Senior Researches the Relationship Between Sea Turtles and Global Warming

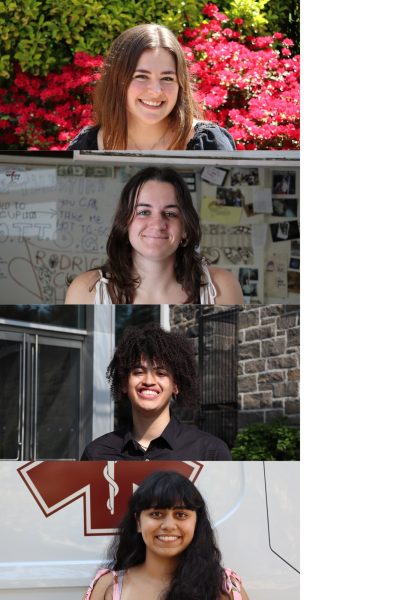

Lauren Staiger, FCRH ’22, is currently working on a pilot study for conservation efforts to learn how sea turtles react to global warming.

“An interesting thing about turtles is that in warmer temperatures, turtles only give birth to girls. With temperatures getting higher and higher you have more females than males being born, so there are no males to mate with. This research is important because it is helping open a window to see how species are adapting to global warming,” said Staiger.

Staiger works in a conservation lab under Evon Hekkala, Ph.D., looking at heat shock expressions in turtle shells. According to Staiger, heat shock proteins can be found in all organisms but are very important in reptiles and other animals that regulate their own body temperature. If a reptile such as a sea turtle gets too hot, heat shock proteins help lessen the harmful effects. Most heat shock protein research is done through live embryos using an invasive technique. Staiger’s research tests whether this same technique can be done in eggshells.

Staiger is creating an entirely new method to analyze the expressions of these heat shock proteins by using sea turtle eggshells rather than live embryos. The goal of the study is to discover if these genes are expressed in eggshells, and if she can amplify them enough to see them.

According to Staiger, her method has two major benefits. First, it is less invasive to test egg shells rather than live tissues from sea turtle hatchlings. Second, Staiger’s method also looks at heat shock proteins in the shells of sea turtles that did not hatch successfully. “In the invasive methods you’re only getting samples from successful hatchlings, so it would be a pretty cool breakthrough to see the difference between successful and unsuccessful hatchings and to cut back on invasive methods,” said Staiger.

So far, Staiger has found evidence that there is heat shock expression in eggshells. Staiger turned the RNA in preserved raw sea turtle eggshells into DNA then used PCR gels to amplify the gene expression in the DNA. These PCR gels make the DNA samples brighter when they have more expression. Staiger’s most recent sample came back with profound bright spots.

“We can visually see that there is something there. We found some expression but now we need to figure out what the expression is for and to analyze which eggshells showed that expression,” said Staiger.

Staiger said that the next step is to run quantitative PCR tests to compare the differences between genetic material in different DNA samples. This will give Staiger a better idea of the differences in expression between samples from eggshells of successful hatchings versus samples from eggshells of unsuccessful hatchlings. According to Staiger, this data could prove that the success of sea turtles hatching is based on how many heat shock proteins they produce.

“It would be a pretty big breakthrough to see how species are adapting to the warmer climate. It might help people care more about climate conservation efforts,” Staiger said.

Staiger got involved in this research after hearing about Hekkala’s lab from a friend. Staiger said that she felt like the research lab was a good fit because she studies biology and will be attending veterinary school in the fall. Furthermore, Staiger currently works for the Bronx Zoo as a veterinary technician assistant and previously worked in the New York Aquarium. Staiger said that she is passionate about animals, particularly sea life, and that she hopes to continue researching and working with animals.