Are You Listening Yet?

We usually think of mass incarceration in terms of the 2.3 million people locked in U.S. prisons and jails. They account for 25% of the world’s imprisoned people, despite the fact that America makes up only 5% of the population.

However, according to the scholarship of Michelle Alexander, if you include people on parole or probation, the number is more than three times higher. This means one in every 31 adults is actively participating in the criminal justice system. Beyond that, Alexander writes, 65 million people have criminal records in the United States, all of whom face legal discrimination that stalks them for the rest of their lives. Alexander wrote that people with criminal records are disallowed from public housing, food stamps, jury service and in most cases the right to vote. Additionally, those same people are presented with incredible difficulty finding employers that will hire them.

If you extrapolate here, it is very reasonable to conclude that at least 100 million people have been directly impacted by this deliberate state and federal policy.

It’s also no secret that all of this is racist and that it developed directly from racialized chattel slavery, which is, of course, why Alexander’s book is called “The New Jim Crow.”

Prison has certainly become more American than apple pie.

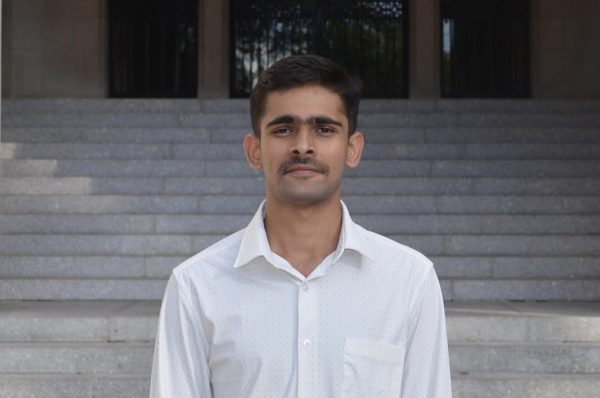

Yet, we don’t talk about it; we’re afraid and embarrassed to discuss whether or not people we love have been to prison. I’m speaking from experience here. It took me years to reach a place where I felt safe telling people my dad spent years in prison before I was born. Over and over, this led to social isolation and insults if people found out. That’s why many people who have known me for years don’t know this.

But it was not until I found the strength to openly discuss this that I began to comprehend the magnitude of the carceral state. I realized it could not be understood in terms of statistics. Any ability to grasp this has to be rooted in people’s stories, the stories of the people our society throws away. That’s why in the last year, I have spent a lot of time writing to prisoners. I’ve developed some incredible relationships and found myself on the verge of tears perpetually. But I have never been more grateful.

I want to encourage others to write to people in prison. It is such a small thing, but it can be so transformative.

We’re not supposed to do this. The architects and champions of mass incarceration will tell us these are “superpredators,” people we should fear, fear enough to spend billions of dollars every year to keep them in cages. But I’m here to say that’s not so.

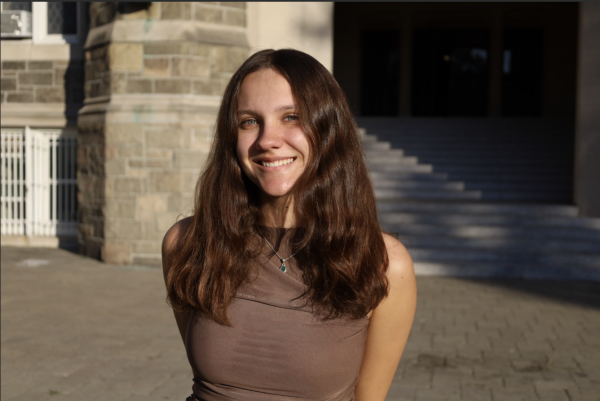

One of my closest relationships during the pandemic has been with an incarcerated person. Their name is Justin Kaliebe; they will be 26 in November. We all call them Just. Like my dad’s family, they are from Long Island. When they were 16, they began exploring Islam and met an older man named Waleed at a mosque. At this time, they were struggling mightily with family issues, as so many of us do. They are also mildly autistic. Over time, they developed a very close relationship with Waleed, one of the few people who showed any interest in them. Shortly after their 18th birthday, they were arrested at JFK and charged with giving Islamic terrorists material support. It was not until they were in court that they learned Waleed was an NYPD operative who worked with the FBI to build the case.

That was in 2013 — Just will not see the “free world” again until 2024. While we call it entrapment or child abuse, the state calls it national security.

Just and I are both interested in journalism; we both want to give voice to voiceless people. This summer, I started publishing their writing on Twitter using #PrisonsKill, which Just envisioned. Just’s first essay was about a friend who dealt with intense medical neglect after being diagnosed with syphilis at MDC Brooklyn, where Just spent the first years of their bid. We recorded it over the phone and it was aired on WBAI, where I was interning at that time.

But we were in the middle of a pandemic. The prison where Just is, which is in southern Georgia, close to where Ahmaud Arbery was murdered, was consistently on lockdown. First it was because of the pandemic. Then they transitioned into total lockdown, along with every other federal facility, because of the protests following George Floyd’s murder. For a week, there were no calls or letters.

In July, the lockdown predictably proved pointless. The virus made its way into the facility. 95% of the unit tested positive. Just reported stabbing pain and an inability to taste food, but they survived.

At this point, the phone calls basically stopped. I’d get letters sometimes with essays to post, sometimes not. In early August, Just was taken to the hole. There was an “investigation,” the prison said. One of their outside contacts, they were told, might have ties to antifa. I only got one letter while Just was in the hole; it was written in pencil because they don’t allow prisoners in solitary to have pens. When I read the letter, all I wanted to do was go to Georgia and give them a hug.

Just was briefly let out of the box in August. But by the last week of the month, they were back in. We think the prison is retaliating because Just spoke out about the fact the unit became a Petri dish. On Friday, Just will have been in the hole for 28 consecutive days. The United Nations says more than 15 days is torture. When I called the prison administration to express this concern, they told me that they don’t follow that. There are no limits to how long people can be held in solitary.

Essential medical treatment has been denied, letters are being censored. One day I got five letters sent back to me, the prison cited a “security risk.” The letters contained writing by other incarcerated people I know, people that were inspired to write by Just.

I can tell you that fear runs through me every day. I can tell you that I check my post office box each afternoon, hoping for a letter and that there has only been one since I’ve moved back here. I can tell you this is wrong. But you shouldn’t listen to me.

This is a moment where the uprisings are calling us to imagine new social relations, new communities, new ways of being. People are calling for the end of the carceral state, the extinction of the prison industrial complex, the abolition of the police. People are calling for a revolution in this country.

All I want to say is listen. Listen to those who are on the other side of the wall. You can read what we’ve been publishing. You can listen to and read the work of jailhouse journalists like Mumia Abu-Jamal and Kevin Rashid Johnson. You can listen to your friends and relatives who have been locked up.

In Kenosha, Wisconsin, where the police shot Jacob Blake seven times in the back, the Department of Corrections was burned to the ground. Amidst the wreckage and debris one wall remained standing. Someone brave and beautiful used this as an opportunity to pose this same question in black spray paint: “Are you listening yet?”