story and impressive research!