Remembering Jimmy Hayes

Boston hockey standout Jimmy Hayes passed away for the most unfortunate of reasons, bringing light to a growing problem in America but leaving behind a legacy that shines beyond it.

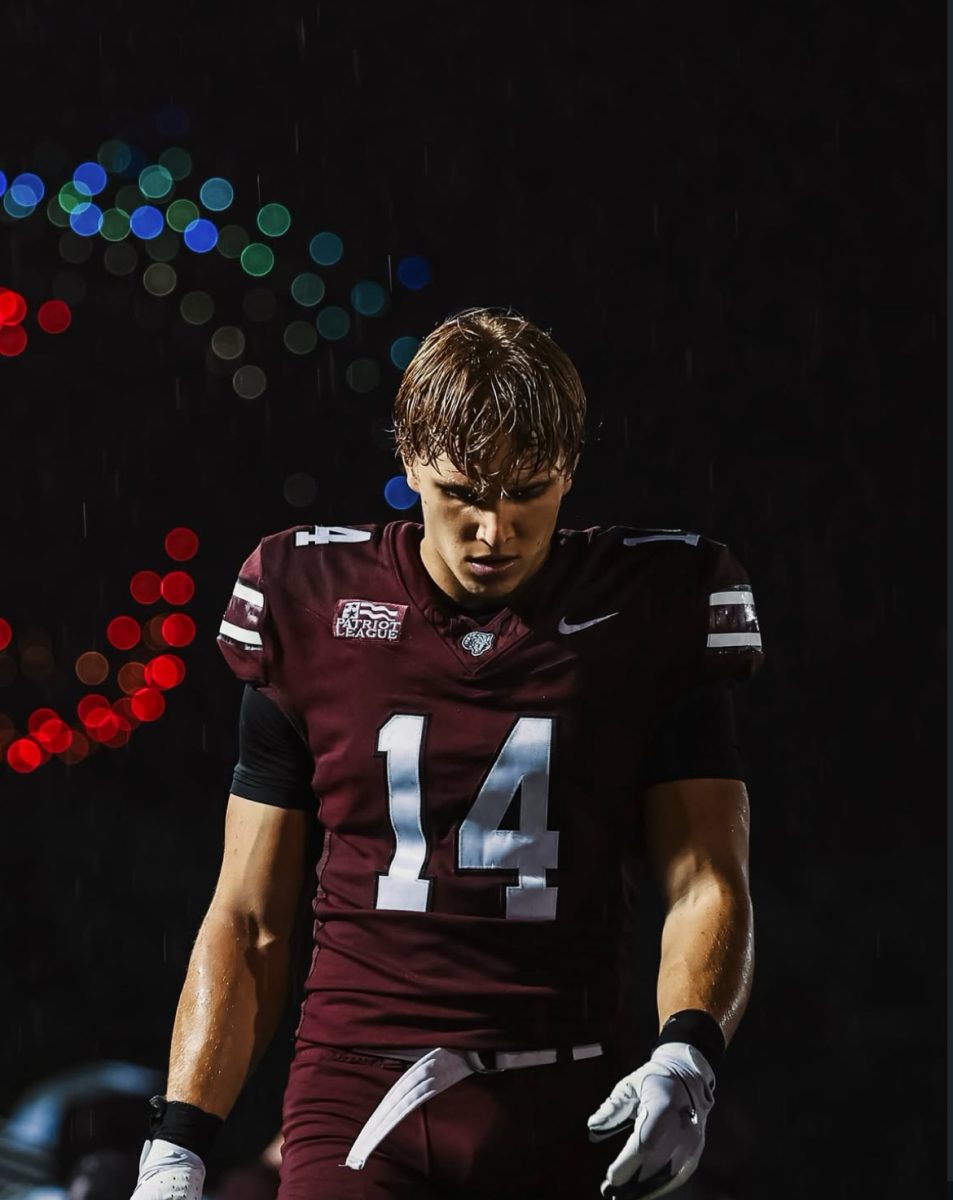

James Ryan “Jimmy” Hayes lived the dream of every kid that grew up playing sports. Born and raised in Boston, Hayes attended Nobles and Greenough Academy in Dedham, Mass. and Boston College, where he won a national championship in 2010 playing hockey. Although originally drafted by the Toronto Maple Leafs in 2008, he made his NHL debut in 2011 with the Chicago Blackhawks. Thus began a respectable NHL career that spanned eight years, 334 games and four teams, including a stint with his hometown Bruins.

Jimmy’s impact was felt throughout the ice. There are many testaments to his character as a teammate and a member of the community. He grew up on Westglow Street in Dorchester. Youth hockey was first played in Charlestown, then in Dorchester. Devine Rink on Morrissey Boulevard was home ice.

Jimmy and his brother Kevin quickly grew into local legends. Boston and former Yale University hockey standout Michael Doherty said that “growing up, Jimmy and Kevin were always the older local and national superstars that everyone sort of followed.” The two brothers went on to play together at Boston College. In a playoff game during their championship run, Kevin assisted Jimmy on what he called his “dad’s favorite goal.”

Jimmy stayed grounded despite all this success. Doherty, who is several years younger than Jimmy, remembers him as “always having the time to talk.” “With his pedigree,” Doherty says, “[Jimmy] certainly didn’t need to ask me questions about my career and family, but he did.”

Stories like these have surfaced everywhere since Jimmy’s passing this August. Stories about his positive outlook even in the face of healthy scratches. Stories about him staying late during Halloween and Christmas visits to Boston’s Children’s Hospital. Stories about him popping up at youth hockey practices in Dorchester. Even after retirement, he brought the same joy and energy to his next endeavor: fatherhood. Fellow Massachusetts NHL product Ryan Whitney remembers his approach best: “I’d run into him and [he’d] be like, ‘How cool is it being a dad?’ He loved it. He lived for it.”

The news of Hayes’ death hit the hockey world hard. The recent news that his death was due to “acute intoxication due to the combined effects of fentanyl and cocaine” hit even harder. For the past decade, Massachusetts has been on the front lines of America’s opioid crisis. As of 2018, it possessed one of the leading opioid-involved death rates in the country.

At first, such a fate befalling Jimmy seems unfathomable. In a recent article with the Boston Globe, his wife Kristen echoes this sentiment. “I was completely shocked. I was so certain that it had nothing to do with drugs … He never showed any signs of struggle at home.”

Hayes’ father, Kevin Sr., offers a different story, more in line with the reality of the national opioid crisis. In the same Globe article, Kevin Sr. says, “About maybe 16 or 17 months ago, I saw a little change in Jimmy’s behavior and I went to him and I said, ‘I think there might be a problem here with pills’ … he’s 31 years old so I can’t tell him to go get help. So I said, ‘When you want help, I’ll be here for you, pal.’”

Jimmy showed signs of improvement. He reached out to his father several weeks after that conversation and checked himself into a treatment center in Haverhill, Mass. However, as Hayes Sr. is familiar with — he has been in recovery for alcoholism for several decades — the disease of addiction is unrelenting.

It is one of those things that lies dormant inside. Then something happens, be it a sports injury or an auto accident. People are then prescribed opioids like vicodin, percocet or oxycontin to manage pain. They become addicted to their prescription, and when it runs out, they begin to search elsewhere.

Chris Young, M.D., Medical Director of Wellmore Community, Mental Health and Addiction Services in Waterbury, Conn., describes the physical sensations of the addiction process.

“When people use, they can feel sensations of energy, euphoria, analgesia and a general sense of well being. As addiction develops, they get to the point where they don’t feel normal unless they have the drug. During periods of withdrawal, they can feel feverish, fatigued and develop strong sense craving for the drug.”

This craving drives the risky, sometimes criminal behavior normally associated with addiction. Young recalls a story of a mother he saw in treatment who left her infant in the car on a hot day while she went to buy drugs. Upon receiving treatment, the mother was horrified at her own actions, which she thought to be no big deal at the time.

Addiction is not a choice. It is a disease. Those that are genetically predisposed to addiction have to grapple with it for their lives. “Relapse is pretty par for the course during recovery,” said Young. Some learn to manage this part of who they are and live with it. Others can spend their entire lives in the cycle of relapse and recovery. Unfortunately, there is a portion of the population that does not survive the relapse, namely due to the proliferation of fentanyl into the illegal drug supply.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opiate similar to morphine in how it affects the brain, but has nearly 50 to 100 times the potency. The opiate’s synthetic nature makes it easy to produce in a lab, which means the only limits on production are chemical supply and a safe location.

While it was originally mixed with other drugs, it now is sold outright. “Up until 2 years ago we only saw heroin,” said Young. Now, “9/10 of drug screens in Waterbury are positive for fentanyl and not heroin.” This uptick in fentanyl presence greatly increased the likelihood of overdose.

Because of the drug’s potency, users are more likely to misjudge their tolerance. This chance for overdose is even higher in the case of individuals, like Hayes, who just underwent treatment.

Michael Leslie is the Outreach and Development Coordinator of the Connect2 Recovery Program at Riverside Community Care, a Boston Area behavioral and mental health organization that utilizes local engagement to provide support services for families. A recovering individual, Leslie knows firsthand the challenges of addiction. “The thing with addiction is it does not discriminate. It can affect anyone, of any background, rich, poor, city, suburbs, whatever.”

This is how someone like Jimmy Hayes, a 31 year old former NHL player, who was a son, a brother, a husband and a father lost his life. However, addiction did not define Jimmy. Throughout his life and career, he made an impact not through hockey, but through the sheer force of his personality. “Just the way he would show up for other people is what I’ll always remember,” said Whitney, ending his brief elegy.

Showing up. That is what Jimmy did, and still should be remembered for.