My Testament for Those With Impostor Syndrome

Going into my first year at Fordham University, I knew I had to be one of the stupidest admits.

I scored a composite 29 on my ACT and ranked just over the 25% percentile of standardized testing for the university. While I should have been happy to be offered a place, instead, I was filled with fear: how was I going to match up to everyone else? How could I be sure I wasn’t going to completely fail? Of course, I had no idea what my time at Fordham was going to be like, so I had no choice but to go $30,000 in debt trying to find out.

I come from a low-income, Hispanic-majority seaside town in New Jersey, where the beach is the only thing that isn’t underserved. The coast is covered with million-dollar beach homes owned by New Yorkers and the inner city is held together by pieces of tape. I love my city and, growing up, I saw nothing wrong with it.

When I came to Fordham, I thought I had a working class childhood; my new classmates showed me that, in fact, I basically lived in abject poverty. Culture shock wasn’t the word — I was surrounded by girls donning Cartier bracelets and Montcler jackets, boys with Rolex watches and a strict diet of Polo Ralph Lauren. The first time I thought about dropping out was during orientation week.

It became very easy to think little of myself. With my first two semesters on Zoom, I spent a lot of time in my own head, convincing myself that I wasn’t doing or being enough. When I completed my first round of finals in college, I remember being clouded with disappointment in myself, a feeling I know I would have felt regardless of how I performed. Nonetheless, my grades were less than my high-school-usual of straight As, and I had to put on a painted face as if it didn’t absolutely cripple me.

I came back the following semester and accomplished even less, struggling with a myriad of problems in my personal life. Nothing felt real. I over-burdened myself with an internship and felt even more like a disappointment because I couldn’t force myself to do what my brain wanted. I was exhausted. I made arrangements to transfer, whether it be to a lower-ranked school or in a completely different country, where I didn’t know anyone. An identity change is what I wanted, so I could pretend that everything I did in my previous year at Fordham never actually happened, and I wouldn’t have to claim responsibility for it.

A dean reached out to me, seeking to discuss why I wanted to leave the university. When I agreed, they never followed up.

In short, I felt abandoned and alone. Abandoned because I felt like none of the resources at the university could make me feel better, and alone because my friend group was small and restricted by the pandemic. I sought to be known, to be truly understood, to meet someone like me: smart but not virtuous, plagued by similar financial anxiety and insecurity. I was worried that these shortcomings started to define me, as I would slip them jokingly into conversation as a way to cope and make them seem less scary. When I looked at myself, I saw what I thought everyone else did: the girl too dumb and too poor to attend Fordham.

Summer was transformative for me. I was accepted as a resident assistant — then halting my transfer plans — and escaped a toxic, terrorizing friendship, which prompted me to start therapy. While it was not one quick fix, I began viewing everything in a different light. I got high grades in my two summer courses and it was the first time I was proud of my academic achievement in years. I worked 28 hour weeks on top of my classes to give myself a sense of financial stability. When I returned this past fall as an RA and a member of the pep band, which began to meet in-person, I started to feel like I was a part of something again. I started to feel like I belonged.

I eased into our latest fall semester with some apprehension, but it exceeded all of my expectations. I became closer than anticipated with my building staff, started to sincerely enjoy being a musician again and didn’t feel completely burnt out from all of my classes — except for Spanish. I felt as though I was coming back to life and I was excited for subsequent days and weeks of what the school had to offer me, which I never thought would happen. I don’t know what would have happened if I transferred to somewhere else in the country, moved overseas or dropped out entirely. I can’t say if I would be better off than I am now. But I know now, in a spring semester where I have tacked on the responsibilities and found microcosms of community in every one, I am thankful.

The insecurity has not disappeared, but I have been able to push it to the backburner. I still have painful flare-ups of shame when I think about my spring GPA of 2.9 or the fact that I have two C+s and a W on my transcript. I fear for the future, whether I choose graduate or law school, how that may go over with admissions officers or how I may handle the debt.

I am writing this because I know I am not the only person wondering if things would have been better had they never stepped foot in The Bronx. I am writing this in the hopes that it serves as some kind of encouragement, solidarity and act of faith. I have so many people to thank for helping me feel at home, but I mostly have to thank myself for being able to quiet that little voice in my head and push forward. To the person reading this, if you’re feeling kinship with my freshman self, I hope you know that it does not feel like that forever. There is more to life than the titles you impose on yourself and there is still greatness unforged.

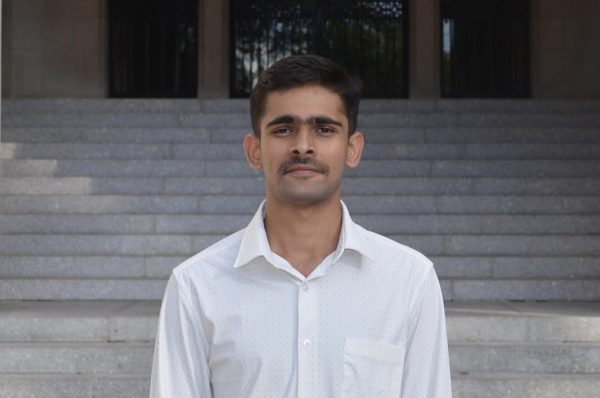

Samantha “Sam” Minear is a senior from Long Branch, N. J., majoring in international studies and communications. She started as a contributing writer...

Maureen Segota • Feb 14, 2022 at 10:16 am

Well done Sam! Your story will serve as inspiration to others feeling similar to you. The strength it took to put these words “on paper” is admirable! I imagine you feel liberated and I’m happy for you!