The Everlasting Value of an English Degree

As a current college freshman and journalism major, I am often told the “unfortunate reality” from my peers that there is simply no money in an English degree. Even when my dentist asked what I was studying, I was immediately met with the statement that I will “definitely change my major.” The amount of times I have heard these doubtful proclamations has made me ask myself: Is there still value in an English degree? Although English and history degrees continue to decline as the STEM field persists in its expansion, the merit of an English degree will never fully disappear.

The English degree is constantly bombarded by the claims that the major is simply useless. When contemplating the value of a degree, students typically analyze one factor: How much money will I make? Pamela Paul, New York Times opinion columnist, states that students may have begun to steer clear of English degrees because of “astronomical debt” and an “uncertain job market.”

Why is this job market seemingly so uncertain? As a society, we have worked to deface the power and meaning of English-related majors by preaching that jobs in STEM and business fields are much more useful and lead to more success. These practices inevitably neglect the students whose true talents lie in the humanities, and consequently place doubt in the prospect of this degree. I myself have fallen victim to this doubt, often contemplating whether or not I should switch my major.

When I fall into this trap, I remember a few things. First, I am not objectively “good” at science, math, technology or engineering, so I should aim to accomplish something that I am genuinely interested and skilled in. Second, Paul belives that an English degree can offer many skills that are useful in the working world, such as being “intellectually curious, truth-seeking, undaunted by unfamiliar ideas and able to read complex works and distill their meaning in clear prose.” These skills are not homogenous, and are also important for science or technology majors to have; In fact, Amit Basu, an associate professor of chemistry at Brown University, states how being able to communicate effectively is a crucial part of science.

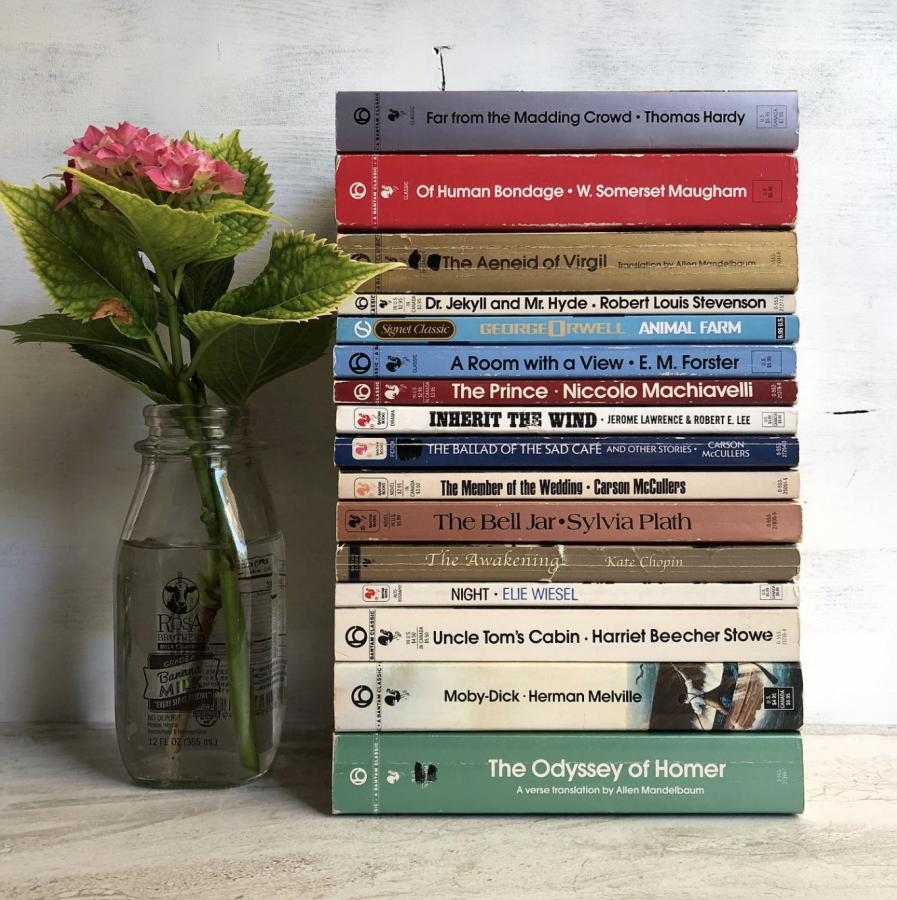

If these versatile skills are not useless and can be applied to many different fields of study, why does society no longer value them? Although a bitter truth, this is most definitely because of the absence of financial security. If students are continuously told that what they choose to study is a dead end in terms of salary and job opportunities, they will undoubtedly avoid the humanities track. There needs to be a slight disconnect between education and employment. Granted, we should focus on our post-grad goals throughout our college years, but we should also recognize that every major has its own value that is separate from its available job prospects. If everyone thought of their degrees as a pipeline to becoming rich, we would have way too many doctors, engineers and business-people in the world, and not enough intellectual thinkers, authors and educators. Think about the textbooks that we read for our educational courses, the television shows we watch almost everyday and the books we read on the beach — we would not have any of these things without those who chose to study an English-related major.

Similarly, why do college students still choose to major in the humanities when society preaches its capitalistic insecurity? In my opinion, the answer to this question lies in the need for a well-rounded education, along with the trust and passion students put into their educational paths. Deborah Fitzgerald, professor of the history of technology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, affirms that looking at college as a mere job training process poses an “obvious threat to higher education.” In other words, focusing on only one skillset or one subject inherently strips one of a balanced education; college should be viewed and practiced as a learning experience rather than a prerequisite for employment. With this mindset and an effort to reconstruct the value of skills related to the humanities, the merit of an English-based degree can be re-established. However, if you still have doubts about the use of an English-related degree, I will check back in four years to let you know how it’s going.

Ava Pastore, FCRH ’26, is a journalism major from Broomall, Penn.