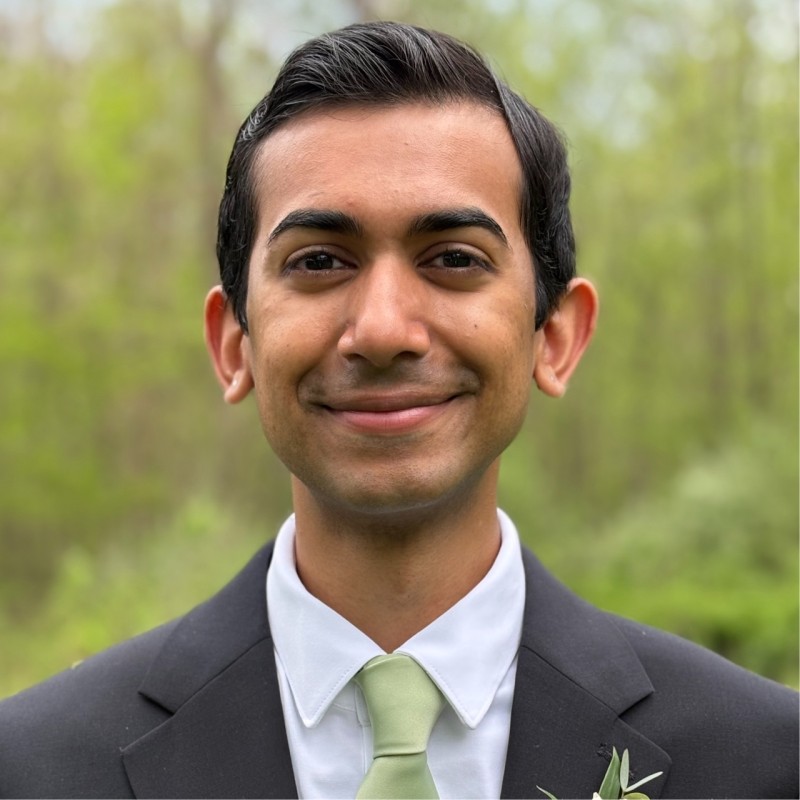

Over the summer, Christian Hidalgo, FCRH ’25, assessed the spatial association between public housing in the Bronx and ambient air pollutants. “I was looking to see if higher concentration of public housing was correlated with a higher emittance of whatever air pollutant,” Hidalgo said.

Hidalgo said that the Bronx is divided up into 12 different community districts. He looked to see which districts had a higher proportion of public housing, and then used New York City’s Community Air Survey to find data for emittance of air pollutants based on seasonality and yearly averages. This air survey, which has been conducted since 2012, uses air monitors around the city to observe the levels of a variety of air pollutants like PM 2.5, nitrous oxide, carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and ozone pollution across different parts of New York City.

The first half of Hidalgo’s research involved an in-depth analysis of the history of public housing, looking at why it was placed where it was. “I read a lot of literature on Robert Moses specifically, the infamous city planner; I read about him, I read about the Housing Act of 1939, and various other federal and city laws and regulations that affected where public housing was concentrated,” Hidalgo said. In this initial literature review, Hidalgo said he wanted to contextualize the impetus for this research and help others understand the current state of public housing. He said he also wanted to explain the importance of understanding this correlation and how it was the result of city and federal policies. In the second half of the summer, Hidalgo transitioned towards looking at the actual city data and trying to place his research within the larger implications of housing policy and environmental classism in general.

Although Hidalgo is still working on a final draft of his research project, preliminarily, he was able to see a large correlation between public housing and air pollutants. The community districts one and three had the largest proportion of public housing in the Bronx, and both of these districts primarily lie in the South Bronx. Hidalgo found a statistically significant correlation between many of the air pollutants and the concentration of public housing. This is especially compelling data particularly when considering the small sample size that Hidalgo was working with. When talking about himself and his advisor, Dr. Emily Rosenbaum of the sociology department, Hidalgo said, “At the end of the summer we were both shocked because it is a very strong correlation for the small sample size that I had, and the fact that a majority of them were statistically significant is also crazy.”

Hidalgo became interested in this issue of air pollution and how it plays a role within classism because of his upbringing in central California, where his hometown is the second-largest oil-producing county in the United States and has the third-worst ozone pollution and second-worst PM 2.5 pollution in the contiguous United States. However, in comparison to New York, the West Coast really does not have the same level of public housing, so when Hidalgo came to New York, he became interested in looking at the correlation between these two factors, since public housing is made for low-income people and families. “I have always been interested in air pollution and its role within different ethnic groups and socioeconomic status,” Hidalgo said.

In the future, Hidalgo said he hopes to examine this issue in all of New York City, not just the Bronx. Hidalgo also said he wants to show with his research that the typical method of public housing may not be the best way to go about creating affordable housing for lower income people. In the 1950s and 1960s, enormous public housing developments were created, destroying entire blocks. Hidalgo said he wants to draw attention that this may not be the most effective way to go about creating affordable housing; instead, integrating public housing into “normal” neighborhoods can be a mechanism of allowing access to affordable housing while not completely concentrating poverty in one particular area. On a broader scale, Hidalgo said he wanted to highlight the issue of environmental classism and just how many aspects of life it can touch and impact. “This has much broader implications in that poor people are just exposed to more environmental hazards in general because of city, federal, and state regulations, along with just where we push poor people,” Hidalgo said.