By Joe Moresky

With so much political unrest surrounding the 2016 presidential campaign and its operation, it may be prudent to examine the nature of our electoral system and evaluate its pros and cons. The United States operates under what is known comparatively as a plurality system, where a “winner-take-all” approach is utilized. Operating on the existence of single-member constituencies, a plurality system awards victory to the candidate that earns the highest percentage of votes in a race — even if that share is less than a majority. While at first glance this may seem like a terrible setup for a democratic nation, in reality it merely reflects a different understanding of democratic rule.

And that’s not a bad thing.

The defining principle dividing different forms of democracy is the answer to the question of who ought to rule. Electoral systems are no different, with varying answers having profound effects upon a government’s structure. Plurality systems contend that the majority of the people ought to rule, an assertion manifested in its “winner-take-all” structure. Naturally, this answer dramatically impacts a voters experience with democracy.

Plurality systems are among the easiest electoral systems to understand. Results can be reported fairly quickly and the adversarial nature of the system means a clearly defined winner is apparent to voters. Citizens can easily identify who has been in power — and therefore who to hold accountable.

Additionally, the high potential for seat turnover is a prime motivator for elected officials to remain responsive to the concerns of the public. Plurality systems tend to result in landscapes in which only two parties are dominant, a phenomenon known as Duverger’s Law. The “winner-take-all” structure of the system leads to the extermination of lesser third parties or their absorption by larger, more successful parties. Since opposing ideological bases are covered, the pursuit of the median voter dominates political discourse as only a small change in voting percentages is enough to transfer the responsibility of governing to the opposing party.

This places immense power in the hands of the voter, for although governments are given more unilateral power than in competing electoral systems, this power can be checked by a modest shift in electoral outcomes.

The focus on median voter blocs also produces a strong incentive for parties to further moderate policy agendas as they compete for the center (i.e. as many voters as possible). This in turn encourages stability and cohesion within the government, as radical change in either ideological direction is unlikely.

While not perfect, plurality electoral systems offer a large suite of advantages to democratic nations. If electoral reform is needed here in America, it would be wise to not throw out the baby with the bathwater.

Susan Anthony • Apr 27, 2016 at 3:41 pm

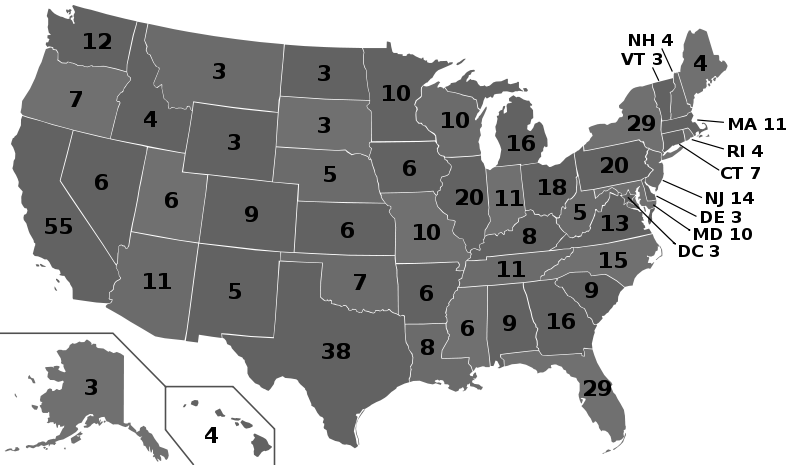

New York has enacted the National Popular Vote bill. It would guarantee the majority of Electoral College votes, and thus the presidency, to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in the country, by replacing state winner-take-all laws for awarding electoral votes in the enacting states.

Every vote, everywhere, would be politically relevant and equal in presidential elections. No more distorting and divisive red and blue state maps of pre-determined outcomes. There would no longer be a handful of ‘battleground’ states where voters and policies are more important than those of the voters in 38+ states that now are just ‘spectators’ and ignored after the conventions.

The National Popular Vote bill would take effect when enacted by states possessing a majority of the electoral votes—270 of 538.

All of the presidential electors from the enacting states will be supporters of the presidential candidate receiving the most popular votes in all 50 states (and DC)—thereby guaranteeing that candidate with an Electoral College majority.

The bill has passed 34 state legislative chambers in 23 rural, small, medium, large, red, blue, and purple states with 261 electoral votes. The bill has been enacted by 11 small, medium, and large jurisdictions with 165 electoral votes – 61% of the 270 necessary to go into effect.

NationalPopularVote.com