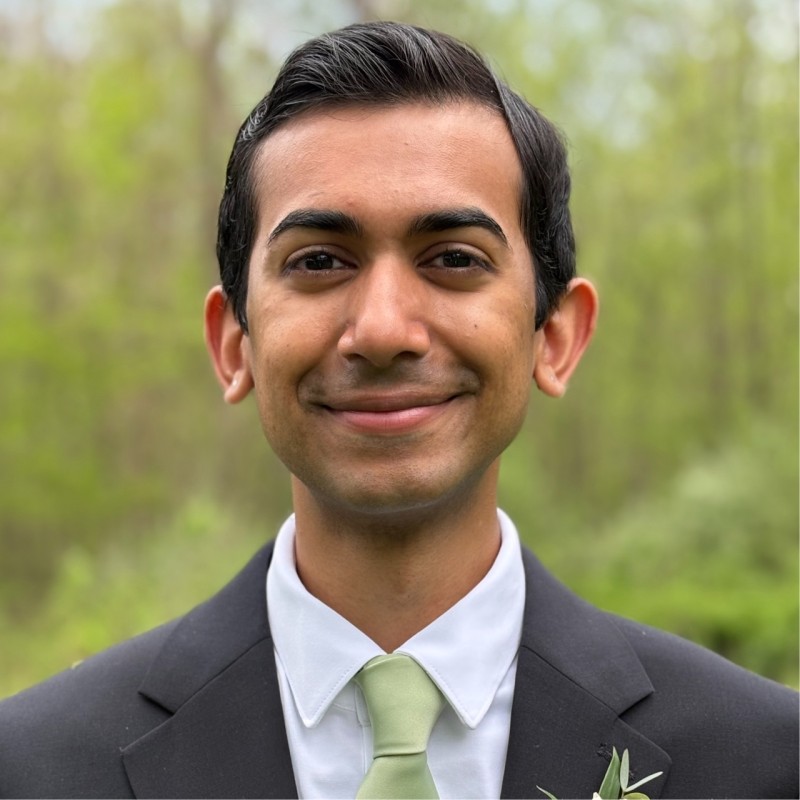

Christopher Ciaccio, FCRH ’25, spent the summer using philosophy and theology to answer questions about the capitalist world. Ciaccio is a philosophy major with a minor in theology. He worked with Brenna Moore, Ph.D., in the theology department. Ciaccio said he was inspired by “Capitalist Realism,” a book by Mark Fisher that focuses on issues of culture and neo-liberal capitalism in the 21st century. Fisher calls for an alternative to the economic, political and cultural order, but acknowledges the capitalist system’s power is that it makes it seem as though there is no other way.

Ciaccio said he wanted to ask, “Where can we find alternatives? Is it even possible to find alternatives?” These issues were the framework for Ciaccio’s project and inspired his research.

On a mysticism retreat with the Fordham Philosophy Society, Ciaccio did a lecture on two mystics, Simone Weil and Georges Batille. “I have loved Batille for forever,” he said. He said he was inspired to do more extensive research on the two thinkers in relation to each other. At first glance, they couldn’t be more different. Weil was an unbaptized Christian mystic with a strict moral code. Ciaccio called her a “paragon of morality.” Batille, on the other hand, drank heavily and frequented brothels. However, both philosophers had mystical experiences as well as political projects, and were prolific writers on these subjects.

Weil and Batille lived and published in an age of 20th-century capitalism, trending toward industrialism, far-right ideology, consumerism and secularism. Ciaccio said he believed they were “addressing similar problems to the ones we have in the 21st century,” and drew connections to Mark Fisher. “A lot of traditional ways of being were replaced,” he said. In an attempt to explore ways of living counter-culturally, and getting around the seeming inevitability of capitalism, Ciaccio began to read and study these two authors and their perspectives on “new ways of being in the world that aren’t mediated by capitalism.”

Weil, a communist turned Christian, was so committed to a “complete rejection of material pleasures” that she abstained from sex, drinking and became so anorexic that she was unhealthy for the rest of her life. While Weil was a model of self-denial, Batille was focused on self-indulgence.

However, Ciaccio saw the parallels between their thinking. Both mystics identified a problem in society — “the sacred” as a concept was no longer present. “Their solutions are different,” he said, “but they both involve a reintroduction of the sacred.”

One of Batille’s solutions was the formation of a secret society, Acéphale, whose goal was “creating new myths and sacred things.” The society involved strict rules and human sacrifice, though the latter never occurred. Batille also emphasized writing and meditation in his attempt to “create new stories” for society. Weil was well known as a political activist, and frequently participated in and organized anarchist marches. Once, when she was eight years old, her parents lost track of her on vacation, only to find her in the hotel lobby convincing all the hotel workers to unionize.

Weil had terrible health all her life, but throughout her migraines and physical pain, she found a spiritual connection to God. Ciaccio said that for Batille, “mystical experience was also tied to self-destruction.” In his book “Inner Experience,” Batille talks about laceration and about cutting off parts of life that are not serving the inner spirituality. His first mystical experience came when meditating on a picture of someone being executed through the method of death by a thousand cuts. Weil voluntarily worked in a factory with horrific working conditions so she could experience the pain of working class people. She wrote that this experience made her feel like an object in an assembly line, but she believed it was deconstructing the part of her that was herself and leaving only God.

Ciaccio’s research ultimately focused on what these two thinkers had to say about alternatives to capitalism. Batille wrote a book called “The Accursed Share,” in which he critiques the post-World War II Marshall Plan. His thesis is that as organisms gather energy and use it to sustain themselves and grow, there will always be some wasted energy, and that portion is the accursed share. Batille hopes to avoid war and violence, which would result in more wasted wealth and energy, and thinks that there should be an alternative to the Marshall Plan. In Weil’s book “The Need for Roots,” she claims people are lost in work, without a past or future. She also writes in “Waiting for God” about the concept of attention: a meditative state where one empties oneself out and “turns towards the other.” Ciaccio said this is Weil’s most important solution “in a society where we are more separated from each other than ever, more atomized than ever.” Ciaccio says he sees this as a remedy for the mindlessness of everyday life — it is “forcing you to be conscious.”

He also emphasizes Weil’s argument that we should not be treating other people as objects.

Ciaccio wrote a secondary literature article on Weil and Batille, and is currently in the process of editing his work to publish it.