Feminism: It’s the Final Frontier

If you already hate this article based on the title, I get it. Every time I read an article about “sexist geeks” written after 2010, I have to roll my eyes. For one, if you’re talking about sexist geeks, you’re either talking about an imagined enemy faction, or random dudes with hobbies. And we have a word for random sexist dudes with hobbies. We call them sexist men.

“Geek” was hardly an identity to begin with, and it’s even less of one now.

It’s no secret that the idea of “subculture” as we know it is on its last legs. Punk is dead, hipsters faded out and TikTok is currently beating the corpses of scene and emo. Everything happens so much, and it happens too fast for a subculture to really take root. Popular “geek” culture today — in this article, I’ll be focusing mostly on the genre of science fiction — is nothing but a shallow expression of empty and wasteful commercialism. It’s dull and lacks any sort of originality or willingness to build on what it has created. The whole scene, or what remains of it, is built on a tower of Funko Pops.

All of that, and it still manages to keep its reputation for sexism. A reputation that is still not entirely undeserved.

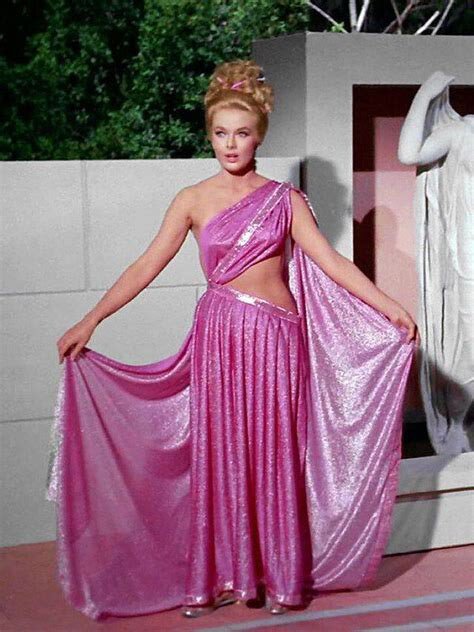

There’s a reason the Golden Age of science fiction focused so much on sex (for the ’50s, anyway). It was a natural pushback to the puritanism of the major pulp magazines, up until John Campbell’s tenure as editor in “Astounding Stories of Super-Science,” better known as “Analog Science Fiction and Fact.” Once Campbell took over, readers would see fewer beetle-like aliens on the cover and many more bodacious babes. So sure, science fiction as we know it was built by women. Women marketed to men and boys. Women as objects, eye candy, damsels, miniskirted captains, demure android maids and Venusian vixens. Women as a simulacrum.

I’ll say this in fewer words: the fundamental works that the genre is built on display an abundance of females, but revel in a lack of women.

As much as people will cite Mary Shelley as the first science fiction author, I find this to be an unfair copout to a very valid criticism of the devaluation of female voices in the genre. No one hears “science fiction” and thinks of Frankenstein’s monster hiding in the woods and learning French. The images that come to mind — rayguns, outer space, scantily-clad women being abducted by aliens — are more likely to hail from the pulp magazines of the 1940s and ’50s.

And if the average person on the street can recognise Ursula K. Le Guin for the icon she is, I’ll eat my shiny silver space helmet.

They are far more likely to think of Dick and his audacious usage of the term “melons,” Asimov the dirty old man, Roddenberry the womanizer, Heinlein and Bradbury, the patron saints of tunnel vision and archetypes. Ellison the … well … Ellison. Men that are better able to relate to aliens in their fiction than they are able to relate to women in their everyday lives.

Honestly, it’s fine that the original Star Trek is sexist sometimes. The Theiss Titillation Theory wasn’t coined for nothing. It’s still quite progressive for its time, and I can’t necessarily say the insistence of having women in skimpy outfits for the precious male demographic is enough to take away from its genuine contributions to the genre. Sure, Asimov’s Dr. Susan Calvin is described multiple times as being “homely,” and this is used to mock her, but I was genuinely excited to find that Asimov had deigned to have a female character be a scientist at all, let alone an authority figure. Every time Hienlein decides to have something horrible happen to a helpless woman just because, I can look past it because the work is just that good.

The issue with the sexism in these properties is the way in which everyone absolutely refuses to acknowledge any tarnish on their golden calf.

The classics are a product of their times, which I have no problem with. My problem is with the expectation that women are simply being petulant when they are uncomfortable with the way the genre’s most beloved works treat them. Because what was in the past is never contained to the past. Science fiction is a self-referential genre it has its own tropes and themes and cliches to call on. It constantly regurgitates the classics of the past. These works don’t just go away. Any woman that wants to get into the genre gets these authors recommended to them. It’s only fair that she gets to call it like she sees it.

Hasna Ceran, FCRH ’23, is a Middle Eastern studies and economics major from San Jose, Calif.

Hasna Ceran is a junior double majoring in economics and Middle East studies. She began by writing the USG Column for Volume 101 and served as an Assistant...