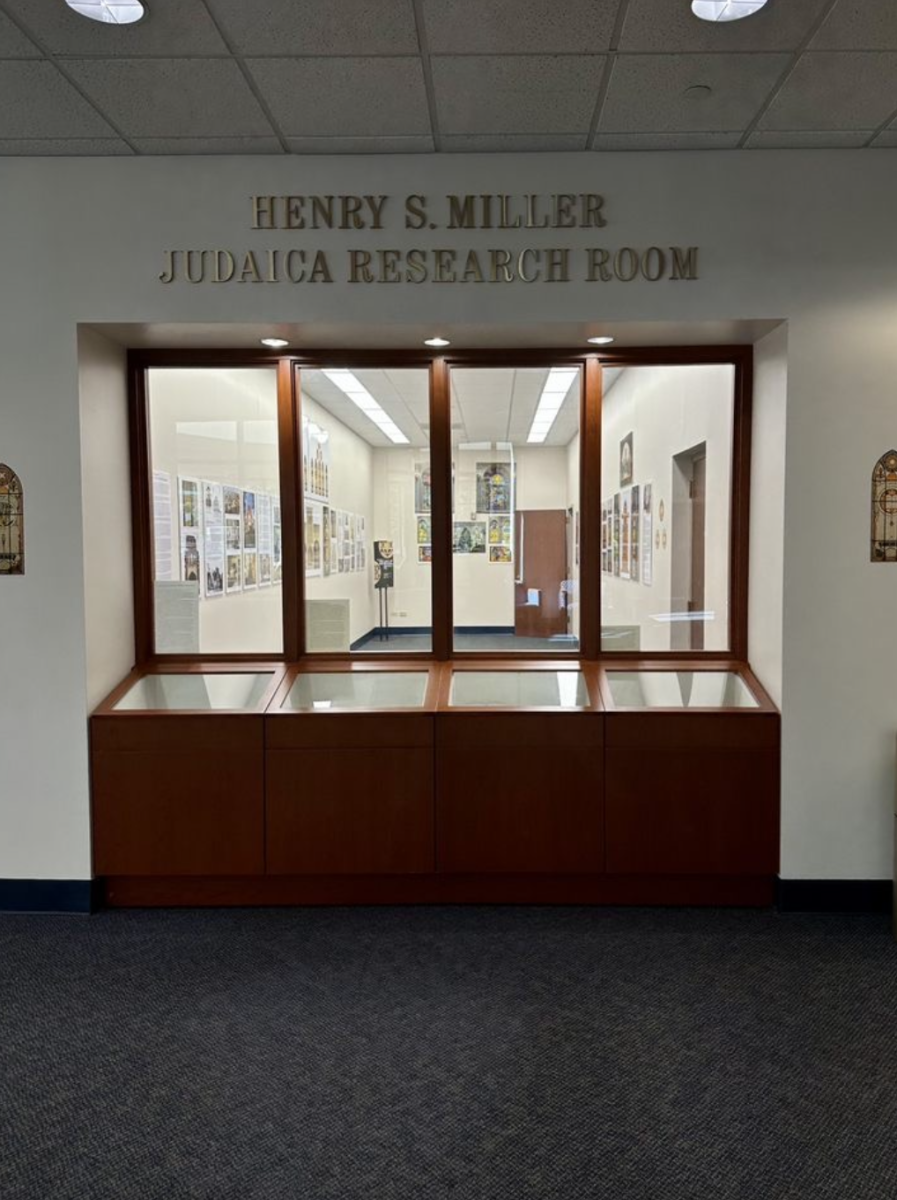

On Sunday, Sept. 10, Walsh Library unveiled its latest exhibit, “The Light of Revival: Stained Glass Design for Restituted Synagogues of Ukraine.” The exhibition displays three stained glass window designs by Eugeny Kotlyar made from 1995-2005. It is located on the fourth floor of Walsh Library within the Henry S. Miller Judaica Room and will be open through Dec. 8.

Eugeny Kotylar is a professor of art history at the Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts in Kharkiv, Ukraine, and came to Fordham through the AAJR-Fordham-NYPL Fellowship for Ukrainian Scholars. He first began working with stained glass in the 1990s amidst a cultural and community movement in Ukraine to restore houses of worship that were desecrated and often destroyed by years of Soviet rule. “Many of the sacred buildings, churches, synagogues were appropriated for swimming pools, for storage facilities, or if they were lucky, for archives for workers clubs… As a result, many of the synagogues were either destroyed or certainly the sacred art has been destroyed,” said Professor Magda Teter, chair of Shvidler Studies at Fordham and administrator of the fellowship program Kotlyar completed. Jewish architecture, including existing stained glass windows, were lost to pogroms such as Kristallnacht, where Nazis burned over 900 synagogues in a single night.

This destruction was followed by a community revival on all levels. As Kotlyar puts it in his opening remarks at the exhibition, “a spiritual life was reviving in the grain, and it became necessary to return the houses of worship to joyful life.” It involved a return to practice and theology, with rabbis even traveling to bring religious education to Ukrainian Jews. Artists, too, especially those working in synagogue restoration, had to experience a reeducation of sorts — as Teter explained: “They all lived in, for generations, in a culture, in a society and in a system that worked to erase religious identities and religious knowledge… They also had to learn what is appropriate, what is not appropriate in synagogues, because again, they had no background, no religious education, no understanding of symbols, of religious language and iconographic language.”

While academic and state institutions had a hand in restoring these houses of worship, the movement was very much also community led. “You can’t do it just as an artist or as an art student, you have to have a larger support,” Teter said. She noted that in Kharkiv, where Kotlyar was based as a student, there was a large community of 40,000 Jews who were also involved in the push to reclaim and restore these synagogues.

Kotlyar began creating these stained glass windows in 1993 for a course project while a student at the Kharkiv Art and Industrial Institute. The first of his designs was for the Kharkiv Choral Synagogue, the largest in the country. In his opening remarks at the exhibition, Kotlyar described his moment of inspiration: “When inside, I raised my head up to where the dome was rising, and seeing the crumbling plaster, I said to myself, ‘Oh, I would create something like the Sistine Chapel by the great Michelangelo here.’” He designed two windows on the theme of Jewish holidays which would have run along the sides of the synagogue. The final result was unfortunately never implemented as it was lost to a fire, but his original designs and images are currently on display in Walsh Library. The exhibit features two additional designs by Kotlyar, one for a synagogue in Podil and another for one in Kyiv.

Nearly 20 years after the initial stages of the project, Teter and Kotlyar met through the aforementioned virtual fellowship program, which was instituted in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The fellowship extended to scholars and students of Jewish studies a space to continue their studies amidst the war, offering workshops and extensive source material through access to the Fordham and NYPL archives. “He is a very, very interesting person,” Teter said of Kotlyar, “because he’s an artist, he’s a designer, but he’s also a scholar of art history… And it’s a very interesting way to look at his work of how he is able to balance and combine both his scholarship, but also his personal commitment to Judaism, to reviving Jewish faith and Jewish community in Ukraine as well.”

It was here that Teter came across Kotlyar’s designs and arrived at the idea for an exhibit: “I looked at a catalog of his designs, and I was blown away — they were just beautiful, the stained glass windows was beautiful. And that’s when I said, ‘Okay, we have to sort of see how we can do it here.’”

“Putting together an exhibit is an extremely arduous process,” said Linda LoSchiavo, director of libraries at Fordham University. The exhibit is the second held in the Henry S. Miller Judaica Room, which was inaugurated less than a year ago. “It was much more complex than our previous opening exhibit last year. Our new layout offered challenges and opportunities, as we will be displaying items both inside and outside the room itself,” said LoSchiavo.

The exhibit is aims to be thoroughly historic as well as artistic, sharing with the visitor not only Kotlyar’s designs, but also the history of reclamation, restoration and return to roots for Jews in Ukraine at the turn of the century. In his opening remarks, Kotlyar introduces the exhibit to Fordham: “Displayed here are historical photos and designs of synagogues, sketches of stained glass windows, as well as photographs of completed works. Together, as artistic images in connection with a larger historical context, and from a broad perspective you can see… the first samples of stained glass designs from modern Ukrainian synagogues.”

Teter said she encourages Fordham undergraduates to visit the exhibit, even through a simple library study break. “Just, if you need a break, you’re studying in the library… go to the fourth floor to the Henry Miller Judaica study room. And just look at the beautiful images. And you can stand and look at just one at a time… You can engage with it at the historical level, but you can also engage with it in this sort of aesthetic level, and even a spiritual level.”