Self-Growth, Self-Understanding and Reflection in the New Year

My New Year’s Eve this year was anything but spectacular. The omicron variant was conquering my city and hometown, so I watched the ball drop with two of my high school friends in one of their basements. And, while my celebration of the new year was mundane, I still left my friend’s house with the thought I have every year: what will I do differently?

The idea of making New Year’s resolutions has always slightly irked me. It may sound pessimistic, but I have honestly never understood the point or reason for New Year’s resolutions. Why do we only make resolutions at the beginning of the new year? How much can a person change from Dec. 31 to Jan. 1? Why is it so much more appealing to people to make a resolution at the beginning of the year than halfway through the year? What is the point of resolving to eat healthier only to pick up the same eating habits when Christmas break ends, and you inevitably get too busy to cook and fall back into the same eating patterns? Why would you resolve to work out, only to realize how cold it is in January and how unappealing going to the gym is when it gets below 30 degrees? Why resolve to spend less time on screens only to realize that half the world operates online now? I know this sounds overly cynical, and maybe it is, but I speak from experience.

New Year’s resolutions are not just contemporary practices. The ancient Babylonians are thought to have made the first sort of New Year’s resolutions nearly 4000 years ago. They would reaffirm their loyalties to old kings, return anything they had borrowed from the year prior and make promises to the Pagan gods. They thought they would be gifted with good fortune from the gods the following year if they kept their promises. In Ancient Rome, Julius Caesar changed the calendar so the new year would begin on Jan. 1. The Romans then engaged in promising good behavior in the upcoming year. Interestingly enough, they would pray to the god Janus, who they believed to be a two-headed god who looked forward into the new year and back into the past. The name “January” can be traced back to Janus, which means “beginnings and transitions.”

That’s all to say that the idea of New Year’s being a time of self-reflection and change is not new; in fact, it’s ancient. For the last few years, I have struggled to make a resolution. In 2020, I was a senior in high school, and I was going into the year with no idea where I would go to college or where I would be at the end of the year. I didn’t feel like making a resolution was even possible since the trajectory of my life was so unclear. How could I possibly make a goal when it felt impossible to know if I would be in place to uphold it in a few months? As it turns out, the unexpected did happen that year. In March, COVID-19 shut down the world.

The world still seemed unclear going into 2021. COVID-19 cases were picking up, and even though the promise of mass vaccination was on the horizon, it still felt too far away for me to get excited about it. I had become comfortable at Fordham to a certain extent, but I was still a lost freshman in many ways. I had just joined the Ram staff, which I was excited about, but I had never even stepped foot in the office or met any of the other staff members in person. In lots of ways, I felt totally disconnected from the entire operation. Last year, I didn’t think I had enough direction to formulate resolutions or goals since my understanding of myself and what I was doing was low.

However, when I left my friend’s house this year, I felt slightly different from the past two years. The idea of making a resolution seemed a little less daunting. As a sophomore, I have much more of a grasp on my life and myself than in years past. I realized on that cold and dreary walk back to my house on New Year’s that resolutions can be small. They don’t even have to be tangible goals with visible results.

In American society, we tend to praise self-improvement incessantly. The entire unrealistic American ideal of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps” relies on the idea of being able to improve your situation independently and visibly. In the U.S., I’ve noticed that we tend to praise self-improvement for changes that people can see. We applaud people that can get in shape. We praise those who get a big promotion or pay raise. We love to see people who change their career paths and are widely successful. While I’ll admit all those things are worthy of praise, so are other feats. Making an effort to improve yourself mentally in small ways or making time every day to do something you enjoy are good resolutions. But for some reason, these things aren’t as applauded as being able to talk about how you haven’t eaten processed sugar in 30 days. For lack of better words, pulling your mental health up by its bootstraps is much less impressive than getting a job promotion.

For me, it took understanding that a resolution’s scope doesn’t have to be so obvious to see the value in them. This year, I want to improve myself continuously. Not because I dislike myself, but because I think always striving to be a little bit better every day would make me happy. For me, that’s a doable resolution. It’s a resolution not measured in any metric other than how I feel every day. I know there will be dips and climbs throughout the year. I understand that this resolution will not radically change my life, nor will I feel drastically changed at the end of this year. I know that thinking like this will help me have a better year, which honestly is one of the primary purposes for making a resolution in the first place. But I also know that if I make a resolution in July, it will be just as valid as one made in January.

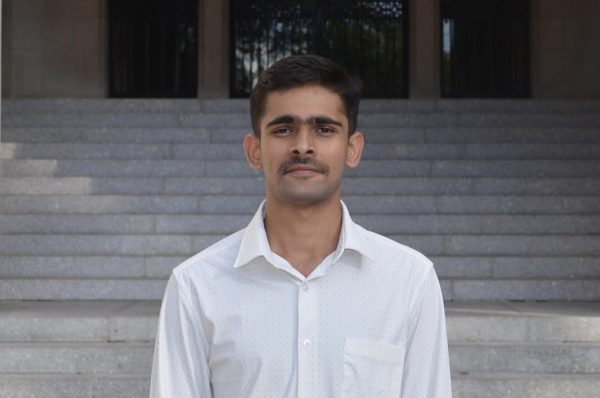

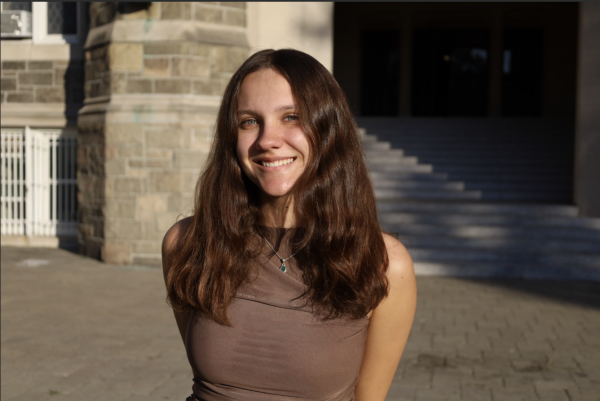

Isabel Danzis is a senior from Bethesda, Md. She is double majoring in journalism and digital technologies and emerging media. The Ram has been a very...